I don’t know if Justice Terry Jennings is one of my Fivers, but apparently he agrees with a lot of Five Minute Law’s past propaganda regarding textualist application of the Texas Citizens Participation Act (TCPA).

In a concurring opinion issued just before Christmas 2018, Justice Jennings criticized the Texas Supreme Court’s overly broad and literal interpretation of the TCPA, urging both the legislature and the Texas Supreme Court to fix the problem. His opinion echoes some of the points I made in past hits like It’s Alive, It’s ALIVE! How to Kill a TCPA Motion in a Trade Secrets Lawsuit.

But what’s the problem? First let’s back up a little and recap:

- The TCPA was intended as an “anti-SLAPP” statute, i.e. to discourage a litigation bully from filing a lawsuit against a “little guy” in retaliation for the little guy exercising his free speech rights.

- When the TCPA applies, it gives the defendant the valuable procedural right to file a motion to dismiss that puts the burden on the plaintiff to support its claims with evidence, before the plaintiff has had any opportunity to take discovery.

- The TCPA applies when the plaintiff’s claim “is based on, relates to, or is in response to” the defendant’s exercise of the “right of free speech” or the “right of association.”

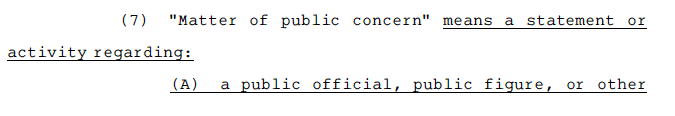

- The statute defines the “exercise of the right of free speech” broadly as a “communication made in connection with a matter of public concern,” with “matter of public concern” also defined broadly to include an issue related to “a good, product, or service in the marketplace.”[1]

- The statute defines the “exercise of the right of association” broadly as “a communication between individuals who join together to collectively express, promote, pursue, or defend common interests.”[2]

You can see from this language how the TCPA could lead to good results. A neighborhood group forms to stop a nearby refinery from releasing toxic gases. Global Oil Conglomerate instructs its BigLaw minions to sue the group for defamation based on posts on its Facebook page. Rather than buckling under the weight of enormous legal fees, the plucky neighborhood group hires a small town lawyer to file a TCPA motion to dismiss. The judge grants the motion, orders Global to pay the group’s legal fees, and Matthew McConaughey wins an Oscar for his portrayal of the lawyer.

Everyone’s happy. Alright, alright, alright.

But you can also see how the broad language of the TCPA could apply to lawsuits the legislature never had in mind. Imagine a porn star sues the President for defamation. The judge dismisses the case and orders the porn star to pay the President’s legal fees. It could happen.

That was at least a defamation case, which is clearly the type of case the legislature had in mind when it passed the TCPA. It seems much less likely that the legislature intended to fundamentally change the way departing employee cases are litigated.

Departing employee litigation is near and dear to my heart because it’s the kind of lawsuit I often handle. This is the type of case where an employee or group of employees leaves a company and either forms a competing company or goes to work for a competitor. Usually the first company asserts claims like breach of a non-compete and misappropriation of trade secrets.

These cases usually don’t raise any true “free speech” or “free association” issues. The “right of association” is not a defense to enforcement of a non-compete (provided the non-compete is reasonable and enforceable), and there is no First Amendment right to communicate your employer’s trade secrets to a competitor.

So what should the judge do in a departing employee case where the defendant files a TCPA motion to dismiss? On the one hand, the TCPA applies when a claim is based on “a communication between individuals who join together to collectively express, promote, pursue, or defend common interests.” Construed literally, that language applies to the allegation that an employee joined a competitor and disclosed his former company’s trade secrets.

On the other hand, the purpose of the statute is to protect constitutional rights, and a claim of trade secret misappropriation really doesn’t implicate such rights. Should the judge apply the statute literally, even though the result is not what the legislature intended?

Enter textualism.

We are all textualists now

Textualism is somewhat controversial. In part this is because in practice textualism is popular with one particular political party and ideology. But everyone who works in the law—at least everyone who is serious—is a textualist to some extent. No one seriously argues that the text of a statute—or a Constitution—should be ignored.

The fact that we are all textualists to some extent is apparent in the absence of any real “-ism” that is the opposite of “textualism.” No group identifies itself as the “Non-Textualists” or the “Anti-Textualists.” (The same point applies to “originalism,” but I won’t open that can of worms here.)

No, we all agree that when you interpret a text, the starting point is, duh, the text. You might find some radical academic types who question that premise, but no one who works in the law would seriously say “the text of the statute is totally irrelevant to me.”

On the other side of the spectrum, even the most committed textualist will concede that sometimes a judge should look to extrinsic sources to interpret the text. For example, if a statute is ambiguous, even after applying canons of statutory construction, then just about everyone would agree you can look to the purpose of the statute, or some other extrinsic source, to decide which of two reasonable constructions of the statute makes more sense.

Similarly, even the strict textualist camp would concede the principle—recognized in many court decisions—that extrinsic sources should be consulted when the literal application of a statute would produce a truly absurd result.

So if we all agree on these basic principles, what’s all the controversy about?

Here’s where it gets hard: when literal application of a statute would produce a result that, while not rising to the level of absurd, is contrary to the intended purpose of the statute. That’s where I think the dividing line is.

In this scenario, the true textualist bites the bullet and says “no, the judge should not look outside the text of the statute just because the result doesn’t make sense to the judge.”[3]

This is where textualism loses me, and I’m not the only one. When the literal application of a statute would produce a result at odds with the intended purpose of a statute, I tend to side with the non-textualists who say “no, in this case we’re not going to apply the literal meaning of the statute.” As I’ve written before, following the literal text in this situation “thwarts the intent of the legislature in the name of deference to the legislature.” See A SLAPP in the Face to Texas Trade Secrets Lawsuits – Part 2.

And I’ll give you a good example: application of the TCPA to departing employee litigation.

Application of the TCPA to departing employee litigation

Step one was the Texas Supreme Court holding in Coleman that the plain meaning of the TCPA’s broad definitions must be applied.[4] The Texas Supreme Court reaffirmed this plain meaning approach in Adams.[5]

Step two was the Austin Court of Appeals holding in Elite Auto Body that the TCPA applies to a claim that a departing employee disclosed trade secrets to his new employer. The court reasoned that a literal reading of the statute’s definition of “communication” would clearly include alleged communications among the departing employees and their new enterprise through which they allegedly shared or used the confidential information at issue.[6]

Elite Auto Body acknowledged that it would be reasonable to limit the statute to its stated purpose of protecting constitutional rights, but it found that argument foreclosed by Coleman’s plain meaning approach.[7]

One more note about Elite Auto Body: the court did not address the argument that the claims fell under the TCPA’s “commercial speech” exemption because it found that issue had been waived.[8] More about this exemption later.

Application of the TCPA to departing employee cases has since expanded. In Craig v. Tejas Promotions, the Austin Court of Appeals held that the TCPA applies to a claim of conspiracy to misappropriate trade secrets. The court reasoned that the claim rested on allegations that included “communications” between the alleged co-conspirators.[9]

In Morgan v. Clements Fluids, the Tyler Court of Appeals held that the TCPA applies to a claim based on departing employees’ communications among themselves and within the competitors, through which they share or utilize the alleged trade secrets.[10]

And that brings us to Gaskamp.

Gaskamp applies the TCPA to departing employee claims

In Gaskamp v. WSP, the WSP companies sued a group of former employees for allegedly starting a competing company while employed by WSP and then taking WSP’s trade secrets to the new company. WSP alleged that the former employees violated the Texas Uniform Trade Secrets Act (TUTSA) by using and disclosing WSP’s trade secrets, including proprietary design software used to create architectural designs.[11]

WSP argued that the TCPA did not apply. First, WSP said its lawsuit was based on theft and use of its trade secrets, not the employee’s right to freely associate or right of free speech as required by the TCPA. Second, WSP argued that the TCPA’s commercial-speech exemption applied.

The Court of Appeals rejected the first argument. The court cited WSP’s allegations that the employees used and disclosed WSP’s trade secrets to establish a competing engineering firm called Infinity MEP. The court reasoned that the alleged “transfer and disclosure” of WSP’s trade secrets to Infinity MEP “required a communication.” In addition, the allegation of inducing customers to reduce their business with WSP would “necessarily involve communications as defined by the TCPA.” And the allegation that the employees conspired among themselves to misappropriate trade secrets and interfere with WSP’s business also necessarily involved a communication.[12]

“All these communications were made by individuals who ‘join[ed] together to collectively express, promote, pursue, or defend common interests,” the court said, “the common interest being the business of Infinity MEP, operating as WSP’s competitor.” The alleged interference with customers involved communication “made in connection with a matter of public concern.” Thus, the claims related to the employees’ exercise of their rights of association and free speech, respectively, as broadly defined by the TCPA.[13]

This part of Gaskamp is important because the same reasoning would apply in almost any suit against departing employees that involves misappropriation of trade secrets. A plaintiff might be able to avoid this part of Gaskamp by alleging use of the trade secrets without any allegation of disclosure or communication of the trade secrets, but even in that case the employee could argue that the allegation necessarily relates to communications with the customers. The argument that the TCPA does not apply to trade secret misappropriation seems unlikely to succeed.

But the second argument in Gaskamp may be more promising for plaintiffs in departing employee cases. WSP argued that the statute’s commercial-speech exemption applied. That exemption states that the TCPA does not apply to a suit against “a person primarily engaged in the business of selling or leasing goods or services, if the statement or conduct arises out of the sale or lease of goods, services, or an insurance product, insurance services, or a commercial transaction in which the intended audience is an actual or potential buyer or customer.”

The Court of Appeals agreed with this argument (although for narrow procedural reasons).[14] Thus, the commercial-speech exemption applied, and the trial court was correct to deny the employees’ motion to dismiss under the TCPA as to two of the WSP plaintiffs.

This was no consolation for a third WSP plaintiff that failed to file a response to the TCPA motion (believing it had already been non-suited from the case). As to that entity, the Court of Appeals held that the motion to dismiss should have been granted.[15]

But at least one justice thought this result was “manifestly unjust.”

Justice Jennings questions the “textualist” approach to the TCPA

Justice Jennings wrote a concurring opinion. He joined in the majority opinion but wrote separately “to warn of the inherent dangers to Texas Jurisprudence posed by a rigid adherence to the ideological doctrine of so-called ‘textualism’ in construing our Constitution and statutes.”[16]

By applying the literal text of the TCPA’s definitions without considering the purpose of the statute, Justice Jennings said, the Texas Supreme Court has interpreted the TCPA “much more broadly than the Texas Legislature ever intended.” Applying the Texas Supreme Court’s literal interpretation of the statutes definitions necessarily led to a “manifestly unjust and absurd result,” but he and his colleagues were required to apply the definitions as instructed by the higher court.[17]

Still, Justice Jennings wanted to make his own view clear:

I respectfully disagree with the Texas Supreme Court’s unnecessarily broad interpretation and application of the TCPA to matters that exceed its expressly stated purpose to protect only the constitutional rights of free speech, to petition, and of association. A reasonable interpretation of the TCPA, when read in its entirety, reveals that it was never intended to apply to any of the claims at issue in this case. It should go without saying that communications allegedly made in furtherance of a conspiracy to commit theft of trade secrets and breaches of fiduciary duties do not implicate “citizen participation.”[18]

Justice Jennings went on cite the statute’s stated purpose “to encourage and safeguard the constitutional rights of persons to petition, speak freely, associate freely, and otherwise participate in government,” language indicating “the legislature intended to protect only constitutionally-protected freedoms that rise to such a level that they can be considered participation in government.”[19]

He acknowledged that the statute’s “awkward” definitions, standing alone, appear to include communications that are not constitutionally protected but said “we cannot read these definitions in isolation.” While the plain meaning is the best expression of legislative intent, that is not the case when “a different meaning is apparent from the context or the plain meaning leads to absurd or nonsensical results.”[20]

In Justice Jennings’ view, the broad definitions in the TCPA should be limited by the statute’s expressly-stated purpose of safeguarding constitutional rights. “Here, unfortunately, the Texas Supreme Court, in construing the TCPA by focusing like a laser on the literalness of the bare words of its pertinent definitions, has effectively strangled the real meaning and purpose of the statute.”[21]

But again, Justice Jennings was careful to concede that the Court of Appeals is bound by the decisions of the Texas Supreme Court. That’s why he wrote a concurring opinion rather than a dissent.

So what is to be done? Justice Jennings urged two potential solutions: (1) the legislature should revise the TCPA’s definitions to include qualifying language repeating the stated purpose of the TCPA to protect constitutional rights, and (2) the Texas Supreme Court should “revisit and correct is overly-broad interpretation of the TCPA.”[22]

Those sound like reasonable suggestions. But convincing the Texas Supreme Court to change its approach sounds like an uphill battle. And the legislature? Who knows. I’m not sure there’s any powerful interest group that has enough of a stake in reigning in the TCPA. Maybe business groups who want to make it easier to protect trade secrets and stop employees from competing?

But in the meantime, as we’ve already seen, the Gaskamp opinion suggest a simpler way to limit the application of the TCPA to departing employee litigation.

A textualist solution to the TCPA problem?

The solution I have in mind is right out of Shakespeare. The Merchant of Venice teaches us that when the bad guy goes textualist, the way to beat him is to go hyper-textualist. When Shylock insists on enforcing the plain meaning of a “pound of flesh,” Portia responds that his contract means exactly a pound—no more, no less. And only a pound of “flesh”—nothing else.

The commercial-speech exemption applied in Gaskamp could offer plaintiffs in departing employee cases a similar way out of the TCPA. The exemption applies when the defendant’s “statement or conduct” arises out of the sale or lease of goods or services.

What if we apply that definition literally? One could argue that a departing employee’s use or disclosure of the employer’s trade secrets always arises from the sale or lease of goods or services. What the TCPA giveth as “communication,” it taketh away as “commercial speech.”

Maybe that could work. But strangely enough, the Texas Supreme Court has not construed the commercial speech exception literally, instead adopting a four-part test based on the “context” of the exemption. See Castleman v. Internet Money Ltd., 546 S.W.3d 684, 688 (Tex. 2018).

What’s up with that?

*Update: The Dallas Court of Appeals later rejected a literal application of the TCPA and held that an element of public participation is required. See Metroplex Courts Push Back on Broad Application of the TCPA. Then the legislature and the Fifth Circuit carved back the TPCA even more. See how the story ends at Shrinkage: TX Legislature and 5th Circuit Cut the TCPA Down to Size.

_____________________

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

[1] Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code § 27.001(3), (7).

[2] Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code § 27.001(2).

[3] The realists—another camp!—might question how many “textualists” actually do this in practice when applying the literal text would yield a result they don’t like. But in theory this is what the true textualist is supposed to do.

[4] ExxonMobil Pipeline Co. v. Coleman, 512 S.W.3d 895, 901 (Tex. 2017).

[5] Adams v. Starside Custom Builders, LLC, 547 S.W.3d 890, 894-97 (Tex. 2018).

[6] Elite Auto Body LLC v. Autocraft Boywerks, Inc., 520 S.W.3d 191, 205 (Tex. App.—Austin 2017, pet dism’d).

[7] Id. at 204.

[8] Id. at 206 n.75.

[9] Craig v. Tejas Promotions, LLC, 550 S.W.3d 287, 296-97 (Tex. App.—Austin 2018, pet. filed). See also Grant v. Pivot Tech. Solutions, Ltd., 556 S.W.3d 865, 881 (Tex. App.–Austin 2018, pet. filed) (TCPA applied to claims similar to those in Elite Auto Body based on hiring of competitor’s employees and alleged sharing and use of confidential information).

[10] Morgan v. Clements Fluids South Texas, Ltd., No. 12-18-00055-CV 2018 WL 5796994, at *3 (Tex. App.—Tyler Nov. 5, 2018, no pet. h.).

[11] Gaskamp v. WSP USA, Inc., No. 01-18-00079-CV, at *1-3 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] Dec. 20, 2018).

[12] Id. at *11.

[13] Id. at *12 (citing Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code §§ 27.001(2), (3), 27.003(a)).

[14] Id. at *9.

[15] Id. at *13.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Id. at *14 (citation omitted).

[19] Id.

[20] Id. at *15 (citing Molinet v. Kimbrell, 356 S.W.3d 407, 411 (Tex. 2011)).

[21] Id. at *16.

[22] Id.

Leave a Comment