Before we get into copyright infringement, first let me do you a favor. If you haven’t watched the video of Weird Al Yankovic’s “Word Crimes,” you have to check it out on YouTube. Weird Al has been churning out great song parodies since the 80s, but Word Crimes may be his magnum opus. It’s so good.

Word Crimes is a parody of “Blurred Lines,” a song by Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams that generated controversy from the start.

First there was the music video, which was a little, uh . . . PG-13?

Then people started scrutinizing the cringey lyrics.

And all of that was before the famous (or infamous?) Miley Cyrus performance with Thicke at the 2013 MTV Video Music Awards.

It was all fun and games until the copyright lawsuit. The estate of Marvin Gaye sued Thicke and Williams, claiming that Blurred Lines infringed the copyright in Gaye’s 1970s classic “Got To Give It Up.”

Williams v. Gaye and other “This Song Sounds Like That Song” Lawsuits

Gaye’s estate eventually won a judgment for over $4.8 million in damages plus a running 50% royalty on future revenues, and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the judgment in Williams v. Gaye, 895 F.3d 1106 (9th Cir. 2018).

That case was of course just the latest in a long line of “this song sounds like that song” copyright lawsuits.

In the 1970s, the Chiffons claimed that George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord” copied their hit song “He’s So Fine.” (For my younger readers, George Harrison was in a band called the Beatles that was big in the 1960s.)

In the 1980s, Huey Lewis and the News got upset when they heard Ray Parker Jr.’s “Ghostbusters.” They thought the groove sounded a little too familiar, like the one in their song “I Want a New Drug.”

Who ya gonna call? Your Lawyer!

YouTubers Assemble! The Dua Lipa Lawsuit

And the tradition continues today. If you still pay any attention to the pop charts, you probably know the 2020 release “Levitating” by Dua Lipa. Honestly, as a GenXer I didn’t even know who she was until the 2021 Grammy nominations, but then I checked out her album Future Nostalgia, and I gotta say, it’s pretty dang good.

But at least one band didn’t jump on the Dua Lipa bandwagon. Artikal Sound System, a South Florida reggae band, filed a lawsuit claiming that “Levitating” copied their 2017 song “Live Your Life.”

You don’t need to know anything about music theory to hear that the chorus in Levitating sounds an awful lot like the chorus in Live Your Life.

YouTube music theorist Adam Neely breaks it down in his video Did Dua Lipa ACTUALLY plagiarize Levitating? Rick Beato has a similar video Dua Lipa vs Reggae Band Lawsuit: Let’s Compare!

And if you are really a YouTube music theory nerd, you can watch Neely and Beato talking with each other about the Levitating controversy here.

As they both point out, the choruses in Levitating and Live Your Life have almost identical melody, rhythm, and chord changes.

But is that copyright infringement? Most people will form a pretty quick opinion on that question after hearing the two choruses in question, regardless of what the law says. But people with even a passing interest in copyright law probably want to know how similar the two songs have to be.

The answer is simple: substantially similar. There you have it. Mystery solved.

Understanding the “Substantially Similar” Standard

I’m kidding, of course. “Substantially similar” is the crucial legal standard in a copyright lawsuit, but knowing that in the abstract tells you almost nothing about how a “this song sounds like that song” copyright lawsuit will come out.

To understand how “substantially similar” works in practice, you need to know a little bit about substantive copyright law, a little bit about litigation procedure, and a little bit about music theory.

Fortunately, in each case I know just enough to be dangerous. I don’t necessarily specialize in copyright law, but I have been a practicing litigator in Texas for almost 25 years, I’ve worked on copyright litigation before, and I know the basics of copyright law. I even wrote a blog post about it: The Originality Requirement in Copyright Law.

Same with music. I have never played music professionally and don’t have any kind of music degree, but I play several instruments, I have an intermediate understanding of music theory, and as I’ll explain later, you don’t need much more than a basic understanding of music theory to understand the typical pop song copyright lawsuit.

From my experience with both litigation and music, I can tell you the bottom line is this: the really important question in a “this song sounds like that song” lawsuit is not “how similar is substantially similar?” but who decides how similar is substantially similar, the judge or the jury?

And for all the other blog posts and explainer videos out there, I think this is a question that doesn’t get enough attention.

Let’s break it down.

Copyright Law Basics

At the most fundamental level, copyright law protects original works of expression. That means things like songs, novels, movies, paintings, sculptures, poems, TikTok videos. You get the idea.

Keep in mind, copyright does not protect ideas. That’s the realm of patent law. Copyright protects expression of ideas, not the ideas themselves. And if you can easily grasp that distinction, you’re a smarter cookie than me. But that is the distinction.

Patent and copyright are somewhat similar in the sense that a patent requires novelty, while copyright requires originality. A work of expression has to be sufficiently original to qualify for copyright protection.

But “original” in this context doesn’t mean what you might think of as original. A song, for example, doesn’t have to be “creative” in the sense of novel or innovative to be protected by copyright. And the originality requirement isn’t about passing aesthetic judgment. A song can be trite and uninteresting and still be sufficiently original for copyright purposes. It’s a low bar.

That means almost every song at issue in a “this song sounds like that song” lawsuit will clear the low bar for copyright “originality.” So originality really becomes a non-issue in these lawsuits, right? Well . . . let’s come back to that later.

Let’s assume Song 1 is original enough to receive copyright protection. Song 2 sounds a lot like Song 1. Does Song 2 infringe Song 1’s copyright?

Proving Copyright Infringement

To prove copyright infringement, the owner of Song 1 has to prove two things:

- “Factual” copying

- “Substantial similarity”

These are two distinct, but overlapping, requirements.

Factual copying means the artist that created Song 2 copied it from Song 1. In theory, that’s a pretty simple issue. But in practice, it get complicated, for the simple reason that in most cases there is no direct evidence of copying.

By “direct” evidence, I mean evidence like the composer of Song 2 admitting he copied Song 1, or a witness testifying, “yeah, I was there in the studio that day when George started writing the song, and I remember him saying he wanted to write something that sounded just like He’s So Fine.”

Usually you don’t have that. The evidence of factual copying will usually be circumstantial, i.e. not eye-witness testimony.

Evidence and Procedure in Copyright Litigation

Enter the law of evidence and procedure. Courts have developed a framework for how to evaluate whether the plaintiff in the lawsuit has enough circumstantial evidence of factual copying. (I’m going to use the terminology from the Fifth Circuit, where I practice, but the frameworks from other circuits are similar.)

There are two ways to prove factual copying through circumstantial evidence.

First, you can prove factual copying by showing that the creator of Song 2 had access to Song 1, and that there is “probative” similarity between Song 2 and Song 1. Probative similarity is a lower level than “substantial similarity.” It means similarity that, “in the normal course of events, would not be expected to arise independently.”

The second way to prove factual copying is evidence of “striking” similarity. That’s where the similarities “are of a kind that can only be explained by copying, rather than by coincidence, independent creation, or prior common source.” Guzman v. Hacienda Records and Recording Studio, Inc., 808 F.3d 1031, 1039 (5th Cir. 2015). In other words, you don’t need evidence of access if the songs are so similar that a reasonable person could think there was factual copying based on the similarity alone.

So if you prove one of those two things, do you win on factual copying? Not so fast. These two options are just what gets you in the courthouse door. If you show the judge you have evidence of one of the two, that only means you get to submit the factual copying question to the jury. You still have to persuade them.

And you also have to prove substantial similarity. Remember, that’s the second element of copyright infringement.

Unlike the factual copying element, which involves evidence “extrinsic” to the two songs themselves, the substantially similar element focuses entirely on the two songs themselves. You might say substantial similarity is a purely “objective” or “intrinsic” element.

Substantial similarity is the most difficult copyright element to define. It is determined by a side-by-side comparison between the original and the copy to determine whether a layman would view the two works as “substantially similar.” Positive Black Talk, Inc. v. Cash Money Records, Inc., 394 F.3d 357, 374 (5th Cir. 2004).

But who does the side-by-side comparison, the judge or the jury? It depends.

Who Decides “Substantial Similarity”?

Substantial similarity is typically left to the factfinder, i.e. the jury in a jury trial, but summary judgment maybe appropriate if the judge, after viewing the evidence and drawing inferences in a manner most favorable to the plaintiff, finds that no reasonable juror could find substantial similarity. Gen. Univ. Sys., Inc. v. Lee, 379 F.3d 131, 142 (5th Cir. 2004).

As a practical matter, this means the plaintiff first has to persuade the trial court judge that there is enough “substantial similarity” to submit the question to the jury. In most cases, if it’s a close call at all, the trial court judge will let the plaintiff submit the question to the jury (for reasons).

Then, if the jury finds substantial similarity, the plaintiff has to persuade the trial court judge that there was sufficient evidence to support that finding, so that the trial court will enter judgment for the plaintiff. And then, the plaintiff has to persuade the appellate court there was enough evidence of substantial similarity to support the verdict and the judgment.

Already, some of you are probably thinking back to the originality requirement. We just can’t get away from it, because there’s no way to evaluate whether the similarity is “probative” or “striking” without getting into how original the similar elements are. For example, if the similarity is that both songs use a 12-bar blues chord progression, that’s not going to be probative or striking, because that’s such a common element.

Some Music Basics

To understand copyright lawsuits about music, I think it’s helpful to distinguish between two aspects of a musical performance. For convenience I’ll call them the “Sheet Music Elements” and the “Performance Elements.”

The Sheet Music Elements are the aspects of a recorded song that would typically be found in the “sheet music” version of the song you might buy at the typical music store. Those elements will include the notes of the melody, the rhythm of the melody, the underlying chords, and the lyrics. The Sheet Music Elements could also include non-lyrical elements like a distinctive piano intro or guitar riff, especially if it’s an identifiable element of the original performance.

The Sheet Music Elements are also the elements that you will typically see in the typical music theory explainer video, or in expert witness testimony (more about that later).

The Performance Elements are all the other elements of a recorded song, the parts that don’t get reflected in the sheet music. The instruments used, the tone of the instruments, the singer’s voice and style, the timbre of the voices and instruments, things like that. These elements don’t get enough attention. I would venture to say they are the crucial elements that make the difference between a song that is just ok and a classic.

And when you combine great Sheet Music Elements with great Performance Elements, you really start cooking. See The Beatles, supra.

The Sheet Music Elements tend to get disproportionate attention in copyright litigation. It probably reflects a certain bias towards the Western European musical tradition, passed down through the Tin Pan Alley tradition of American popular music, but I’ll leave that can of worm for musicologists who are smarter about such things.

For our purposes, it suffices to say that the Sheet Music Elements are usually the focus of the “substantially similar” issue in copyright litigation.

Enter the music expert in copyright litigation.

Music Experts in Copyright Litigation

Reading about expert witnesses in copyright always makes me chuckle. The thing that’s funny to me is that you don’t need to be much of an expert to understand the musical issues in a typical “this song sounds like that song” lawsuit. The musical elements at issue are usually not complicated.

For this reason, anyone who took a few years of piano lessons as a kid or played in the high school band, or whatever, is going to know enough about music theory to understand the musical elements at issue. A Ph.D in musicology is not required.

But of course, when there’s a lot of money at stake, lawyers are gonna hire expensive experts.

Serving as a music expert in a copyright infringement case is a pretty sweet gig. If you’re the plaintiff’s expert, the assignment is pretty simple. You just do a side-by-side comparison of the musical elements of the two songs that are the same, or similar, and maybe prepare some music notation or other graphics to show the comparison.

And it’s usually going to be pretty easy to show the elements of the two songs that are the same or similar.

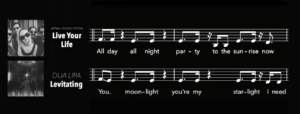

For example, here’s YouTuber Adam Neely’s notation showing that the melody and rhythm of Dua Lipa’s “Levitating” is pretty darn similar to that of Artikal Sound System’s “Live Your Life”:

Serving as the defense expert is a little more complicated, but not much. If you’re the defense expert, first you’re going to point out the elements of the two songs that are not the same. That’s usually not hard.

But then if you’re lucky, you get to do something as the defense expert that is more fun: find a song that pre-dates both songs at issue that also has the common elements of those two songs.

Not gonna lie, I love this move.

Adam Neely pulled this off in his video about the Dua Lipa lawsuit. After showing that the melodies in “Levitating” and “Live Your Life” have pretty much the same notes and rhythm, Neely points out that the same notes and rhythm are also found in the song “Rosa Parks” by Outkast:

And guess what? The Outkast song came out almost 20 years before “Live Your Life.”

The thing I Iove about this move is that it shows how little is really new under the sun, at least when it comes to popular music. I think that’s something musicians and songwriters might appreciate a little more than the casual music listener.

It’s effective because it’s not enough to show the two songs have similar elements. The plaintiff needs to show substantial similarity with the original, protectable elements of the song. Remember the originality requirement covered earlier?

This sets up a classic “battle of the experts,” which is common to all kinds of litigation, not just copyright lawsuits. The plaintiff’s expert will say the two songs are substantially similar. The defense expert will say they’re not.

So who decides which expert is right?

That brings me back to the “Blurred Lines” case.

Can You Copyright a Musical Style?

It was the jury, not the judge, that decided “Blurred Lines” was substantially similar to “Got To Give It Up.” And in a 2-1 decision, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals said there was enough evidence to support the jury’s verdict, even if we think they got it wrong.

And let me just put my cards on the table: they got it wrong.

Sure, the two songs have a similar style. That’s obvious, and not surprising, considering Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke acknowledged that “Got To Give It Up” provided inspiration for “Blurred Lines.”

But you can’t copyright a “groove” or a “style,” especially when it uses elements that are common to dozens, if not hundreds, of other songs. I agree with dissenting Justice Jacqueline Nguyen: “The majority allows the Gayes to accomplish what no one has before: copyright a musical style.”

“Blurred Lines” and “Got To Give It Up” are not objectively similar, she wrote. “They differ in melody, harmony, and rhythm,” she said. “Yet by refusing to compare the two works, the majority establishes a dangerous precedent that strikes a devastating blow to future musicians and composers everywhere.”

Justice Nguyen criticized the plaintiffs musicologist expert, Finell, for “cherry-picking” snippets of the two songs that were similar. And she said the case did not present a typical battle of experts for the jury to decide:

The majority, like the district court, presents this case as a battle of the experts in which the jury simply credited one expert’s factual assertions over another’s. To the contrary, there were no material factual disputes at trial. Finell testified about certain similarities between the deposit copy of the “Got to Give It Up” lead sheet and “Blurred Lines.” Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke don’t contest the existence of these similarities. Rather, they argue that these similarities are insufficient to support a finding of substantial similarity as a matter of law. The majority fails to engage with this argument.

The dissenting opinion then methodically reviewed the alleged similarities and showed that the similar elements were just too commonplace in music to be protectable. For example, the first measure of the signature phrase in both songs begins with a rhythm of six eighth notes. But “[a] bare rhythmic pattern, particularly one so short and common, isn’t protectable.”

The Importance of Procedure in Copyright Litigation, or Any Litigation

The majority opinion in Williams v. Gaye didn’t really engage with these arguments. Instead, the majority focused on procedure. It narrowly held that there was evidence to support the jury’s verdict, even if the jury might have gotten it wrong.

The majority criticized the dissent for not paying enough attention to procedure. “The dissent’s position violates every controlling procedural rule involved in this case,” it said.

It was wrong for the dissent to weigh the strength of the testimony by the two dueling music experts, the majority said. “We decline the dissent’s invitation to invade the province of the jury: Applying the proper standard of review, one simply cannot say truthfully that there was an absolute absence of evidence supporting the jury’s verdict in this case.”

Williams v. Gaye is therefore a great lesson in the importance of procedure in copyright litigation, or any litigation, really.

The defense lawyer can have great arguments that the two songs are not substantially similar. But if the plaintiff’s lawyer has enough evidence to get the question to a jury, and if the jury finds for the plaintiff, it will usually be very difficult for the defense to get the verdict overturned on appeal. And if the defense lawyer doesn’t make the right procedural motions in the trial court, the court of appeals may find those arguments were waived for appeal.

The danger, I think, is that the jury may decide the substantial similarity issue based on extrinsic factors, rather than an objective comparison of the two songs. Which artist does the jury like or respect more? Which side’s lawyer is more likeable? Does the plaintiff’s widow seem sympathetic?

I suspect maybe, just maybe, the jury in Williams v. Gaye liked Marvin Gaye better than Robin Thicke.

Any seasoned trial lawyer will tell you things like that make a difference to the jury. But is that really how we want these cases decided?

____________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

Leave a Comment