On April 9, 2021, Taylor Swift released the album Fearless (Taylor’s Version), her re-recording of her second album, originally released in 2008 when she was 18.

This was a big deal. I’m not really a huge Taylor Swift fan, but she’s undeniably talented, and my daughter was seven when the original Fearless album came out. So you do the math.

I also love the fact that the origin story of Fearless (Taylor’s Version) is found in the nuances of U.S. copyright law. If you want to understand why, check out this excellent lawsplainer thread from law school student “Mauv” on Twitter.

I can’t improve much on Mauv’s explanation, but it got me thinking about the originality requirement in copyright law, an issue I sometimes grapple with in my law practice. It’s a requirement that is easy to explain in theory, but often difficult to apply in practice, as we will see.

Copyright law protects original works of expression. We’re talking stuff like movies, artwork, sculpture, novels, musical compositions, poetry, and yes, recordings of pop songs.

This is not to be confused with trademark law, which protects source identifiers for goods or services—usually a word, short phrase, or logo. A trademark doesn’t have to be original or creative to function as a trademark; it just needs to create an association in consumer minds between a product or service and its source.

Copyright law, in contrast, is about protecting creativity. The copyright owner must create an original work of expression.

The originality requirement in copyright law

This doesn’t require any evaluation of artistic merit, which would be pretty subjective. And original doesn’t necessarily mean novel. As the U.S. Supreme Court held, the originality requirement “means only that the work was independently created by the author (as opposed to copied from other works), and that it possesses at least some minimal degree of creativity.” Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340 (1991).

That’s a good thing for creators, because you could make a case that there’s nothing really new under the sun, especially in music. Did Beethoven invent the simple melody in Ode to Joy? Copland the folk melody featured in Appalachian Spring? Even the great Stevie Ray Vaughan borrowed plenty of blues guitar licks from Albert King.

You can always identify components of music taken from previous works. Most of the songs on Fearless, for example, use the same four chords as hundreds of other pop, rock, or country songs. And lyrically, Taylor wasn’t exactly breaking new ground: girl meets boy, boy lets down girl, girl grows up a little.

But you put those old musical cliches together in a new way, and that’s where the magic happens. There’s no question a Taylor Swift song meets the originality requirement.

At the other end of the spectrum, consider the old White Pages. It was basically just an alphabetical list of names and phone numbers. Sure, the author had to make some choices, like what typeface to use, how many columns, etc. But courts said we have to draw the line somewhere. So regardless of how much work may go into it, a utilitarian document like a phone book typically won’t meet the originality requirement.

A slightly harder case is a cookbook. The problem with claiming a copyright for a recipe is that you really can’t separate the idea of the recipe—the ingredients, quantities, how you prepare it—from the expression of that idea. And copyright law protects expression, not ideas.

So courts have said a recipe book will only receive copyright protection when it includes additional creative elements, like a story about how your grandmother used to bake these cookies when you were a child.

These are relatively easy cases. An original song is sufficiently creative, even if it uses elements from other songs. A list of phone numbers isn’t.

But there are other categories that fall somewhere in the middle. Take jewelry designs, for example.

The originality requirement applied to jewelry design

This has been an issue for a long time. In the Trifari case from 1955, the defendant claimed that the plaintiff’s article of lady’s costume jewelry was “devoid of originality” because many firms had previously made similar “cab” necklaces.

But the court rejected this argument, and in doing so stated a standard for originality of jewelry designs that applies to this day:

It is not the idea of the use of the cab which is the subject of the copyright but rather the author’s artistic expression which reflects a distinguishable variation from what had gone before. The copyrighted matter need not be strikingly unique or novel. All that is needed is that the author contribute more than a merely trivial variation, something recognizably his own

Trifari, Krussman & Fishel, Inc. v. Charel Co., 134 F. Supp. 551, 553 (S.D.N.Y. 1955).

So that takes care of the originality requirement for jewelry designs. We know the standard. All we have to do is apply it.

But of course, stating the standard is the easy part. Applying the standard is the hard part.

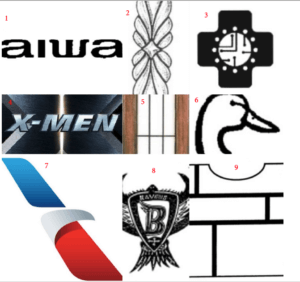

If you think it’s easy, take a look at these examples and, just for fun, make a list of the ones you think contain a sufficient spark of creativity to meet the originality requirement of copyright law.

How many did you get? The correct answer is five. Specifically, nos. 1, 2, 3, 5, and 8 are sufficiently creative. The other four are not.

If you’re saying yeah, well that’s just your opinion, man. Well, ok, but I have cites:

Yurman Design, Inc. v. PAJ, Inc., 262 F.3d 101 (2d Cir. 2001) (No. 1); Jane Envy, LLC v. Infinite Classic Inc., 2016 WL 797612 (W.D. Tex. Feb. 26, 2016 (Nos. 2, 4, and 6); Tacori Enterprises v. Beverly Jewelry Co. Ltd., 2008 WL 11338681 (C.D. Cal. Aug. 20, 2008) (No. 3);Van Cleef & Arpels Logistics, S.A. v. Landau Jewelry, 547 F. Supp. 2d 356 (S.D.N.Y. 2008) (No. 5); Protecting the Intellectual Property of Jewelry Designs (2018) (No. 7); Merit Diamond Corp. v. Frederick Goldman, Inc., 376 F. Supp. 2d 517 (S.D.N.Y. 2005) (No. 8); Todd v. Montana Silversmiths, Inc., 379 F.Supp.2d 1110 (D. Colo. 2005) (No. 9).

You cannot argue with the courts.

But seriously, of course these examples present close calls. Other judges could have easily ruled differently.

You might almost think that copyright law requires judges to draw lines that can seem arbitrary, but that this is an inherent problem, and perhaps one presented by every area of law.

And if you think these jewelry designs present close calls, wait until you consider copyright for distinctive logos.

The originality requirement applied to logos

Logos are right at the border between copyright law and trademark law. Consider this well-known logo:

There’s no question this logo functions as a trademark. Just about anyone in the U.S. knows that logo means American Airlines. But is that “AA” logo creative enough to warrant copyright protection?

Probably not. According to the U.S. government, these are some examples of works not subject to copyright: “Words and short phrases such as names, titles, and slogans; familiar symbols or designs; mere variations of typographic ornamentation, lettering or coloring.” 37 C.F.R. § 202.1(a).

Still, some logos could be sufficiently creative to be more than “mere variations” of typographic, ornamentation, lettering, or coloring.

Here are some real-world logos for which companies sought copyright protection. If you’re scoring at home, make a list of which ones you think are original enough to warrant copyright protection:

How many are on your list? In this case, the correct answer is all of the above.

Surprised? Embarrassed you got it wrong?

Just shake it off.

_______________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation (and sometimes copyright litigation) at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

Leave a Comment