Checking in on our favorite non-compete fact pattern

You might be wondering what happened to our friend Dawn Davis.

Well, with the housing market booming, the window business is doing well. Dawn just had her best year of sales at Paula Payne Windows. But Dawn felt like she wasn’t getting a big enough cut of the profits. So she jumped ship and went to work for Real Cheap Windows.

Trouble is, Dawn had a two-year non-compete with Payne, and Payne sued, asking for an injunction and damages. The judge denied the injunction, but the case is about to go to trial on the damages. Dawn admits violating the non-compete, as written, but has other defenses.

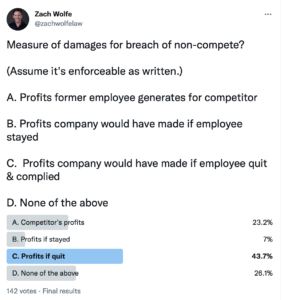

So what is the proper measure of damages for Dawn’s breach of a non-compete?

Multiple choice test on non-compete damages

Before you give your answer, let me clear away some brush so we can simplify.

First, assume we’re talking about Texas law, because that’s where I practice. (The law in other states isn’t likely to be fundamentally different on this point.)

Second, assume Dawn’s non-compete is enforceable as written. (A big assumption, granted, but we’re trying to keep this simple.)

Third, assume the non-compete does not have a liquidated damages clause, i.e. a provision where Dawn and Paula Payne Windows agree in advance on an amount of damages for a breach.

Fourth, assume Dawn’s employment was at-will, so she could leave any time for any reason.

Fifth, assume the trial date is within the two-year term of the non-compete.

Ok, with those potential complications out of the way, here are your choices. The proper measure of past damages for Dawn’s breach of the non-compete is:

A. The net profits Dawn would have generated for Real Cheap Windows to date if she had stayed there.

B. The net profits Dawn’s sales have generated for Real Cheap Windows since Dawn left Paula Payne Windows.

C. The net profits Real Cheap Windows would have made from sales to Dawn’s customers if Dawn had quit and complied with her non-compete.

D. None of the above.

Ok, make your choice and write it down.

But make sure it’s net profits

Notice that in Choices A, B, and C, I said “net profits,” not gross revenues or gross profits. Texas law is clear that evidence of net profits is required, as I explained in Nothing But Net: Gross Profits Are Not Lost Profits Damages Under Texas Law.

As that post explains, this net profits issue is thornier than it sounds, so let’s set it aside for now and assume for purposes of this discussion that Paula Payne Windows has offered proper evidence of net profits, i.e. deducting all expenses that should be deducted.

Also, you might have noticed I said “past” damages. Future damages opens another can of worms.

Did you get the right answer?

So what’s your answer? If you said C, you agree with Five Minute Law. But D is also a respectable answer, and you could even make a case for B.

Choice A is just wrong. But don’t feel bad, a lot of people make this mistake, even experienced litigators.

The problem with Choice A is that we don’t have indentured servitude in this country. Remember, I said the employment was at will. Dawn was free to leave at any time.

Also, pulling up to 30,000 feet above for just a second, let’s keep in mind that we are talking contract damages.

Yes, I know, often in such cases there are other causes of action. Breach of fiduciary duty and misappropriation of trade secrets are two of the usual suspects. But right now we are only talking about damages for the breach of contract claim.

Two things to keep in mind about breach of contract damages.

Contract damages generally

First, the purpose of contract damages is to compensate, not to punish. This is a fundamental distinction in the Anglo-American legal tradition. Tort damages can be used to punish (sometimes). But we usually don’t do that in contract damages.

No, contract law tends to be amoral. It’s the law of the marketplace. It’s not about punishing someone for breaking a promise, it’s about promoting efficiency and honoring reasonable expectations.

This amoral ethos gives rise to the “efficient breach” theory. That’s the idea that there’s nothing necessarily wrong with breaking a contract, as long as the party that breaks it compensates the other party for the breach.

The second thing about contract damages, related to the first, is that the usual measure of damages is the “expectation interest” of the non-breaching party. The purpose of the damages is to put the non-breaching party in the same financial position it expected to be in if the other party had performed the contract.

Back to the hypo

Now that you’re armed with those principles, you can probably see why Choice A is wrong. Dawn Davis broke the contract not by quitting her job at Paula Payne Windows, but by competing with Paula Payne Windows after she quit.

She had every right to quit. So the right question is, what financial position would Paula Payne be in if Dawn had quit but complied with the non-compete?

This also tells us why Choice B is not a strong choice, even if it has some intuitive appeal.

Choice B is the net profits Dawn’s sales have generated for Real Cheap Windows since Dawn left Paula Payne Windows.

I say this choice has some intuitive appeal, because there is a certain moral logic to it. If Dawn promises not to compete, and then she breaks that solemn vow by going to work for Real Cheap, isn’t it fair to make Real Cheap pay back the profits it makes off of Dawn’s breach? We can’t let Dawn get away with this, we have a society!

It is for this very reason (in part) that other causes of action, such as breach of fiduciary duty and misappropriation of trade secrets, might allow Paula Payne to recover the profits made by Real Cheap as a punishment for Dawn’s illicit conduct.

But not breach of contract! Remember, the purpose of contract damages is to compensate, not to punish.

Why Choice C is the best

If the purpose is to compensate, then we need to ask ourselves, what measure of damages would put Paula Payne Windows in the financial position it would have been in, had Dawn Davis complied with the non-compete?

That’s why the best answer to my question is C, the net profits Real Cheap Windows would have made from sales to Dawn’s customers if Dawn had quit and complied with her non-compete.

You can use various counter-factuals to formulate this measure of damages.

Suppose Dawn had quit and gone into a different line of work. Or suppose Dawn had quit and moved to another state outside the geographic scope of the non-compete. You could even hypothesize that Dawn quit and went to work for Real Cheap Windows, but didn’t take any customers with her and started selling to entirely new customers.

In each of those scenarios, Paula Payne Windows would have been in a better position to hold on to Dawn’s customers and make profits from the sales to those customers. And the profits Paula Payne Windows can prove it would have made are the proper measure of the damages for breach of the non-compete.

This seems relatively non-controversial to me.

Ah, but there are complications, of course. You can at least make a case for choices B and D.

The case for Choice B

Let’s go back to Choice B, the moralist’s choice.

There is some case law support for measuring Paula Payne’s lost profits by the profits Dawn generated for her subsequent employer, Real Cheap.

In some situations, the profits generated by an employee at the subsequent employer could be relevant to the previous employer’s actual lost profits.

When Employer B’s gain is Employer A’s loss

Suppose a dance instructor develops relationships with students while working for a dance studio. The dance instructor leaves the studio and joins a competing studio, in violation of her non-compete. Over 30 students follow the instructor from the first studio to the second studio. In that situation, evidence of the second studio’s profits could be relevant to determining the first studio’s lost profits, if there is evidence the first studio still had the capacity to service those students and would have done so if the instructor had not worked at the second studio. Those were the facts of Arabesque Studios, Inc. v. Academy of Fine Arts, Int’l, Inc., 529 S.W.2d 564, 569 (Tex. App.—Dallas 1975, no writ).

There were similar facts in Chandler v. Mastercraft Dental Corp., 739 S.W.2d 460 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth 1987, writ denied). In that case, Ross bought Mastercraft Dental from Chandler and Johnston. Id. at 462. Chandler and Johnson agreed to a five-year non-compete but helped form a competing business, Dayton Dental. Id. Chandler and Johnston had developed extensive customer relationships. Id. at 465. They referred customers to Dayton Dental after leaving Mastercraft, causing Mastercraft’s profits to decline. Id. at 466. Based on this evidence, it was not error for the trial court to include the profits of Dayton Dental as an element of damages for the jury to consider. Id.

These cases have something important in common: in both cases, the second employer’s gain was clearly the first employer’s loss. In other words, there was evidence that the first employer would have made the profits made by the second employer if the employees had not gone to work for the second employer and taken the customers with them.

So, in my view, this measure of damages should only be an alternative in the rare case where the first employer can show that its profits from the lost sales would have been the same as the second employer’s profits.

I’m not saying absolute certainty down to the penny is required. Lost profits damages must be proven with “reasonable certainty.” So if the first employer can prove its profits would have been approximately the same as the second employer’s profits, then evidence of the second employer’s profits might be used as a rough measure.

But again, this only works when the evidence shows the second employer’s gain was the first employer’s loss. That isn’t always true. For example, suppose Dawn Davis goes to work for Real Cheap Windows and sells to entirely new customers. Logically, the profits from those sales should only be included in the actual damages if Paula Payne Windows can show it would have made those sales otherwise.

And even then, the second employer’s profits are really just a proxy for the real thing we’re trying to measure, which is the profits the first employer would have made. That means Choice C is still superior to Choice B, in my opinion.

The unjust enrichment theory in tortious interference cases

There is also some case law support for Choice B when the cause of action is for tortious interference with contract, not just breach of contract, although that distinction is problematic, as I’ll explain momentarily.

In Sandare Chemical Co. v. WAKO International, Inc., 820 S.W.2d 21 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth 1991, no writ), the court held that the second employer’s profits can be recovered as unjust enrichment damages on a claim for tortious interference with contract, where the plaintiff cannot show with certainty the profits it would have made absent the interference, i.e. where the plaintiff’s own lost profit is not “readily ascertainable.” Id. at 24-25. The court mainly relied on non-Texas precedent.

Part of the rationale for this rule is that tortious interference is—you guessed it—a tort. And as we’ve seen, tort damages can be used not just to compensate, but to punish bad behavior.

Still, even for tortious interference, this rationale is problematic, as I warned. The Texas Supreme Court has said that the measure of damages for tortious interference with contract is the same as the measure of damages for the underlying breach of contract, meaning you can’t get damages for tortious interference with contract that you couldn’t get for the underlying breach of contract. See Am. Nat. Petroleum Co. v. Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line Corp., 798 S.W.2d 274, 278 (Tex. 1990) (“The basic measure of actual damages for tortious interference with contract is the same as the measure of damages for breach of the contract interfered with, to put the plaintiff in the same economic position he would have been in had the contract interfered with been actually performed”); Palla v. Bio-One, Inc., 424 S.W.3d 722, 726 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2014, no pet.) (same, citing American National Petroleum).

Sandare Chemical conflicts with that principle.

And now perhaps we’ve gotten too much in the weeds. The bottom line is that while you can make a case for Choice B, it remains inferior to Choice C. In my personal opinion.

The case for “none of the above”

There is also a case to be made for Choice D, none of the above. You could argue that Paula Payne Windows should get no damages, because it can’t prove it would have made all of those hypothetical sales to Dawn’s customers if Dawn left.

Let’s assume, as is often the case, that Dawn has strong personal relationships with her customers. They chose to buy most of their windows from Dawn because she provided good service.

But they can buy their windows from anyone they want. So when Dawn leaves Paula Payne Windows, her customers don’t have to keep buying from Paula Payne. Who’s to say they would have kept buying from Payne, rather than buying from Real Cheap, or from any of a dozen other competitors?

Ah, causation. The bane of plaintiff’s lawyers everywhere.

Horizon v. Acadia

This was essentially the damages problem in Horizon Health Corp. v. Acadia Healthcare Co., 520 S.W.3d 848, 865 (Tex. 2017), which I wrote about in Texas Supreme Court Raises the Bar for Trade Secrets Damages—Again.

In that case the Texas Supreme Court essentially said the damage expert’s assumptions about what the departing employee would have generated if he had stayed at the company were just too speculative.

This is really the fundamental problem with non-compete damages, and why the amount of damages the plaintiff claims is often inflated.

You could almost write a whole blog post about the problems with calculating non-compete damages, even when you use the right measure of damages.

And I will.

____________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

Leave a Comment