I was telling my 11YO son about a new client, and he says “you know, Daddy, when you think about it, you really make money off the misfortune of others.”

Ouch. I could respond by saying that we live in a world where people have disputes, and lawyers serve a necessary function by helping people resolve disputes under the rule of law.

But what if we lived in a world where there was no crime, and people didn’t fight over money? Lawyers like to think they serve justice, but wouldn’t we be better off in a more just world where disputes disappear, making lawyers unnecessary?

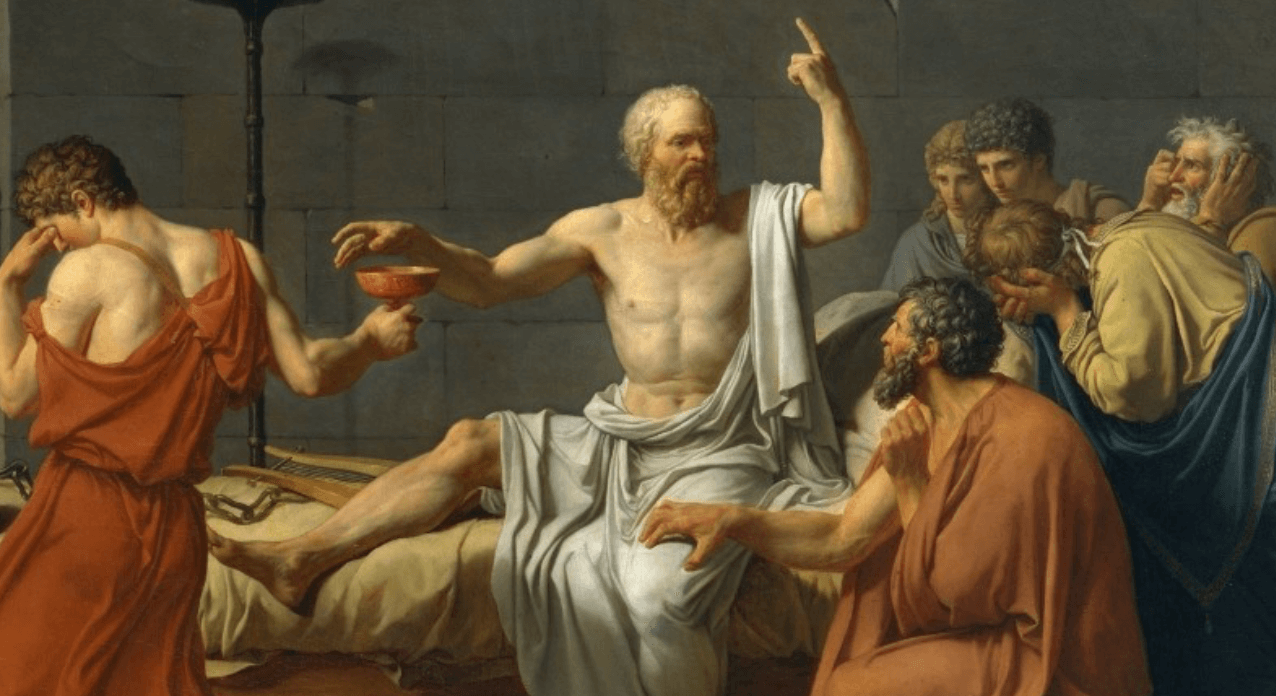

Perhaps we should consult the greatest book about justice, which—sorry, John Rawls—was written over two thousand years ago.

Let me take you down . . .

In Plato’s Republic, Socrates went down to the Piraeus and made a bold claim: justice requires that the city’s children be raised in common, not by individual families.[1]

His audience is shocked, but there is a certain logic to the claim. There is perhaps no greater source of inequality than the family. The children of rich parents have all the advantages, while the children of poor parents have it much harder. That was just as true in ancient Athens as it is today. If there is to be real justice—i.e. fairness—then the traditional family must be abolished, Socrates suggests.

And while we’re at it, we’d better get rid of private property too.[2] That’s another source of injustice.

Then, with women, children, and property shared in common among the city’s elite “guardian” class, “lawsuits and complaints against one another [will] vanish from among them thanks to their possessing nothing private but the body, while the rest is common.”[3]

Thus, Socrates suggests that a just society requires a sort of “communism,” although that term would be an anachronism in ancient Greece.

This sounds dangerous, of course, especially to us moderns who have seen the catastrophic results of 20th-century totalitarianism. It starts with lofty talk of remaking culture and society and ends with “reeducation” camps. Is that really what Plato—through his character Socrates—thought justice requires?

That question is subject to interpretation and debate. One interpretation is to take Socrates at face value. When he says that justice requires a sort of communism, he really means it. He’s advocating that kind of society.

Another interpretation says that Socrates is serious, in a sense, when he says that justice requires abolishing the family and private property. But it’s one thing to say what justice demands, it’s another to say what should be done. Justice, after all, is not the only human good. Perhaps the lesson of Plato’s Republic is that a utopia of justice would actually be a kind of dystopia.

That’s a sober lesson. It means that even the best society will have to make tradeoffs between justice and other values, and that’s a messy proposition. By asking us to imagine what a perfectly just city would look like, Plato forces us to confront that tension.

He’s a real nowhere man

This reminds me of another famous guy who asked us to imagine what a utopian world would look like. John Lennon released the album Imagine in 1971. Surprisingly, the iconic title track never reached no. 1 on the US charts, peaking at no. 3 that year. But since then, “Imagine” has become Lennon’s greatest post-Beatles hit.

Musically, it is an almost perfect pop song. That piano lick with the reverb and just a hint of the blues, Phil Spector’s ethereal but not too-syrupy strings, the tasty drum fills, and of course, John’s incomparable vocal. It’s no wonder millions of people, young and old, have downloaded the song from iTunes.

But not everyone is a fan. Behind that majestic music are some lyrics that are, let’s face it, kind of dark when you think about it.

I imagine Lennon himself would be bemused to see his provocative song embraced as a classic by middle America, to the point where you might hear it at a kid’s ballet recital. It’s how Bruce Springsteen must feel when “Born in the USA” is played at political rallies. What countercultural revolutionary wants to see his musical manifesto turned into something like the soundtrack for a Coke commercial? It’s supposed to make people uncomfortable, not teach the world to sing.

“Imagine” is especially jarring if you’re religious. Right off the bat, Lennon hits you with “imagine there’s no heaven.” Then, later, just in case you missed it, he comes back with “and no religion too.”

Granted, he never says “imagine there’s no God,” but he comes pretty close.

Then Lennon goes after two more things most Americans hold dear: patriotism and capitalism. “Imagine there’s no countries,” he sings in the second verse, “it isn’t hard to do.” And in the third verse he takes aim at private property. “Imagine no possessions, I wonder if you can.”

Not just equal possessions, no possessions. That is hard to imagine, and not very appealing.

(The common objection that it’s hypocritical for a rich rock star to sing about “no possessions,” while understandable, has always struck me as pretty weak sauce. Would the line suddenly become valid if sung by a poor person?)

But for me, the lyric in “Imagine” that everyone, regardless of political or religious beliefs, should have a real problem with is the line “nothing to kill or die for.”

That line is in the context of nationalism, coming right after “imagine there’s no countries,” and let’s remember, this was in the middle of the Vietnam War, which Lennon despised. So maybe the point was to criticize excessive militarism.

But still, if you take that line literally, it paints a picture of a world that would be pretty bland and joyless.

Nothing to kill or die for? Think about all the great literature, poetry, and cinema that would make no sense if there were nothing worth dying for. No Odyssey, no Les Miserables, not even Saving Private Ryan. And Shakespeare? Forget about it. His tragedies and histories are all about people dying for things they love more than life itself.

Getting rid of those things might make the world more just, but a lot less interesting.

Not only that, but nothing to kill or die for suggests no loved ones. Think about the things in your own life that you would lay down your life for. Yes, of course, God and country and justice and all that, but most of you probably thought about family members first. Is Lennon really saying that a world without family would be a utopia?

Better free your mind instead

Maybe we have it all wrong. Maybe John Lennon wrote “Imagine” to make us see that a world without countries, religion, possessions, and things worth dying for would actually be a dystopia. Perhaps it’s an ironic anthem.

That’s an interpretation, but an unlikely one. Just considering the face of the lyrics, the final line of the song is “I hope someday you’ll join us, and the world will live as one.” That sounds like a fairly earnest call to action. Then when we look outside the lyrics, the extrinsic evidence tells us that the song’s critique of religion, nationalism, and materialism aligns pretty well with the beliefs Lennon espoused in interviews.

In short, the ironic interpretation of “Imagine” doesn’t seem very plausible.

On the other hand, John Lennon was fond of ambiguity. This is the guy who sang “I’d rather see you dead, little girl, than to see you with another man” before he wrote the hippie anthem “All You Need Is Love.”

Even more famously, his song “Revolution” reads like a critique of 60s radicals who embraced the idea of violent Marxist rebellion. “But when you talk about destruction,” he sang on the original single version (the fast one), “don’t you know that you can count me out.” He was all about giving peace a chance.

Or so we thought. Later, when the Beatles released the slower, doo-wop version of “Revolution” (the one on the White album), John sang “don’t you know that you can count me out . . . in.”

Out . . . in. What was that all about?

This ambiguity suggests we need to consider Lennon’s whole body of work, and when we do that, a more complex picture emerges.

Just like starting over

Nine years after Imagine, John Lennon released a comeback album called Double Fantasy. I consider it his best solo album, but strangely, there’s nothing on it about politics. Instead, the songs were all about relationships. (“Woman, I can hardly express, my mixed emotions at my thoughtlessness.”)

What happened? Did John go soft?

One thing that happened is that John’s son Sean was born in 1975. At that point, Lennon did something almost unimaginable for a rock star who stood at the top of the world. He quit making music, became a house husband, and stayed home with his kid, changing diapers and watching Sesame Street.

This eventually led to another song with a memorable piano riff: “Watching the Wheels.” It responds to the questions people kept asking John during his self-imposed exile from show business. “Don’t you miss the big time, boy, you’re no longer on the ball?”

But the song on Double Fantasy that has really resonated with people is “Beautiful Boy,” a musical love letter to John’s son. Even if you don’t know the song, you probably recognize its signature line: “life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans.”

Everyone can relate to that, especially if you have children. We all have big plans when we’re young. Some want to get rich, or famous, or both. Others want to make the world a better place.

Raising children has a way of bringing us back to reality. This is precisely why Socrates thought the family would stand in the way of complete justice.

And the hard truth is, sometimes having a family gets in the way of those big plans you had. But you learn that the best stuff in life is what happens along the way. You’d think that people would have had enough of silly love songs, but you look around you and you see it isn’t so.

I think this points to a third possible interpretation of “Imagine.” Maybe we need to pay more attention to the title.

Maybe the point is not to get rid of everything we care about and fight over. “Imagine” suggests that the things human beings love the most can also be the very things that make us behave the worst. But by imagining a more just world, we can at least remind ourselves not to let our selfish concerns for our own families, possessions, and beliefs feed into greed, intolerance, and violence.

If that means less work for lawyers, I can live with that. Maybe I can have a second career as a rock star.

__________________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020 and 2021.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients.

[1] “All these women are to belong to all these men in common, and no woman is to live privately with any man. And the children, in their turn, will be in common, and neither will a parent know his own offspring, nor a child his parent.” The Republic (On the Just), Book V, 457d (Basic Books 2d ed. 1991, trans. Bloom).

[2] “There mustn’t be private houses for them, nor land, nor any possession.” Id. at 463c.

[3] Id. at 464e.

Leave a Comment