One of my goals for 2022 as a lawyer is to lose more in the courtroom.

Ok, not exactly. I don’t really want to lose. In fact, I hate to lose. And if you’re one of my clients, don’t worry. I certainly don’t want to lose your case. I always go to the courtroom prepared to win.

But there are some benefits to losing. More about that later.

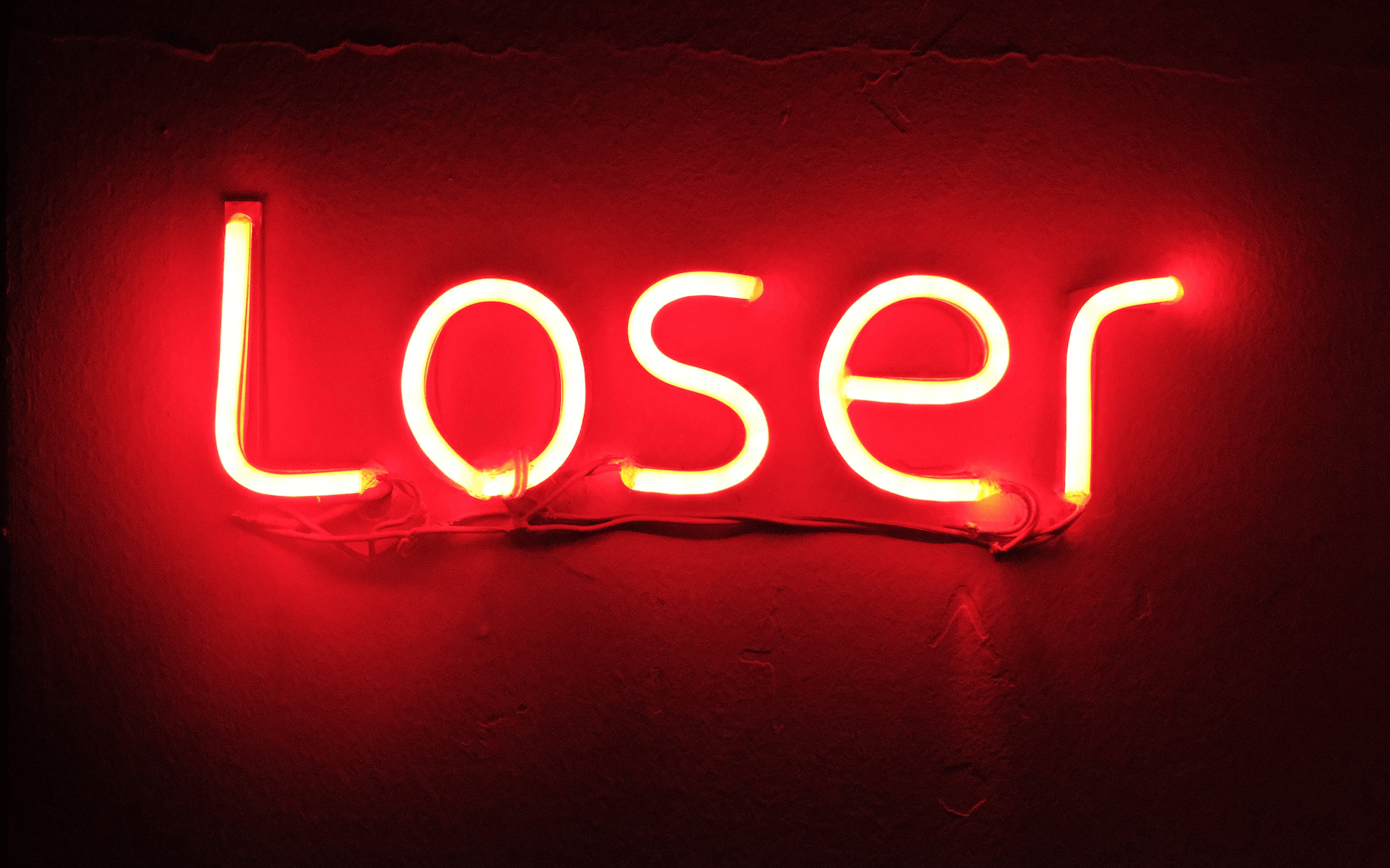

When I think about losing, I instantly hear an old Beatles song. “I’m a loser,” John Lennon sang in 1964. “I’m a loser, and I’m not what I appear to be.”

You’re not likely to find that in a lawyer’s website profile, especially a litigator.

No, most litigator profiles are going to tout the wins. You’ll see a lot of “obtained $5 million jury verdict in trademark infringement lawsuit.” You probably won’t see “$10 million trade secrets judgment entered against my client.”

Why is that?

Well, duh. Because clients want litigators who are winners, not losers.

Ethical Issues

But is it really that simple? For one thing, there’s a potential ethical issue. When a lawyer publicizes a past result obtained, that’s advertising, and there are ethical limits on lawyer advertising.

For example, in Texas, where I practice, Rule 7.01 of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct says that a communication concerning a lawyer’s services must not be false or misleading.

The “false” part is pretty simple. If you claim you’ve obtained ten judgments of over a million dollars and you’ve really only obtained five, that’s a problem.

The “misleading” part is harder. A statement can be true, but misleading, if it omits important information causing a reasonable person to get the wrong impression. As Texas Rule 7.01(a) says, a statement is misleading if it “omits a fact necessary to make the statement considered as a whole not materially misleading.”

Rule 7.01(a) goes on to say that a statement is misleading “if there is a substantial likelihood it will lead a reasonable person to formulate a specific conclusion about the lawyer or the lawyer’s services for which there is no reasonable factual foundation, or if the statement is substantially likely to create unjustified expectations about the results the lawyer can achieve.”

To take an extreme example, suppose a lawyer sues Big Refinery Co. for wrongful death, Big fails to answer because of a paperwork snafu, and the lawyer gets a $1 billion default judgment. If the judge later sets aside the judgment, it would be misleading for the lawyer to put up a billboard that says “Hire the Lawyer who got a billion-dollar judgment against Big Refinery!”

But that’s the kind of thing that happens in personal injury practice, some of you are thinking. The world of business litigation is more genteel.

And yet, just about all business litigators omits their losses from their list of “past results” or “representative matters.” Isn’t that a little misleading? And potentially unethical?

This is fun to think about, but it’s probably not an ethical violation. I think the main reason we allow this is what I’ll call the Leonard Cohen Defense. Everybody knows lawyers do this, so it’s not like potential clients are going to get the misleading impression that “this lawyer never loses!”

Still, while it’s understandable that a lawyer would publicize wins and not mention losses, and probably not an ethical violation, is the information about wins actually useful to potential clients?

I see some reasons why the information is not that helpful.

When is a Win Not a Win?

First, there’s the problem of defining wins and losses in litigation. Suppose a lawyer gets a verdict and judgment for $500,000 in a trademark infringement case and the judgment is paid. Is that a win?

It sure sounds like it, but I’m sure my lawyer readers are saying “it depends.” Let’s say the plaintiff was asking for $3 million in damages, and the $500,000 judgment was entirely paid by insurance. And suppose the defense had offered $1 million to settle. The defense lawyers would consider the result a win for their client, and justifiably so.

Even then, it might be hard to say who won and who lost. Maybe the plaintiff’s lawyer knew the jury wouldn’t award $3 million and was happy with $500,000. Or suppose the lawsuit resulted in the defendant backing off and changing its marketing strategy, which was what the plaintiff really wanted.

The point is that it’s difficult to know if a litigation result was really a win or a loss, without knowing all the surrounding circumstances.

Still, knowing that a lawyer got a half million-dollar judgment is better than not knowing anything, if you’re a prospective client looking for a lawyer to handle the same type of case. At least it tells you that lawyer has some experience in that area and has had some success.

But I wouldn’t put too much stock in it. A second problem is sample size.

Sample Size

First let me acknowledge there are some lawyers who have tried a lot of civil cases to a jury verdict.

But their numbers are dwindling. If we set aside insurance defense and plaintiff’s personal injury, these days most of the remaining litigators just haven’t tried a large enough number of cases to have a useful sample size. (I say “most,” because again, there are some business litigators who have tried a large number of cases, but they are the exception, especially for lawyers under 50.)

I put myself in this category. I’ve handled jury trials and stand ready to do so again, but I’d say over 95% of my cases settle before trial. So if you asked me my trial win-loss rate, that information would not be very useful, because my sample size is small. I’d bet most business litigators are in the same boat.

And there’s another reason, perhaps less obvious, that would make my sample even less useful.

Would you believe that lawyers don’t really get to pick which cases go to trial? And the cases that do go to trial tend to be the weird ones.

Why is that? Well, think about it. The cases that go to trial are, by definition, the ones that don’t settle. Now ask yourself, what does it mean if a case doesn’t settle before trial? As one senior lawyer said to me early in my career, it usually means someone has miscalculated. If the parties are represented by competent counsel, behaving rationally, and evaluating the risks properly, the case should settle.

But those are big “ifs.” In my experience, when a case does go to trial, there’s usually some distorting factor. Often it’s because the case is personal. The last two jury trials I had both fall into this category. Sometimes it’s because at least one side thinks their case is stronger than it really is. Or sometimes both of those things.

And don’t think that “personal” cases are limited to ones where there are individual parties. Even big corporations are run by people, and those people have emotions, especially pride.

The point is that when cases go to trial, often it’s not because of the merits of the case, but because of people miscalculating or acting emotionally. It’s not like the lawyers get to pick their favorite cases to go to trial.

So when you look at the cases any given lawyer has taken to trial, in most cases that sample is probably not very useful.

Ok, a potential client might say, but I’d still like to know a lawyer’s success rate before I fork over a big deposit for my litigation matter. All else being equal, I’d rather my lawyer have a high win-loss percentage than a low one.

I get that. Sort of.

But I see some problems with a high success rate that may not be obvious.

Afraid to Lose?

One is that as a lawyer you often learn more from the losses than the wins. I found this out the hard way early in my career when I was assigned a fairly routine collections case in small claims court. The opposing counsel showed up with a document my client hadn’t provided me, and we lost the case. I was pretty down about it, but the more senior lawyer who assigned me the case said “well, if you had won you wouldn’t have learned anything.”

Yes, as a lawyer sometimes you learn more from the losses than from the wins.

Ok, but what good does that do the client? That’s a good question, but I think the client can also benefit from a lawyer who has some losses.

Here’s the thing. A lawyer who has very few losses in the courtroom may be too risk averse, i.e. too afraid to lose.

And a lawyer who is too afraid to lose may give up too much in settlement negotiations. That is one kind of “loss” that you will never see on a lawyer profile: settling on terms that were too unfavorable for the client.

Yet that is, in fact, a loss. Sure, the client may have agreed to it, but it’s no less a loss than a client who wins a $500,000 judgment but could have gotten $1 million in settlement. It’s why that same mentor liked to say “I’d rather lose at trial than lose in settlement.”

This gets at what I meant when I said I hope to lose more this year. It’s not so much that I want to lose more, it’s that I want to be less afraid to lose. That, I hope, will benefit my clients.

And who knows, maybe I will start posting my losses on my firm’s website.

____________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm. Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020 and 2021.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

Leave a Comment