Two spots at the top of the charts

This is my third “Election Edition” post. The first was in 2016, the second in 2018. I figure every two years is often enough for Five Minute Law to weigh in on politics.

In the last one I repeated the assertion by one of my college professors that Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy In America is the second-best book on American politics.

That means the best one must be the Federalist Papers, which are now enjoying a renaissance, due partly to the prominence of “Originalism” in debates over Supreme Court nominees, but mostly—let’s be honest—because of the smash Broadway musical Hamilton.

Thanks to Hamilton, hip schoolkids around the country now know that the Federalist Papers were not really a book, but a series of 75 essays defending the new federal Constitution to the public, written by John Jay (until he got sick), James Madison, and of course, Alexander Hamilton, who wrote “the other 51!”

Still, we’ll call it a book for simplicity.

Of course, not everyone is a fan. The progressive left is uneasy with the Federalist Papers (at best), considering they were written by three wealthy white men to justify a Constitution that treated enslaved African-Americans as three-fifths of a person and denied political rights to women. Two of the authors even owned slaves!

Conservatives, on the other hand, seem to love the Federalist Papers, but they may not like everything they find in them. It is ironic that “populist” movements like the Tea Party like to invoke the rhetoric and imagery of the founders, when many of the founding thinkers—including Madison, and certainly Hamilton—were decidedly un-populist or even anti-populist.

So, the marriage of the arguably elitist political thought of the Federalist Papers with the “populist” strain of contemporary American conservatism was always an uneasy one (even before Trump).

Still, the Federalist Papers remain at the top of the charts when it comes to books about American politics. It’s like even if you think the Beatles are overrated, you have to grudgingly admit they are the most important rock band.

On the other hand, just as some people will make a case for the band in the number two spot (that would be Led Zeppelin, with due respect to the number three Rolling Stones), there is a case to be made for putting ADT (that’s what I call my man Tocqueville) ahead of Publius.

I mean, ADT should at least get extra points for correctly predicting the rise of the United States and Russia as the world’s major powers, over a century before it happened.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Before we reevaluate which book really deserves the number one spot, perhaps we should step back and ask ourselves what problem the authors were trying to solve.

The problem, in a word, was democracy.

The problem with democracy

To say that democracy was the problem is a little jarring for contemporary ears, on both sides of the spectrum. Almost everyone today—Republican or Democrat—says they are on the side of the people. You’re not going to find any mainstream politicians openly advocating for some kind of aristocracy or dictatorship.

But democracy was the problem both Publius and ADT were trying to solve. Granted, in both cases they were also concerned with the more pragmatic issue of effective government, but the chief philosophical question was how to prevent democracy from destroying liberty, and itself.

This made the project of the American founders unique. Previously, there were pro- and anti-democratic thinkers, but the founders—at least Madison and Hamilton—were different: pro-democratic statesmen grappling with how to save democracy from itself.

The problem from their perspective was that the American Revolution had set loose egalitarian passions that threatened to consume life, liberty, and property like a wildfire. The founders’ proposed U.S. Constitution was designed to implement democratic principles—it is not as if they were proposing some return to monarchy or aristocracy—but it was also designed to constrain them.

Madison made this clear in Federalist No. 10, perhaps the most “philosophical” of the Papers. The problem, he said, was “faction,” by which he meant a group of citizens united by devotion to some passion or cause opposed to the general welfare. Today we would call it an “interest group.” Madison seemed to view factions as the greatest threat to stability and freedom in a democracy.

Federalist No. 10 tells us several things about these factions.

First, Madison said factions are unavoidable in a free country. When people are free to form opinions and to express them through politics, there will necessarily be conflicting opinions. The only way to avoid that would be to take away the freedom, a cure that would be worse than disease. There are no factions under communism, for example.

Second, under a democratic form of government, majority factions are more to be feared than minority factions. That’s because the “republican principle”—essentially majority rule through representative democracy—takes care of minority factions.

The problem of a majority faction, on the other hand, cannot be solved with majority rule. That’s true almost by definition. Something else is needed.

This is where contemporary political scientists—especially progressives—are going to object. Isn’t the very idea of a “majority faction” an oxymoron? If a faction is defined as a group pursuing its own interest as opposed to the general welfare, how can a majority be a faction? In a democracy, we decide what is good for the whole based on what the majority says. There’s no other objective standard.

This is where the elitism comes in, both in abstract and concrete terms. In the abstract, Madison believes the majority can be a faction because the majority can be wrong about what is good for the country.

But in concrete terms, who is Madison talking about when he refers to a majority faction? To put it bluntly, he’s talking about the poor.

For the first time, I feel wicked

Yes, the poor. That’s who the majority is, or was at the time (and throughout most of history).

Madison makes this clear in two ways. First, he identifies “those who hold and those who are without property” as two competing factions. Same for creditors and debtors, he says.

Then he makes it even more plain when he names the evils he is most worried about a majority faction enacting: “A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project” (emphasis added).

A-ha! Now we’ve got him. You don’t have to be a Marxist to question whether all this talk about “factions” is really just an excuse–an ideological superstructure, you might say–for preventing the poor from oppressing the rich, protecting creditors from debtors, and stopping those without property from overrunning those with property. It’s about the “haves” and the “have-nots.”

The materialist view is that Madison, a wealthy landowner, was merely concerned with protecting himself and his rich friends and family. And perhaps he was, at least in part.

But that cynical view misses something important. I think Madison was not just concerned with protecting the rich from the poor, but with protecting democracy itself.

You see, allowing the poor to oppress the rich poses two problems. First, the rich are not just going to sit there and take it. They are going to push back, even if that means seizing power through undemocratic means. Second, there is the ever-present tendency of the people—i.e. the poor, less educated people—to support a certain kind of leader: the demagogue.

The problem with demagogues

Here we can look to Hamilton, Madison’s famous frenemy, for guidance. In a later letter to George Washington, Hamilton offered this striking portrait of the demagogue:

When a man unprincipled in private life desperate in his fortune, bold in his temper, possessed of considerable talents, having the advantage of military habits — despotic in his ordinary demeanour — known to have scoffed in private at the principles of liberty — when such a man is seen to mount the hobby horse of popularity — to join in the cry of danger to liberty — to take every opportunity of embarrassing the General Government & bringing it under suspicion — to flatter and fall in with all the non sense of the zealots of the day — It may justly be suspected that his object is to throw things into confusion that he may “ride the storm and direct the whirlwind.“

Hamilton’s description teaches us something valuable: the demagogue is a uniquely democratic threat to democracy. This kind of despot would not come to power by restoring the institutions of monarchy or aristocracy, but by mounting the “hobby horse of popularity” and riding the democratic storm.

In other words, the demagogue draws his support from the majority faction.

When we put this together with the reasoning of Federalist No. 10, we see that democracy itself does not give us the solution for the demagogue problem. That’s because the demagogue’s MO is to appeal to the common man, the “silent majority,” the “real Americans.”

So what can we do? Madison’s answer in Federalist No. 10 has essentially two parts: republicanism, meaning representative democracy, and “enlarging the sphere.”

Enlarging the sphere meant combining the 13 colonies into one nation with a representative democracy to rule it. You can read Federalist No. 10 yourself to see how Madison thought these two principles would solve the problem of faction.

In the simplest terms, Madison’s solution to factions was more factions. In a larger nation, competition between factions would keep any one faction from gaining too much power. And this healthy jockeying between rival factions—combined with the institutions of a representative democracy—would make it more difficult for a demagogue to ride a wave of popular passion to power.

The prospect of a demagogue mounting the hobby horse of popularity was no philosophical abstraction at the time. Soon a democratic revolution would come to France as well, leading to chaos, instability, and eventually, Napoleon Bonaparte.

Ah, France. That brings us back to Tocqueville.

You down with ADT?

Alexis de Tocqueville was a young French aristocrat who wrote his two-volume masterpiece De La Démocratie en Amérique in the 1830s after a nine-month trip to America with his BFF, Gustave de Beaumont.

I explained the project of Democracy In America in my last Election Edition, so I won’t repeat all of that here. Suffice to say that Tocqueville viewed democracy—by which he meant a social condition of equality as opposed to a landed aristocracy—as inevitable, and his chief concern, much like Madison and Hamilton, was how to prevent democracy from extinguishing freedom. He hoped to learn lessons from America, a relatively healthy democracy, that could be applied to his own post-revolutionary France, a troubled democracy.

In short, like Madison in Federalist No. 10, ADT was concerned with preventing or tempering the “tyranny of the majority.”

He answered this question largely by observing and describing. He praised the U.S. Constitution and the founding generation that created it, but he opined that there was something more important that maintains a democratic republic in America: “mores,” or what today we might call norms. I wrote about this last time in It’s The Norm: French Lessons on the Limits of Law.

ADT’s analysis of mores gives his book deeper insight into what restrains the tyranny of the majority than the Federalist Papers. In fairness, this was because ADT gave himself a broader assignment. Publius wrote for the narrower purpose of persuading Americans to support the proposed Constitution. Still, I give Democracy In America extra points for its broader perspective.

But regardless of scope or perspective, who got it right? Who predicted better?

Interest groups, money, and oligarchy

Let’s start with the question of minority factions. Here, I think we must dock Madison some points for his assumption that the “republican principle” would prevent minority factions from imposing their will.

It hasn’t really turned out that way, has it? You might even characterize the American form of government as rule by special interest groups. The problem is that a well-organized interest group that intensely cares about an issue will usually win out over a more diffuse public interest.

And that’s true even before you add money to the equation.

Of course, money was a factor at the time of the founding too, but I’m not sure the founders foresaw just how important money would be to politics in the American form of government. Money—mainly in the form of campaign contributions—is the very oxygen American politicians breathe. A well-funded and intensely supported minority interest group will wield disproportionate influence over the laws, violating Madison’s republican principle.

Worse yet, the influence of money is not spread evenly among the factions. Sure, the little guys can band together to raise money—especially now with social media—but overall the politicians’ dependence on campaign cash skews the process in favor of one particular minority faction: the rich.

And it has gotten worse for the poor, who are no longer the majority. Today, the middle class is the majority, which explains why politicians on both sides speak its name with such reverence. Even the Democrats rarely talk about the “poor”—that’s so passé. It’s always the “middle class.”

In short, I think Madison underestimated the oligarchic element in American politics.

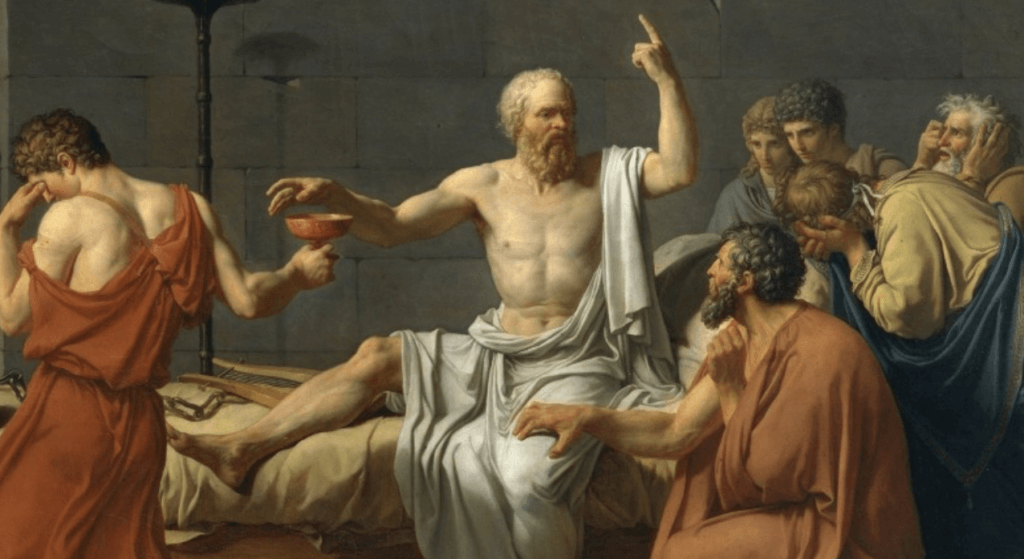

“Oligarchy” comes from the Greek oligarkhia, which combines oligoi (“few”) with arkhein (“to rule”). So let’s consult a Greek on its meaning. Aristotle classified political regimes based on two factors: who rules, and in whose interest they rule. Thus, an “aristocracy” was the rule of the few in the interest of the whole city, while oligarchy was the rule of the few in their own interest.

I think if Aristotle were to view American government today, he would see it as a mixed regime, with elements of democracy, oligarchy, and—if he’s being charitable—aristocracy.

Madison and friends hoped that their constitutional system would encourage a sort of “natural aristocracy” where the democratic process would put the best people in charge. Thankfully, through much of U.S. history we have been luckier than we deserve on that score. But overall, I fear that Federalist No. 10 was too optimistic in its expectation that the principle of majority rule would prevent oligarchic factions from holding sway.

ADT, on the other hand, saw that the industrial age could produce a kind of oligarchy within American democracy.

An industrial oligarchy?

His prediction came in Volume Two of Democracy In America, in a short chapter titled “How Aristocracy Could Issue From Industry.”

ADT begins by noting how modern industry degrades the worker: “As the principle of the division of labor is more completely applied, the worker becomes weaker, more limited, and more dependent.” As a result, “at the same time that industrial science constantly lowers the class of workers, it elevates that of masters.” The conclusion: “What is this if not aristocracy?”

This new industrial aristocracy—really an oligarchy in Aristotelian terms, because ADT clearly expected it to pursue its own narrow interests—would be less noble than the old landed aristocracy but also less dangerous, ADT says.

It would be less dangerous primarily because of class mobility. Industrialization could lead to “some very opulent men and a very miserable multitude,” ADT explains, but “although there are rich, the class of the rich does not exist.”

By this he means no “class” of the rich comparable to the aristocrats of old. Membership in the new industrial aristocracy would be based on money, not land or family lineage, and money comes and goes.

“An aristocracy thus constituted cannot have a great hold on those it employs,” ADT says, “and, should it come to seize them for a moment, they will soon escape it.” For this reason, while ADT predicted the manufacturing aristocracy would be “the hardest that has appeared on earth,” he thought it would be the “least dangerous.”

Of course, the Industrial Revolution and the Gilded Age would produce precisely the kind of “opulent” industrial oligarchs ADT predicted. And just as he anticipated, the workers would push back. We would see the American working class assert itself in the Progressive era and the New Deal, and by the 1950s and 1960s the balance of power had shifted.

“Still,” ADT warned about the emerging industrial aristocracy, “the friends of democracy ought constantly to turn their regard with anxiety in this direction; for if ever permanent inequality of conditions and aristocracy are introduced anew into the world, one can predict they will enter by this door.”

This warning of an undemocratic threat to democracy is music to our modern democratic ears. And its prescience is one of the reasons I’m giving Democracy In America a slight edge over the Federalist Papers.

And yet . . .

Democratic versus anti-democratic threats to democracy

The greatest value in both the Federalist Papers and Democracy In America is that they fill in our modern blind spot. All of us today—Democrat or Republican—are small “d” democrats, in the sense that nobody today seriously believes that one class of people is by nature more entitled to rule than anyone else. And as democrats, we have a blind spot for democratic threats to democracy.

As I once learned from Prof. Arthur Melzer, in a democracy you have essentially two kinds of dangers: democratic dangers and undemocratic dangers.

We have no difficulty seeing the undemocratic dangers, the ways that we fall short of the democratic ideal. Through our democratic lens, these threats stand out in red against a grey background.

We have more trouble seeing the democratic threats to democracy. It’s as if they were red but we can’t see them clearly because we’re wearing red-tinted glasses.

This makes the insights of Madison and Hamilton all the more valuable because, while they supported representative democracy, they were basically—let’s face it—elitists. The same is true of Tocqueville. And while we may not like elitists, they have some important things to teach us.

(If you want to take this idea even further, try the aforementioned Aristotle, who didn’t think democracy was the best form of government, and even seemed to defend slavery.)

On the other hand, perhaps these elitists have their own blind spots, as we have seen. In Federalist No. 10, Madison displays great insight into the dangers of a majority faction, but perhaps he failed to fully appreciate the dangers posed by special interest groups generally, and by an oligarchic minority faction specifically.

And then there is another glaring blind spot in the Federalist Papers, one we have yet to mention despite its enormous importance in American history and politics. I’m talking of course about the question of race. How can we talk about “tyranny of the majority” in America without addressing the tyranny of white over black?

Race in American politics

Madison does refer a couple times to banning importation of slaves (in Federalist No. 38 and No. 42), and he addresses the Three-Fifths Compromise in Federalist No. 54. But the Federalist Papers didn’t tackle the hard questions about how a system of slavery can exist within a democracy in the long term.

One assumes the subject was simply too sensitive, and outside the scope of the assignment. The point was to persuade people to support the new Constitution, and even Hamilton was not about to antagonize the touchy Southern slave states by attacking slavery. So perhaps we can forgive the Federalist Papers for not taking on the thorny subject.

America’s favorite philosophizin’ Frenchman, on the other hand, had no such qualms.

Near the end of Volume One of Democracy In America, there is a long chapter titled “On the Principal Causes Tending to Maintain a Democratic Republic in the United States.” That is the chapter that includes the discussion of mores referenced earlier.

At the conclusion of that chapter, you feel ready to defend freedom from the tyranny of the majority, armed with ADT’s wisdom. But then he throws you a curve ball. There’s one more chapter: “Some Considerations on the Present State and the Probable Future of the Three Races That Inhabit the Territory of the United States.” (He’s referring to whites, African-Americans, and Native Americans.)

It’s as if to say, “oh, by the way, before we finish up, there’s just this wee little issue of race that we need to talk about.” And then he hits you with the longest chapter of Volume One.

I recently heard someone say racism is a central part of the American story, but so is overcoming racism. Either way, if you’re going to write the best book about American politics, you’re going to have to tackle the topic.

So what does ADT have to say about race in America?

I’ll tell you in two years.

______________________________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm. Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020 and 2021.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients.

Leave a Comment