It was a rite of passage this past year in the Wolfe casa, when I watched the classic 1980 film The Blues Brothers with my 11YO son, just as I had done with my dad back in the day.

Some of you will remember the opening scene. “Joliet” Jake Blues is finally getting out of prison. Dressed in his jailhouse fatigues, he is led to the property room to claim his personal belongings. He steps up to the counter, and an officer holding a clipboard glares at him (played by none other than Frank Oz of Muppets and Yoda fame). The two escorting officers pull him back to stand behind the yellow-taped line on the floor.

“Sign here,” the officer sneers. Jake sarcastically plants his feet behind the yellow line while cartoonishly leaning forward to sign his “X” on the line. Right off the bat you get a sense of Jake’s personality.

I experienced something similar as a teenager when I went to get my driver’s license. I walked up to the counter, and the lady behind it said “please stand behind the line until you’re called.” Afterwards, I remember my dad saying something like “you give people a little bit of power . . .”

I’ll come back to that.

The 2020 bar exam controversy

You may have heard there has been some controversy about the bar exam this year. The problem is obvious. The last thing you want in the middle of a pandemic is hundreds of test-takers assembled in one big room together for hours on end.

This has presented bar examiners with several options. I’ll list them in order from worst to best:

1. Cancel the exam and just wait until next year. Graduating law school students can just figure something out for a year.

2. Grin and bear it. Stick with the in-person bar exam, but maybe with some extra social distancing. How bad could it be?

3. Switch to an online exam. If monitoring the test-takers is too much of a logistical challenge, then just make it an open-book exam (as many exam critics have already suggested).

4. Considering the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 epidemic, the threat of spreading the virus to test-takers, the anxiety that the threat of the virus must visit on already-stressed-out examinees, and the fact that the bar exam is not really that essential in the first place, grant admission to the bar based on diploma privilege—at least just this one year.

(Diploma privilege means accepting graduation from an accredited law school in lieu of passing the bar exam.)

My ranking of the options is of course just my opinion, and there are pros and cons to each. I’ll concede this is not an easy issue for bar examiners to deal with. Same for the state supreme courts that, in most cases, ultimately oversee the bar examiners.

But that’s about the best I can say for the bar examiners. Overall, if I had to grade their collective response to the COVID-19 crisis, they would get an F. Ok, maybe some of them would get a C, if we’re being charitable.

They should have just made it simple and granted diploma privilege for this one year. That would earn an A.

Granted, as indicated earlier, my grade is based on the premise that the bar exam is not really that valuable. If my premise is wrong, then maybe my grade is too low.

So it comes down to this: what is the real purpose of the bar exam, and how well does it serve that purpose?

Are you ready for some football?

Let’s put it in football terms. NFL teams use the scouting combine to help evaluate college players for the draft.

At the combine, players run a gauntlet of physical fitness challenges that includes things like the 40-yard dash, the vertical jump, and bench pressing 225 pounds as many times as possible. They also get interviewed and take a sort of IQ test called the Wonderlic.

Of course, the tests at the combine are just part of the puzzle. It’s a sports talk show cliché for some former player to say, “I don’t care how good he looks running around in shorts, let me see him on the field in pads getting hit.”

But the physical tests at the combine give the teams some relevant information they find valuable.

No, on game day you don’t get points for running a 40-yard dash in a straight line with no pads for time. But if the defensive back you’re scouting has a subpar time on the 40, that tells you he may not have the speed needed to stay with a Tyreek Hill streaking down the sideline. Seeing that prospective offensive lineman bench press 225 pounds like it’s nothing gives you some idea of what he can do to a blitzing linebacker.

In the same way, testing future lawyers on their knowledge of specific areas of law is obviously not the same as watching them actually practice law, but it gives you some indication of their legal acumen, right?

Well, not so much. The NFL combine is perhaps what the bar exam wants to be, but the reality is different.

Imagine you’re a college football player arriving at the NFL combine, and a team scout hands you a stack of 15 detailed rulebooks from various sports. The sports include everything from tennis to basketball to golf, and maybe—maybe—football. “You’ve got a week to memorize these rulebooks, kid, and then there’s going to be a written test.”

That’s the bar exam.

You can see the problem. First, knowing all the intricate rules to football is no test of how well you are prepared to play football. Second, knowing the rules of, say, professional bowling has no relevance whatsoever to playing football.

Now, in fairness, making NFL prospects memorize these rulebooks and take a test on them might have some value. For one thing, the ability to memorize that much information and apply it on a written test would be some indication of a player’s intelligence. For another, this ordeal would give teams some sense of a player’s grit, determination, and discipline.

It would also serve as a sort of rite of passage, building camaraderie among players. Someday they’ll sit at a bar reminiscing about the experience. “You remember when we had to memorize all those crazy rules of table tennis, that was insane!”

And finally, let’s say the rulebooks include the rules of the NFL. In that case, a player’s knowledge of the rulebook might have some value, even if it’s not the thing that really matters.

So how is my combine hypothetical like the bar exam?

An exam for a bygone era?

The first problem is that the ability to memorize a bunch of legal rules and apply them on a written test isn’t even close to how lawyers actually practice law. It is both too difficult and too easy. It’s too difficult because in practice, if a lawyer doesn’t remember all the elements of the business records exception to hearsay, she’s just going to look them up. It’s too easy because real flesh-and-blood client matters don’t come in neat little fact patterns with right or wrong multiple-choice answers.

But that’s just the least of it. The bigger problem is specialization.

There was a bygone era when small-town lawyers had to know a little about a lot of different areas of law practice. You might draft a will on Monday, appear in court for a criminal defendant on Tuesday, and review an oil and gas lease on Wednesday. The typical selection of bar exam topics seems built for this kind of practice.

But hardly anyone practices like that anymore. Almost every lawyer today specializes in some specific area of law. Sure, the level of specialization varies, and some lawyers have more than one specialty, but very few lawyers now have the kind of general practice that the bar exam attempts to test for.

Let’s say a lawyer specializes in patent law. Testing that lawyer on her knowledge of criminal procedure is about as relevant as testing a wide receiver on his knowledge of the rules of baseball. That would be unnecessary and over-inclusive.

And there’s a less obvious problem. No matter what topics you pick, the bar exam is also going to be under-inclusive. I’ll use myself as an example. My practice focuses on non-compete and trade secret litigation. Sometimes I also handle trademark matters. (This is by happenstance; the two practice areas have nothing to do with each other.)

Guess what? The bar exam I took had nothing about either one of these practice areas.

How can this be? How could the Texas Board of Law Examiners set me loose on an unsuspecting public without first testing my competence in these areas of law?

The answer is twofold and, I think, illustrative.

First, in the case of trademark law, I learned it the old-fashioned way: apprenticeship. I don’t mean any kind of formal apprenticeship. I just mean that I learned it by working with a lawyer who was experienced in trademark matters. I wouldn’t call myself a trademark law expert, but it didn’t take long for me to achieve basic competence in it.

This is how almost every new lawyer learns to practice law.

Granted, there are some intrepid souls who get out of law school and immediately hang up the proverbial shingle. But we don’t need to worry too much about them. Anybody who goes that route is likely to have an unusually high amount of initiative and motivation, which I’ll bet more than compensates for lack of experience.

And that is the exception, not the rule. Very few clients hire a lawyer who just got out of law school and has no experience. So, naturally, the vast majority of new lawyers go to work under the supervision of a more experienced lawyer. Effectively, most lawyers start their careers serving an informal apprenticeship that lasts 1-3 years, or even longer.

This informal apprenticeship—not the bar exam—is the main way the profession trains lawyers for basic competence.

The second way the profession ensures competence is through self-study and the free market. Here’s what I mean. Remember I said the main focus of my practice is non-compete and trade secret litigation? I’m not too modest to say I am an expert in that area of law.

And here’s the funny thing. I didn’t become an expert on non-compete and trade secret litigation through studying for an exam on it, or even through some kind of informal apprenticeship. I learned it on my own through on-the-job training, and then tried to make a name for myself in it. Then the free market does its thing, and people who hear that I’m an expert call me up.

These examples teach us that the bar exam is neither necessary nor sufficient to ensure competency of lawyers.

Having said that, I must give the bar exam its due. Like our hypothetical NFL rulebook ordeal, the bar exam doesn’t prove nothing. Passing the bar exam is probably some indication of intelligence. It is definitely some indication of perseverance and dedication. And, like making NFL prospects memorize the rules of badminton, it may have some value as a sort of shared rite of passage.

Still, these are pretty weak justifications for the bar exam.

I think the real purpose of the bar exam is public relations. The public thinks that some test of legal competence is necessary, and that the bar exam serves that purpose. Lawyers are already an unpopular group. The last thing we want is the PR disaster of the public thinking “they’ll let anyone practice law these days, you don’t even have to take a test.”

So I get it. We probably need some kind of bar exam to assuage an already hostile public. But just among us lawyers, let’s not pretend that the purpose goes much further than that.

And with that backdrop, let’s look at how bar examiners have handled the bar exam in 2020.

What is wrong with these people?

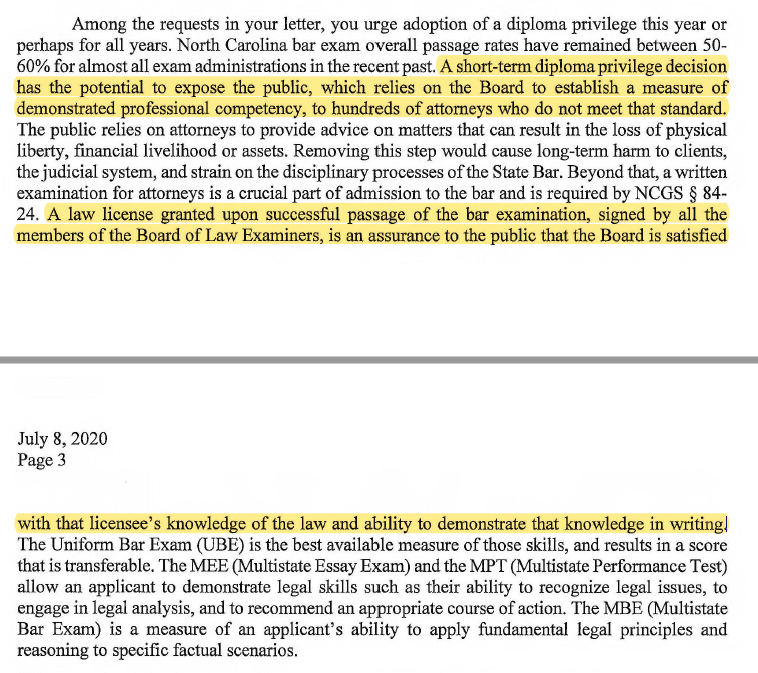

Perhaps the greatest shortcoming has been the simple failure or refusal to grasp the seriousness of the health risks of taking an in-person bar exam, combined with an inflated sense of the value of the exam. The response from the North Carolina Board of Law Examiners typifies this attitude:

For the reasons addressed above, I think this position puts too much faith in the value of the bar exam. It just isn’t grounded in the reality of how new lawyers learn to practice law.

But I will concede that this is at least a plausible position, and one the average John Q. Public probably agrees with. Reasonable people can disagree over whether temporary diploma privilege is the best way to respond to COVID-19.

The problem, though, is not so much that bar examiners have made bad decisions, it’s the way they have done it. Their attitudes have not reflected well on our profession.

Sure, I’m basing this on anecdotal evidence, but the stories I’ve seen suggest that bar examiners have reacted to the COVID-19 crisis with a disappointing combination of pettiness, arbitrariness, lack of compassion and empathy, and even outright hostility towards law school graduates preparing to enter the profession.

I’ll give you some examples.

In the hypocrisy category, let’s start with the fact that many bar examiners, while insisting that we continue with an in-person exam, have required examinees to sign COVID-19 waivers. See also the bar examiner boards that are working from home but still insist on an in-person exam.

In the procrastination category, how about waiting until the last minute to tell law school graduates studying for the bar exam that the exam has been canceled or postponed? Breaking: Florida Man cancels online bar exam three days out.

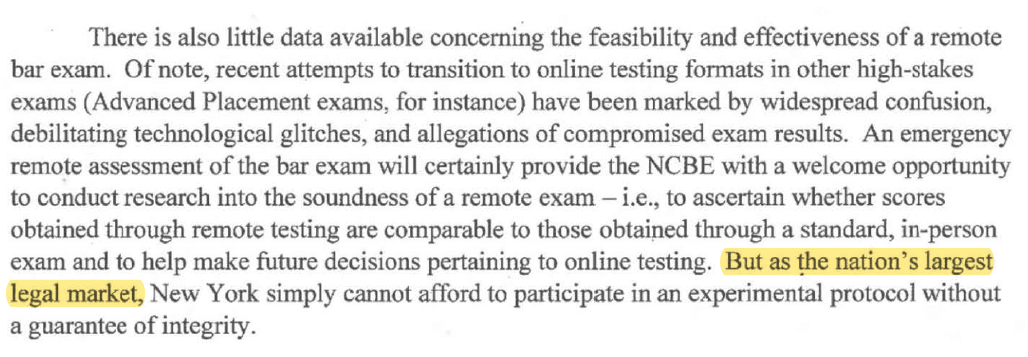

Then there’s New York. Here’s the New York Court of Appeals explaining why an online exam would not work:

“As the nation’s largest legal market . . .” I can only hear that in the voice of Thurston Howell III. Or maybe Dan Aykroyd in Trading Places, when he complains “that’s my Harvard tie!” The message seems to be that an online exam might be ok for some backwoods state, like maybe Texas, but not a civilized place like New York.

And I love the combination of arrogance and resistance to innovation. “We’re the most important legal market in the world, but using the Internet for an exam sounds way too sophisticated.” (Plus, later they changed their minds.)

In fairness, the response of the Southern states hasn’t been much better.

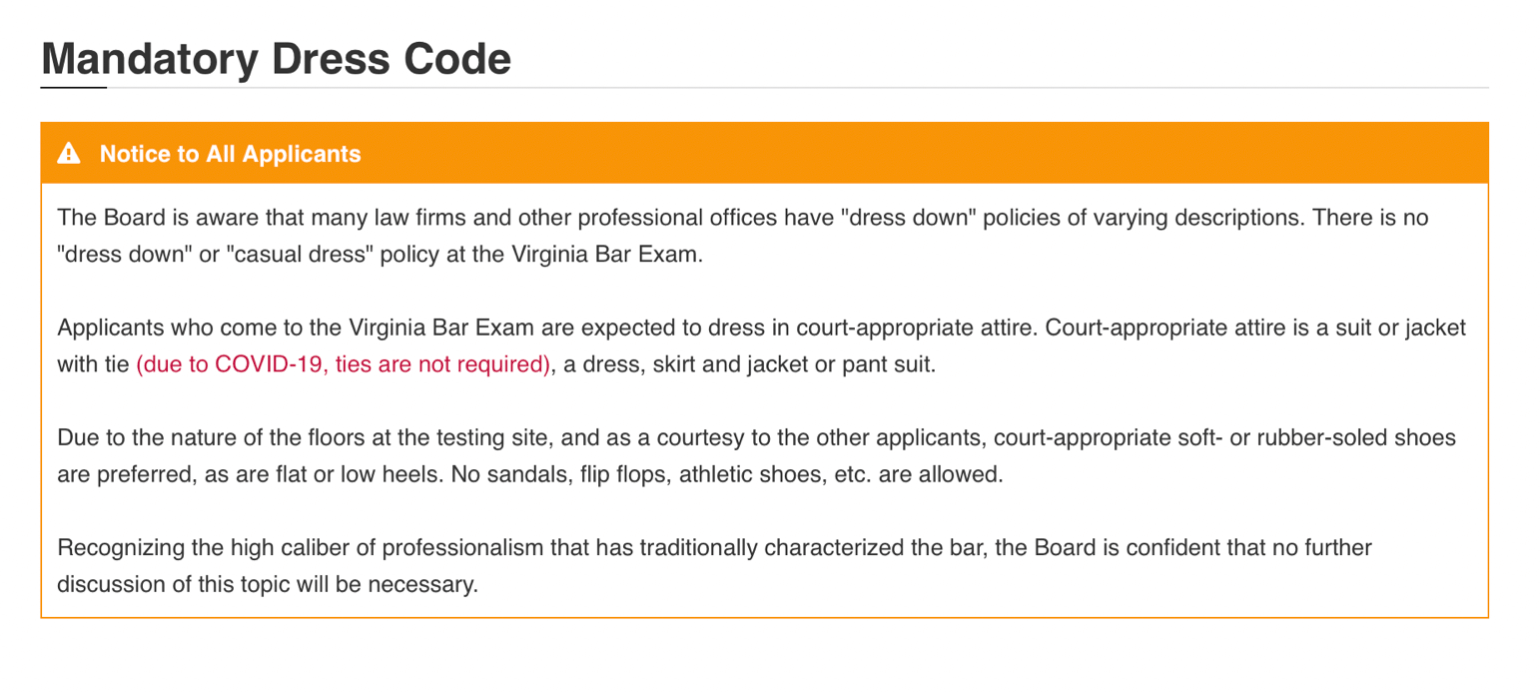

In the “bold thinking” category, Virginia responded to the unprecedented crisis with a radical change: waiving its necktie requirement. This was a big deal for the Virginia Board of Bar Examiners, which is not down with the whole “casual Fridays” thing:

This notice has such a high-school-principal-measuring-mini-skirts-with-a-ruler vibe, but without the actual concern for the students.

It also has the feel of the law firm managing partner announcing that, in lieu of bonuses this year, lawyers won’t be required to wear ties on Fridays. Wow, thanks.

And of course, “no further discussion of this topic will be necessary.”

Discouraging bar applicants from expressing dissent seems to be a theme. One prominent bar exam official said that complaints from examinees to her board were raising “character and fitness” issues.

That’s like saying “nice application to the bar you have there, it would be a shame if something happened to it.” See NCBE Prez Issues Threat To Tie Up Licenses of Bar Exam Critics.

What does it say about our profession that our response to future leaders of the bar who take the initiative to propose changes is to say, in effect, “hey, snitches get stitches”?

There also seems to be some generational prejudice at play. You get the feeling the bar examiners look at the bar applicants as “entitled” millennials who think law licenses should be handed out like participation trophies. “You want us to make special arrangements just because you could catch Coronavirus? What’s next, demanding free soy lattes during the breaks?” The collective response from bar examiners has had a tone of “just suck it up and deal.”

This was apparent in the “eye roll” incident. You can look it up.

Rolling your eyes at legitimate concerns from bar applicants strikes me as the wrong attitude. Same with dozing off during a Zoom conference with concerned bar applicants. And then there are the bar officials who suggested law school graduates who couldn’t take the bar exam and get jobs could just ask alumni for money. It’s like telling people who get evicted just to move into their summer homes.

But nothing captures the pettiness of the bar examiners quite like the anti-cheating precautions they have adopted for both in-person and online exams.

Before I get to some examples, let me be clear. Cheating on the bar exam would be wrong, and I don’t fault bar examiners for taking reasonable precautions against cheating.

But let’s be real about this. Cheating on the bar exam would be extremely difficult. You could make it an open-book exam, and it probably wouldn’t make a big difference. You’re not going to have enough time to look up the answer to each question, and looking up a rule isn’t going to help you apply the rule to a specific situation. Plus, there is no way you’re going to cram all the testable information on to some kind of crib sheet. It’s just not the kind of exam where you can write the answers on your hand.

Considering this reality, some of the anti-cheating rules bar examiners have adopted are downright bizarre.

Imagine you’re 38 weeks pregnant and taking the bar exam. Surely it would be reasonable to request a few additional bathroom breaks, right? Nope, the Illinois bar examiners said. You might have written the Rule Against Perpetuities on a roll of toilet paper in the bathroom.

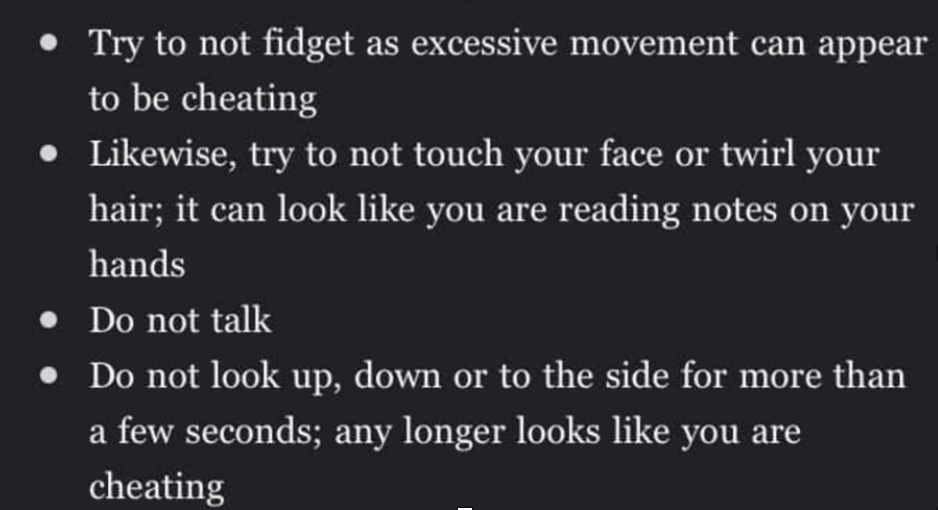

And whatever you do, don’t fidget. Consider these rules from the Tennessee Board of Law Examiners:

Seriously? Reading notes on your hand?

And the part about not looking up, down, or to the side for more than a few seconds cracks me up. It’s like the scene in This Is Spinal Tap when Christopher Guest tells Rob Reiner not to look at one of his special guitars. “Don’t touch it. Don’t point even.”

It would be funny if wasn’t so serious for the people taking the exam.

But for sheer absurdity, nothing can top the Great Tampon Caper of 2020.

It turns out that many states, including Texas where I practice, prohibit bringing menstrual products into the bar exam. I’m not making this up.

This of course raises gender equality issues. See If You’re Menstruating or Lactating During The Bar Exam You’re Screwed. Obviously, it puts a burden on women that men don’t have to worry about.

But for me, it’s even more fundamental than that. There’s something that’s just so petty and idiotic about it. Why did someone ever think this policy was a good idea? Did they think women were going to write all of the hearsay exceptions on a tampon with a Sharpie?

I mean, what is wrong with people?

Abuse of Power

Ultimately, that’s my big takeaway from all of this. There is something wrong with people. I think the abysmal way that bar examiners have responded to concerns about the COVID-19 virus points out something dark about human nature. People just can’t be trusted with power.

Give us authority over other people, even—or maybe especially—in some small sphere of life, and we just can’t help ourselves. We want to use that power. We want to lord it over other people. We get an inflated sense of the importance of our little rules, and we bristle at any suggestion that we change them.

It’s why the property clerk in The Blues Brothers makes Jake stand behind the yellow line. It’s why the driver’s license lady—who was probably a very nice person to her friends and family—did the same thing to me.

And I think it must be part of why bar examiners have dropped the ball when it comes to dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic.

p.s. The Great Tampon Caper at least had a happy ending in Texas. Kudos to Texas Supreme Court Justices Brett Busby and Eva Guzman for helping to get this policy changed. See Texas lifts tampon ban at bar exam after complaints over discriminatory policy. Maybe human nature isn’t all bad.

_____________________________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm. Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020 and 2021.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients.

Comments:

this was a joy to read! im optimistic your spot on hypotheticals may help the older crowd take out concerns more seriously

Thanks for reading!

I would just like to point out that Frank Oz also played the officer who booked Dan Akroyd’s character into jail in the movie “Trading Places.” His character in Trading Places was a nod to his character in The Blues Brothers.

I have nothing else of substance to add.

I did not realize that. I love it!

So much to love. GREAT PIECE! The snooty New York Court cracks me up. And I can’t resist sending you over here.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=1mHJImUGtAQ

Finally, perhaps they also did not want women to get a boost from the positive messages printed by the manufacturers on the Tampon wrappings! Bet you didn’t know that. “Live Fearlessly” or “Be Unstoppable.”

Thanks! Love the inspirational messages.