The Highland Capital case shows what it takes for a Texas trade secrets injunction to hold up on appeal

The Highland Capital case shows what it takes for a Texas trade secrets injunction to hold up on appeal

I previously wrote here about how not to enforce an injunction in a non-compete lawsuit. But when an employee takes your client’s confidential information or trade secrets, what evidence do you need to get an injunction in the first place?

Most lawyers can recite the buzzwords courts have used thousands of times: “imminent harm,” “irreparable injury,” “no adequate remedy at law.” But let’s face it. Courts have a hard time coherently explaining these concepts. The recent Texas case Daugherty v. Highland Capital Management is no exception.[1]

Lawyers who handle these cases should understand that imminent harm and irreparable injury mean two different things:

- “Imminent harm” means that harm is about to happen if the court doesn’t stop it. This has nothing to do with whether the harm is “irreparable.”

- “Irreparable injury” means that awarding damages would be an inadequate remedy for the harm. This has nothing to do with whether the harm is about to happen or not.

Unfortunately, courts often confuse these two requirements. For example, a court will cite evidence that a competitor is in a position to use a company’s trade secrets as establishing “irreparable injury,” when that fact actually goes to the issue of “imminent harm.”[2]

Another recurring problem is that when courts cite evidence of “irreparable injury” in a trade secrets case, they often cite evidence that is either tautological or generic. In other words, they tend to cite evidence that is either (a) true by definition or (b) recited in virtually every trade secrets case. This renders the analysis less than satisfying.

Let’s use Highland Capital as an example. The basic facts were typical: Employee signs confidentiality agreement with Employer, Employee leaves Employer, Employer sues Employee for taking Confidential Stuff.

The jury verdict, on the other hand, was a little unusual. The jury found that Employee breached the confidentiality agreement, Employer’s damages were zero dollars, and Employer’s reasonable attorneys’ fees were $2.8 million. The judge awarded Employer the attorneys’ fees plus an injunction against retaining, using, or disclosing Employer’s confidential information.

This raises important questions. First, where can I find one of these clients who will pay $2.8 million to try a confidentiality agreement case? Second, what does Highland Capital teach us about what evidence is necessary for a trade secrets injunction to hold up on appeal?

Evidence of imminent harm?

Here are six things the Highland Capital court cited as evidence of imminent harm, followed by my questions:

1. The court said there was “evidence that [Employee] took, kept, and used confidential information.”

This is evidence that the employee breached his confidentiality agreement, but is it evidence of imminent harm?

2. The court cited “demands and protracted litigation.”

Saying the litigation was “protracted” reminds me of what Nathan Arizona said when the police asked if he had any disgruntled employees. “Hell, they’re all disgruntled . . .”

3. Employer’s expert testified: “this information goes to the core of what [Employer] does as a business and what [Employer] is in terms of its value.”

This is fairly generic. Believe me, every company thinks the information the employee took “goes to the core” of the company’s value.

4. Employer’s expert: the information’s “existence away from [Employer] harms [Employer] because there’s always the possibility that it can get into general distribution . . . or to a competitor.”

This seems tautological. By definition, doesn’t the fact that someone else has the confidential information create a “possibility” that it could become public or known by a competitor?

5. Employer’s expert: the harm “may not be immediate, but the harm may occur over a long period of time.”

Doesn’t the fact that the harm may occur over a long period of time suggest it is not imminent?

6. Employer’s expert testified “I cannot quantify the total harm,” and “it may be that I can’t measure the specific relationship of these documents to that harm. . . you can’t measure things that you don’t know have occurred.” Asked if he performed “any sort of statistical analysis to try to put a number to this harm,” the expert said, “We did not and could not.”

Do these statements go to whether the harm is imminent, or whether the harm is irreparable? It seems like the court put this evidence in the wrong section of the opinion.

Evidence of irreparable injury?

As for irreparable injury, the Highland Capital court cited these key points from the testimony of Employer’s co-founder:

1. “A specific document [Employee] took and failed to return revealed [Employer]’s current and prospective investment strategies.”

In other words, Defendant misappropriated confidential information. But does that make the injury irreparable?

2. There was “[a] particular document [Employee] failed to return in which one of [Employer]’s investors was identified as well as names of our other clients and the investment objectives which are confidential.”

Again, this is evidence of misappropriation of confidential information, but how is it evidence of irreparable injury?

3. “Some of the people in the marketplace can replicate our firm strategies and our investment objectives and form competing funds with these materials like marketing materials.”

This could be evidence of imminent harm, but how does it show that the harm could not be compensated by damages?

4. “If our investors see that we don’t have enough safeguards over our confidential information they would refuse to invest with us, we would be violating our agreements with them, we would be violating the law.”

Again, this is evidence of the possibility of injury, but how does it establish irreparable injury?

5. “Putting a dollar value is almost impossible. But it’s very valuable to us. It’s very, very important.”

Now we’re getting somewhere. This goes to the issue of irreparable injury. But this testimony seems generic. Very, very generic.

Based on this testimony, the court said there was “evidence of harm that could not be quantified,” and therefore, evidence of irreparable injury.

What did we learn today?

So what do you think? Does the analysis of imminent harm and irreparable injury in Highland Capital support my point that courts often get these two requirements confused? Does it show that courts often rely on tautological or generic statements to uphold an injunction?

The more practical lesson for litigators is this: If you are trying to get an injunction for your client, offer evidence showing that the defendant is going to use or disclose the confidential information soon if an injunction is not granted (imminent harm), and that damages would be an inadequate remedy because the harm is inherently difficult to quantify (irreparable injury). Even if courts get confused, don’t mix up these concepts in your own mind.

Irreparable injury can be tricky. You need to show that quantifying the damage is inherently difficult, but without conceding that the damage is speculative. This balancing act is especially difficult when, as in Highland Capital, you are also trying to persuade the jury to award lost profits or some other form of damages.

Don’t forget to prepare your witnesses to say the right “magic words,” like “putting a dollar value on this is almost impossible” (if that’s true). But take it a step further and have your witnesses explain why quantifying the damage is difficult. Because it’s not enough to have some generic testimony to uphold the injunction on appeal. It’s also important to persuade the trial court judge to grant the injunction in the first place.

*Update: If the plaintiff goes to trial on a trade secrets claim and presents expert testimony on actual damages, there is some risk the court will say that the damages evidence shows that there is an adequate remedy at law and therefore “irreparable injury.” This seems to be what happened in Pike v. Texas EMC Mgm’t, LLC, 610 S.W.3d 763 (Tex. 2020).

_______________________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas Super Lawyer® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, 2022.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

[1] Daugherty v. Highland Capital Mgm’t, L.P., No. 05-14-01215-CV, 2016 WL 4446158 (Tex. App.—Dallas Aug. 22, 2016).

[2] For example, in Tranter, Inc. v. Liss, No. 02-13-00167-CV, 2014 WL 1257278 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth March 27, 2014, no pet.), the court said that “[a] highly trained employee’s continued breach of a noncompete agreement creates a rebuttable presumption that the employer is suffering an irreparable injury.” While the fact that an employee is competing in violation of his non-compete suggests imminent harm, it does not show that the harm is irreparable.

Comments:

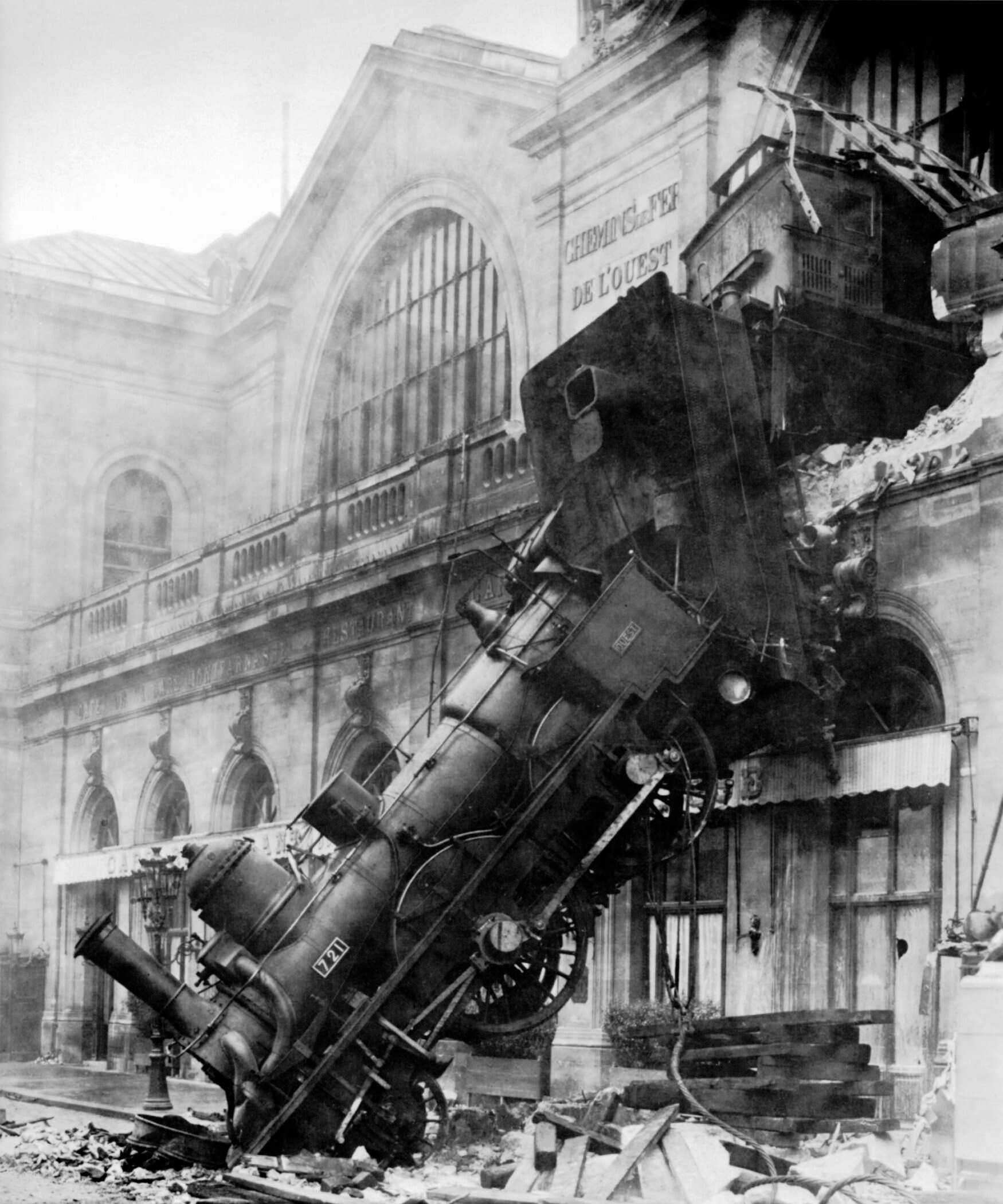

Nice posting. Nice train crash photo. I’m still pondering the difference.