One proposition that is not controversial in the law is that lower courts are bound to follow the decisions of higher courts. So, for example, an intermediate Court of Appeals in Texas must follow the precedents handed down by the Texas Supreme Court.

A more controversial topic: footnotes.

Yes, there’s a perennial, raging debate in the legal world about whether citations to case law should go in the body of a brief or in the footnotes. It gets pretty heated. Really.

I tend to side with the citations-in-the-body camp, but a recent Texas case has me rethinking the value of citing judicial opinions in the footnotes, especially when there’s an opinion that goes against my argument.

Paula Payne Gets Dawn Davis Fired

I’ll get into that later, but first let’s check in with our hypothetical friend Dawn Davis, star of many Five Minute Law fact patterns.

We last saw Dawn in Forensic Expert Fees as Actual Damages. She had left her sales job at Paula Payne Windows because she was fed up with the company sending inflated bills to customers. Now, Paula Payne’s fierce competitor Real Cheap Windows offers Dawn a job, sends her an offer letter stating her compensation, and Dawn accepts.

Let’s say Paula Payne’s lawyer hires a forensic expert to examine the laptop Dawn was using. The expert makes a shocking discovery: Dawn emailed four weekly sales reports to her personal Gmail account during her last month on the job.

Paula demands action. She tells her lawyer to put a stop to this. “But Dawn didn’t have a non-compete,” the lawyer tells Paula. “I don’t care!” Paula says. “Dawn knows all our customers, all our prices, I can’t have her working at Real Cheap.”

Paula’s lawyer calls up Chip Payne,[1] the owner of Real Cheap Windows. “Listen, Mr. Payne, I can’t tell you what to do, but we understand Dawn Davis is working for your company now, and we just found out something disturbing. Dawn has been downloading our confidential proprietary information, our trade secrets, and we just thought you should know. We are probably going to have to file a lawsuit against her.”

Next thing you know, Dawn gets a call from Chip. “Dawn, I hate to have to tell you this, but we’re going to have to let you go.” “What? Why?!” Dawn asks. “My first week of sales has been great.” “I’m sorry,” Chip says, “I really can’t get into it, we just feel like this is the best thing for our company.”

Paula Payne Windows files suit against Dawn a week later. Dawn is out of work for the next six months. She eventually finds a sales job with another company, but during that six months she drains all her savings to pay her bills and has to borrow money from her parents, retired schoolteachers.

Dawn wants justice. She asks her lawyer if she can sue Paula Payne for what it did to her. “You might have a claim for tortious interference with contract,” her lawyer says, “but I’ll have to do some research on it.” “Your employment with Real Cheap Windows was at-will, so they were free to fire you at any time, for any reason, or for no reason.”

So what’s the law on this? Does Dawn have a viable claim?

Elements of Tortious Interference with Contract

I’m going to look at Texas law, because that’s where I practice, but the same issue could come up in any state.

Let’s start with the elements of tortious interference with contract. They are:

(1) contract subject to interference

(2) willful and intentional act of interference

(3) proximate cause

(4) actual damages

Prudential Ins. Co. of Am. v. Fin. Review Servs., Inc., 29 S.W.3d 74, 77 (Tex. 2000). Even if these elements are proven, the defendant can avoid liability by proving the interference was “privileged or justified” (whatever that means). Id. at 77-78.

Do the facts of our hypothetical satisfy these elements?

It’s pretty clear that Dawn had a contract. Real Cheap made a written offer with specific terms, and Dawn accepted. We call that an offer and acceptance, a “meeting of the minds,” and it was supported by consideration, i.e. Dawn agreed to provide sales services and Real Cheap agreed to provide money. That’s a contract.

What about a willful and intentional act of interference? That goes to motive, which is usually an issue for the fact-finder to decide (i.e. the jury in a jury trial, the judge in a bench trial, the arbitrator in an arbitration).

Is there enough evidence here to raise a fact issue? Granted, we don’t have an email from Paula Payne saying “I want you to interfere with Dawn’s employment contract and get her fired!”

But the evidence of intent is hardly ever that direct. Usually it’s circumstantial. And the circumstances here are at least some evidence that Paula Payne intentionally interfered with Dawn’s employment agreement. It’s not like her lawyer accidentally called the owner of Real Cheap.

Same with causation. Let’s assume there is no evidence that Real Cheap Windows had any other reason to fire Dawn Davis. The sequence of events at least suggests that the communication from Paula Payne’s lawyer caused Real Cheap to fire Dawn. Again, it seems like at least enough to raise a fact issue.

Finally, it seems like Dawn has a pretty good case for damages. Some of you might be thinking, wait, Dawn had a duty to mitigate her damages, she couldn’t just sit around for six months doing nothing and then claim six months of salary as damages. But let’s assume there is evidence Dawn diligently looked for a new job over that six months. Again, there seems to be at least some evidence supporting the element of damages.

So there you have it. Dawn has a viable claim for tortious interference.

But of course, it’s not quite that simple. As mentioned, there is the defense of privilege or justification.

There’s also an argument that Dawn had no real contract subject to interference because her employment was at-will, i.e. that her contract was “illusory.” Can you be sued for tortiously interfering with an at-will employment contract?

Fortunately for Dawn, the Texas Supreme Court said yes, you can.

Texas Supreme Court Precedent on Tortious Interference with At-Will Employment

In Sterner v. Marathon Oil Co., 767 S.W.2d 686 (Tex. 1989), Sterner was a construction worker who filed a personal injury suit against Marathon Oil after he was injured on Marathon’s premises. Sterner got a verdict against Marathon for—imagine Dr. Evil’s voice—TWENTY-FIVE THOUSAND DOLLARS!

Later, Sterner went to work for construction contractor Ford, Bacon & Davis (FBD), which sent Sterner to work on a job at Marathon. There was evidence suggesting that Marathon got FBD to fire Sterner after learning he was on the job.

Sterner sued Marathon again, this time for tortiously interfering with his employment agreement with FBD. Id. at 688. Marathon hired a little law firm called Fulbright & Jaworski. They argued Marathon could not be liable for tortious interference, because the contract at issue was for at-will employment, which FBD was free to terminate at any time, for any reason.

But the Texas Supreme Court rejected this argument. The court held that “the terminable-at-will status of a contract is no defense to an action for tortious interference with its performance.”

Writing for the unanimous court, Justice Doggett reasoned that “[u]ntil terminated, the contract is valid and subsisting, and third persons are not free to tortiously interfere with it.” He cited the Restatement (2nd) of Torts and the “overwhelming majority of courts” on this point. Id. at 689.

Before we go on, let me inject a little context, especially for non-Texas lawyers: Justice Doggett was a liberal Democrat personal injury lawyer. Can you believe we actually had those on the Texas Supreme Court at one time? He now represents one of those weirdly-shaped Texas districts in Congress, and the Texas Supreme Court has been all Republicans for decades now. The point is that you kind of have to take a Doggett opinion from the 1980s with a grain of salt.

Still, the Texas Supreme Court hasn’t overruled Sterner (at least not explicitly), and intermediate courts of appeal in Texas have followed it.

For example, in Duncan v. Amarillo Pathological Associates, 1998 WL 889100, at *2 (Tex. App.—Amarillo Dec. 22, 1998, no pet.), the court said “[a]n at-will employment agreement can be the subject of a claim of tortious interference,” citing Sterner.

Amarillo. Keep that in mind.

Similarly, in Graham v. Mary Kay Inc., 25 S.W.3d 749 (Tex. App.––Houston [14th Dist.] 2000, pet. denied), the court said: “Graham also argues that Mary Kay’s sales agreements are ‘at-will’ contracts, and that she was acting within her legal rights in inducing Mary Kay’s beauty consultants to deal with her. We disagree. Third parties may not tortiously interfere with a contract merely because it is an at-will contract.” Id. at 754 (citing Sterner).

So that should settle it, right? Sterner is still “good law.” The at-will status of an employment agreement is no defense to a claim for tortious interference, at least not in Texas.

But here the plot thickens.

“But cf. Sterner”

In a recent case called Graves v. NAAG Pathology Labs, PC, 2021 WL 2125531 (Tex. App.—Amarillo May 25, 2021, pet. dism’d), Graves sued NAAG for causing her employer Lubbock County to fire her. The trial court dismissed the claim and ordered Graves to pay $20,000 in attorney’s fees to NAAG!

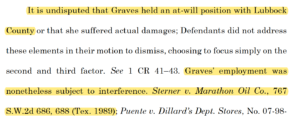

On appeal, Graves argued that her employment agreement, though at-will, was nonetheless subject to interference, citing Sterner. Here’s an excerpt from her brief:

This seemed like a solid argument supported by clear Texas Supreme Court precedent. But the Amarillo Court of Appeals took a different tack.

It focused on Texas Supreme Court cases holding that tortious interference with contract requires proof of a breach of the contract. Because Graves’ employment was at will, it was not a breach of her employment agreement for the employer to let her go, the court reasoned. Therefore, no tortious interference. Graves, 2021 WL 2125531 at *4.

Hold up. What about Sterner? As we’ve seen, in Sterner the Texas Supreme Court specifically rejected the argument that an at-will employment agreement is not subject to tortious interference.

And it wasn’t like the Court of Appeals was kept in the dark about Sterner. As we saw, Graves specifically cited Sterner in her brief.

And to the credit of the Amarillo Court of Appeals, it did not ignore Sterner. Here’s what it said:

I have to admit, part of me admires this move. There’s a Texas Supreme Court case that seems directly contrary to the rule adopted in your opinion? Just drop a footnote and put “but cf.” in front of it.

I’m going to start calling this the “But cf. Sterner” maneuver.

Maybe the pro-footnote camp was right all along.

________________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

[1] Chip happens to be Paula’s ex-husband. But that doesn’t really make a difference to the legal issues.

Leave a Comment