I kept having this recurring dream where first I was a teepee, and then I was a wigwam. Night after night, it was the same thing. First a teepee, then a wigwam. Teepee. Wigwam.

I asked my doctor about this, and he said, “I think I see the problem, you’re two tents.”

Two tents. Too tense. Get it? A teepee and . . .

Oh, never mind.

The Hotze challenge to Harris County drive-through voting

Tents are on my mind this week because of a little lawsuit that happened in my neck of the woods down here in H-Town. You might have heard about it. Less than a week before Election Day, a handful of Texas Republicans filed a lawsuit in federal court in Houston, trying to block the Harris County Clerk Chris Hollins from continuing to offer the option of “drive-through” voting.

Dr. Steven Hotze, a prominent white nationalist activist in Houston, was the lead plaintiff. You might have heard of Hotze. He’s the dude who, in the wake of the George Floyd protests, left Governor Gregg Abbott a voice mail urging him to send the National Guard into Houston to “shoot to kill” any violent rioters. “That’s the only way you restore order,” he reportedly said. “Kill ‘em.”

He sounds nice.

But I’m not going to get into the politics of the lawsuit, other than to point out that even a lot of Republicans were against it. Harris County may have gone blue, but it’s not like every one of the 127,000 drive-through voters was a Democrat. Joe Straus, the former Republican Speaker of the Texas House, even joined an amicus brief in support of the Harris County Clerk.

No, I just want to focus on one of the narrow legal issues in the case, and what it teaches us about the theory of adjudication known as “textualism.”

The legal issue, in a nutshell, was whether a tent is a “building.”

See, the Hotze plaintiffs argued that the use of temporary tents for voting violated the Texas Election Code, which provides for voting in a “building.” They asked the court to enter an injunction against further drive-through voting and to “reject” the 127,000 drive-through ballots already cast. They filed the federal lawsuit on October 28, shortly after the all-Republican Texas Supreme Court rebuffed their bid to obtain similar relief in Texas state court.

The case was assigned to U.S. District Judge Andrew Hanen. This caused Democrats a little discomfort, considering some press reports characterizing Judge Hanen as a highly partisan Republican appointee.

I did not share their concern. I made this prediction on Twitter:

I just knew a federal judge was not about to tell 127,000 Houstonians “sorry, the County Clerk messed up, so your votes just don’t count.”

And I was right. Judge Hanen denied the request to “reject” the drive-through votes already cast. In fact, he dismissed the whole lawsuit on the procedural ground of lack of standing.

(There were several strong procedural grounds for rejecting the request for an injunction, including the plaintiffs’ delay in seeking relief and the fact that, even when there is a violation of the Election Code, “rejecting” votes is rarely the warranted remedy.)

But just to cover his bases—knowing the ruling would be appealed—Judge Hanen issued an order stating how he would have ruled if the plaintiffs had standing. And he said he would have sided with the Hotze plaintiffs on at least one issue: a tent is not a “building.” He cited dictionary definition of “building” to support this conclusion. Thus, he applied the theory of textualism to decide the issue.

And that was the most interesting part of the case to me.

Another Test Case for Textualism

My loyal Fivers already know about my interest in textualism. I wrote about it in Bostock Opinion Shows That Strict Textualism Fails to Deliver on its Central Promise.

My thesis: In Bostock, the phrase “because of sex” was ambiguous as applied, i.e. subject to more than one reasonable interpretation, so the application of strict textualism did not yield one determinate answer, contrary to the textualist arguments offered by both the majority and the dissenters.

For me, the lesson of Bostock was that strict textualism failed to deliver on its central promise of determinacy and legitimacy. The text of the statute by itself just wasn’t enough; the Court had to look to something else to decide the question, even if it pretended like it didn’t. Not only did textualism fail to deliver on its promise, I wrote, it failed spectacularly.

But maybe the Hotze case would give textualism a chance to redeem itself.

Perhaps it was unfair to treat Bostock as a test case. You could not get a more “hot button” political issue than the question in Bostock: whether federal law prohibits discrimination against homosexual and trans-sexual employees. You might argue it’s going to be hard to find any neutral theory of adjudication that’s going to satisfy everyone on such an issue.

Maybe textualism would fare better when the issue was less incendiary, mundane even.

Granted, the issue came up in the context of a hotly contested presidential election. But the issue itself had hardly any political valence. It’s not like there’s a “liberal” or “conservative” position in the abstract on whether a tent is a building. Ask some of your friends and family. Unless they’re familiar with the issue in the Hotze case, it’s not like all the MAGA people are going to say one thing and all the libs the opposite.

Just like there’s no “Republican” or “Democrat” position on whether Batman is a superhero. (Or is there?)

Anyway, the point is that when the legal issue isn’t a contested battle in the culture wars, you might expect textualism to do a better job of delivering on its central promise. So let’s see how it did in Hotze.

Application of Textualism in Hotze v. Hollins

The first thing we find when we look closer at Hotze is that the statutory interpretation question was slightly more complicated than we thought. It turns out there were two different statutory sections at issue in Hotze, one for early voting, and another for Election Day voting.

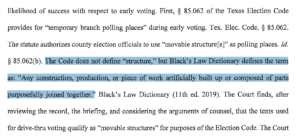

As for the early voting statute, the Hotze plaintiffs just didn’t have a strong argument. The statute on early voting referred to a “movable structure” rather than a “building.” This is an issue where textualism is probably adequate. I just don’t see a reasonable argument that a tent is not a “movable structure.”

Judge Hanen didn’t either. To decide whether a tent is a structure, he looked to Black’s Law Dictionary:

Applying the dictionary definition, Judge Hanen found that a tent was a structure. Thus, he did not think that the use of drive-through tents for early voting violated the statute.

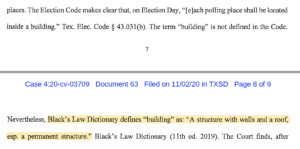

But the section on Election Day voting was different. It provided that each polling place on Election day “shall be located inside a building.” Tex. Elec. Code § 43.031(b). Most people would probably agree a tent is a “movable structure,” but is it a “building”?

Let’s pause here and just reflect on the fact that there are different ways you could approach this question. Before textualism became fashionable, I think most Texas judges—liberal or conservative—would have approached the issue pragmatically. “I don’t see anything wrong with drive-through voting, so sure, for this purpose I can say a tent is a building” would be the typical thought process.

But the Harris County Clerk, probably considering the audience, took a different approach, the textualist approach. This applies the “plain meaning” of a statute’s words, and as a recent textualist opinion in Texas said, “[d]etermining a word’s plain meaning is a dictionary-driven process.” Kawcak v. Antero Resources Corp., 582 S.W.3d 566, 573 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth 2019, pet. denied).

So, notably, both the lawyers for Hollins and Judge Hanen looked to Black’s Law Dictionary for the meaning of “building.”

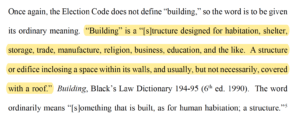

Here are excerpts from the brief filed by Hollins (top) and Judge Hanen’s order (bottom):

Notice any discrepancy?

Yes, of course. They cite different editions of Black’s Law Dictionary that have slightly different definitions.

I think this exercise in dueling dictionaries teaches us some things about “dictionary-driven” textualism.

Textualism fails to deliver determinacy, again

First, and perhaps most obvious, dictionaries will have multiple definitions of a word, and different dictionaries will define words differently. This is a problem for textualists, but one they are aware of. In the Kawcak opinion, for example, the court painstakingly parsed multiple definitions of the word “common” from three different dictionaries, even getting down into the order of the different definitions.

The problem is that multiple definitions and multiple dictionaries can create ambiguity. If one definition leads to one result and another definition leads to the opposite result, then the dictionary exercise doesn’t answer the question.

And that seems to be exactly what happened in Hotze. The only thing the dueling definitions seemed to agree on is that a building has walls.

But it was even worse than that. Not only were the two dictionary definitions of “building” different, neither definition definitively answered whether a tent is a building.

The definition cited by Hollins focused on the purpose of a building, i.e. what it is designed for, but none of the examples it cited included voting. So you could argue it either way.

Same for the definition cited by Judge Hanen. That definition said “especially a permanent structure,” but it didn’t say a building has to be permanent. So again, you could make a reasonable argument either way.

This is a problem. If the point of dictionary-driven textualism is to apply an objective method of statutory interpretation that provides a single determinate answer, then it failed in Hotze, just like it failed in Bostock.

But even aside from the determinacy problem, which I explained in the Bostock post, I think the Hotze example shows how misguided the whole dictionary-driven enterprise is in the first place.

The problem with “dictionary-driven” textualism

The basic problem is the nature of language itself. Most words, even simple ones like “common” or “building,” are inherently fuzzy. When the authors of Black’s Law Dictionary—or any dictionary—try to define a word like “building,” they are just trying to capture the gist of the meaning. Their purpose is not to draw sharp lines between what things the definition embraces and what things it doesn’t.

In other words, when the authors of Black’s Law Dictionary wrote a definition of “building,” they were not thinking about defining the word in a way that would determine whether a tent is a building. If they had been thinking about that question, they might have drafted the definitions differently.

For this reason, the dictionary approach strikes me as misguided from the start, even before we get to the indeterminacy problem. It’s like looking at a dictionary to determine if a hot dog is a “sandwich.”

Granted, there is precedent for this approach. When Stephen Colbert asked Ruth Bader Ginsburg whether a hot dog is a sandwich, she gave a classic textualist answer her late friend Antonin Scalia would have loved: “you tell me what a sandwich is, and then I’ll tell you if a hot dog is a sandwich.”

With much respect for the late great Notorious RBG, I think that’s the wrong approach.

Here’s the thing. We all know what a “sandwich” is; we don’t need to look at a dictionary. The problem is that in some ways a hot dog is like the things that we all agree are sandwiches, and in other ways it is not. So, even if the dictionary definition of “sandwich” provides a single determinate answer, the dictionary exercise just doesn’t seem that valuable to me. The authors of the dictionary wrote the definition for a general purpose, not for the purpose of either including or excluding a hot dog.

(There is actually some legal precedent about whether a hot dog is a sandwich, as one of my son’s favorite YouTubers explains in Food Theory: What Makes a Sandwich a Sandwich?)

If dictionary-driven textualism is all wrong for the internet parlor game of asking whether a hot dog is a sandwich, then surely it is even more misguided for serious questions of justice and public policy.

Judges aren’t playing some game of Scrabble. They are deciding real disputes that have serious consequences for the parties. And in some cases, like the Hotze lawsuit, they are deciding issues that impact major matters of public concern. Do we really want such momentous decisions to turn on some kind of word game?

No, playing the dictionary game is not how they should do it.

I’m not saying dictionary definitions are totally irrelevant. But framing the question as “is a tent a building?” strikes me as looking through the wrong end of the telescope. The question should not be whether a tent is a building in the abstract, but whether for the purpose of this particular statute, in this particular dispute, the court should construe “building” to include a tent, considering the consequences of the decision and the special circumstances, i.e. the COVID-19 pandemic.

When you frame the question that way, it practically answers itself.

We’ve got you surrounded, textualism

But don’t take my word for it. I’m not the only one who says judges should look to the purpose of a disputed term, the surrounding circumstances, and the consequences of a particular construction.

For one thing, you can find support for my view in Texas contract law. The Texas Supreme Court has recognized that “surrounding circumstances” can bear on the meaning of a contractual term, even when the term is not ambiguous on its face. See Nat’l Union Fire Ins. Co. v. CBI Indus., Inc., 907 S.W.2d 517, 521-22 (Tex. 1995).

I think this contract principle provides an important lesson for statutory interpretation.

In theory, it’s fine to say that courts should apply the plain meaning of an unambiguous statutory term, without looking to extrinsic evidence. But to determine whether a term is ambiguous, we must first ask if it has more than one reasonable interpretation, and it’s hard to say if an interpretation is reasonable without looking to the surrounding circumstances. See CBI Industries, 907 S.W.2d at 521 (“The ambiguity must become evidence when the contract is read in context of the surrounding circumstances”). That’s why contract law allows judges to look at surrounding circumstances.

Now let’s apply that idea to the election statute.

Suppose there was an election where drive-through voting on Election Day resulted in numerous problems, leading to a public outcry and demand for reform. As a result, a state representative sponsored legislation to require all voting to take place “inside a building,” with the aim of putting a stop to drive-through voting in future elections.

That’s not what actually happened. There’s no indication that the definition of “building” in the Texas Election Code had anything to do with tents. The section at issue is mainly concerned with distinguishing between public and non-public buildings and addressing what kind of non-public buildings can be used. The provision requiring voting in a “building” seems incidental to that other purpose.

But what if the definition of “building” did result from the hypothetical public outcry described above. Wouldn’t that surrounding circumstance have some bearing on whether construing building to include a tent was a reasonable construction or not? Wouldn’t that be the most logical place to start?

But the strict textualist says no, unless the undefined statutory term is ambiguous, you look to the dictionaries and no further.

Ok, but let’s consider another hypothetical. Imagine the legislature itself, while not providing a definition of “building,” did provide express guidance to the courts on how to interpret the statute.

Let’s say the legislature, rather than restricting judges to the dictionary definition of a statutory term, instructed judges that when construing a statute they can look to the purpose of the statute, the circumstances surrounding its enactment, the legislative history, and the consequences of a particular construction, even if the statute is not ambiguous. In other words, suppose the legislature expressly told courts they are not required to apply strict textualism.

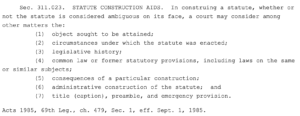

What if I told you that is exactly what the Texas legislature did? Here is Section 311.023 of the Texas Code Construction Act:

As you can see, the legislature has invited Texas courts to consider extrinsic sources when construing a statute, even when the statute is not ambiguous.

But Judge Hanen’s order in the Hotze case said nothing about Section 311.023. He didn’t look at the purpose of the statutory provision or its surrounding circumstances. Instead, he just quoted from one of the Black’s Law Dictionary definitions and then said a tent isn’t a building. Was this a mistake?

The Tex-tualists strike back

To be fair, Hollins did not argue Section 311.023. Plus, the Texas Supreme Court has expressly declined the legislature’s invitation in Section 311.023 to consider extrinsic factors to construe a statute. See Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital of Denton v. D.A., 569 S.W.3d 126, 136 (Tex. 2018).

Texas Health was a medical malpractice case involving a classic statutory interpretation problem: whether a modifying phrase at the end of a clause applies to all the terms of the clause, or only the last term.

The statutory clause at issue was: “in a hospital emergency department or obstetrical unit or in a surgical suite immediately following the evaluation or treatment of a patient in a hospital emergency department.” The question was whether “following the evaluation or treatment of a patient in a hospital emergency department” applied to “in a hospital emergency department.” The outcome of the case turned on this question.

The plaintiffs urged the court to consider extrinsic evidence, including legislative history, citing Section 311.023. But the Texas Supreme Court refused. “Although this section may grant us legal permission,” Justice Boyd wrote, “not all that is lawful is beneficial.” Id. at 136.

Instead, Texas Health cited Scalia & Garner’s Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts (available to Amazon Prime members for $47.45), a book that is big on textualism and kind of down on legislative history, to put it mildly. Finding the statute unambiguous, the court refused to consider any extrinsic aids to interpreting it.

That’s not how I would have done it. I might have reached the same result in Texas Health, but more on common sense grounds than textualist grounds.

And I have to say, I’m bothered that the Texas Supreme Court gave more weight to a privately-authored treatise—which only expresses the opinion of its authors—than it did to the legislature. That’s a strange sort of deference, and I don’t like it.

But maybe I’m just too tense.

______________________________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer” for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

Comments:

Excellent post. A fun exploration into the essence of what lawyers must do; i.e. determine not just a law but the parts of it – the individual word. I am curious about a a different shading often used by textualists, the idea of originalism. Could which dictionary to use turn on the one, such as Black’s, that stood at the time the law was drafted? This could certainly comply with 311.023(2) about considering the surrounding circumstances under which the statute was drafted. I see that as an argument though I really don’t like rigid allegiance to. such ideas as textualism or originalism when we are dealing with fundamental elements of our democracy.

Thanks, Stanley! Yes, I think looking to dictionaries at the time of enactment would be consistent with orginalism. But in this case at least, it strikes me as not a useful exercise. It’s not like the meaning of “building” has changed in some fundamental way over the years, such that people once thought a tent was a building but don’t anymore, or vice versa.