What if I told you that to understand an employee’s confidentiality duties, you need to understand there are three kinds of confidential information covered by at least four different areas of law?

You see, employers have three kinds of confidential information:

- Trade secrets

- Confidential information that is not a trade secret

- “Confidential” information that is not actually confidential

A trade secret is confidential information that has “independent economic value” and is “not readily ascertainable” by competitors. Secret technology, secret business plans, the literal secret sauce—these are obvious trade secrets. Less obvious things like customer lists and company prices can be trade secrets if they have independent economic value and are not readily ascertainable. In other words, you can tell that information is a trade secret if obtaining the information gives a company a competitive advantage.[1]

A typical employer is going to have a lot of confidential information that is not a trade secret. For example, a social security number or other personal identifying information of an employee is highly confidential. Same for an employee’s personal healthcare history. But information like that is typically not going to give the company any competitive advantage.

Of course, employees learn all kinds of information about the company that is not confidential at all. People outside the company may not know how to get to the company cafeteria, but that information isn’t really confidential. (Think Tom Cruise pointing out that the location of the mess hall is not in the Marine manual in A Few Good Men.)

So why do I include non-confidential information in the list of types of confidential information? Because many companies define virtually all company information as “confidential” in their employment agreements or employee policies. I’ve seen a lot of employment agreements like this, and you’ve probably seen the same thing.

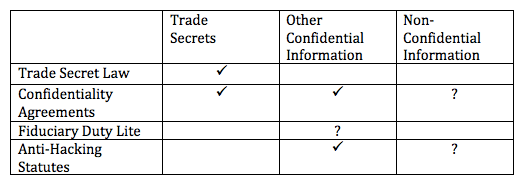

So what does the law say about an employee using these three types of confidential information after leaving the company? There are four key areas of law that govern an employee’s duties concerning confidential information.[2]

Four areas of law. Three types of information. I feel a matrix coming.

And here it is. This chart shows which areas of law cover which types of information:

Don’t worry, I’ll explain.

Trade Secrets Law

Most states, like Texas where I practice, have some version of the Uniform Trade Secrets Act, affectionately known as UTSA. Then there is a federal statutory overlay called the Defend Trade Secrets Act (DTSA). These statutes provide civil remedies for “misappropriation” of trade secrets, including injunctions, actual damages, and, in some cases, punitive damages and attorneys’ fees. See Trade Secrets 101.

But the trade secrets statutes do not apply to misappropriation of confidential information that is not a trade secret. And whether the information at issue is actually a trade secret is often a major point of contention. So employers don’t want to limit themselves to protecting trade secrets.

Confidentiality Agreements

Enter the confidentiality agreement. Almost every employment agreement is going to have some kind of confidentiality clause. And while the definitions of confidential information vary, the tendency is to define confidential information very broadly. As a result, most confidentiality agreements are not limited to trade secrets.

Heck, most confidentiality agreements are not even limited to confidential information. And thus the question mark in the “Non-Confidential Information” column above. Is it really a breach if the employee uses or discloses information that is not actually confidential?

To make this less abstract, let’s say while working for Paula Payne Windows, Dawn Davis learns the name and phone number of the right person to contact at a window manufacturer to check prices and place orders. Dawn quits and goes to work for Real Cheap Windows. Does she violate her agreement if she uses her knowledge to place a call to the guy she knows at the window manufacturer?

This may be a technical breach, but it is unlikely to give Paula Payne a solid claim for damages, for at least two reasons.

First, it would be hard for Paula Payne to prove that the breach caused damages, especially if Dawn Davis could have found the same person simply by calling up the manufacturer and asking who to talk to. (It would become more complicated if the agreement also has a liquidated damages clause.)

Second, defining confidential information to include virtually everything is arguably an illegal restraint of trade or commerce. It is a restraint of trade because, if applied literally, it would effectively prevent an employee from doing anything in the same industry after leaving the company.

So, disclosure of non-confidential information probably isn’t an actionable breach of a confidentiality agreement. But it’s still a question mark.

Fiduciary Duty Lite

Fiduciary Duty Lite is the term I use for the limited kind of “fiduciary” duty that employees owe employers. An employee’s Fiduciary Duty Lite includes a duty not to use the employer’s confidential information or trade secrets in competition with the employer.

So why no check mark for Fiduciary Duty Lite under the Trade Secrets column? In a word: preemption. The Texas Uniform Trade Secrets Act expressly states that it displaces any conflicting law providing civil remedies for misappropriation of a trade secret.[3] Texas courts have interpreted this to mean that TUTSA preempts a breach of fiduciary duty claim that is based on alleged misappropriation of a trade secret.[4] Thus, no check mark.

But what about a breach of fiduciary duty claim that is based on an employee’s use of confidential information that is not a trade secret? Does the trade secrets statute displace that claim?

Courts are split on this question. The “majority” rule seems to be that the trade secrets statute preempts this type of claim, even though the claim does not require proof of a trade secret.[5]

This rule should bother advocates of textualism. The plain language of the trade secrets statute says it displaces “conflicting” law providing civil remedies for misappropriation of a trade secret. A claim for breach of Fiduciary Duty Lite that is based on information that is not a trade secret does not conflict with the statute.

But I get it. The rationale is that allowing an employer to characterize what is really a trade secrets claim as a claim for breach of fiduciary duty would conflict with the preemptive purpose of the trade secrets statute.

Anti-Hacking Statutes

The relevant statutes are not limited to trade secrets. Consider also the federal anti-hacking statute, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA).[6] The Texas version is the Breach of Computer Security and Harmful Access by Computer Act (HACA).[7]

I would summarize these statutes, but I really can’t improve on the article here by Texas lawyer and cybersecurity expert Shawn Tuma. Bottom line: these statutes prohibit “unauthorized access” to computers and provide civil remedies for knowing and intentional violations.

I will use the HACA as an example. If a company hacks into a competitor’s server and steals confidential information, that is an obvious violation. But the HACA is not limited to hacking by outsiders. An insider who accesses the company computer system for an improper purpose or exceeds the scope of his authorized access can also violate the statute, because the statute prohibits access without the company’s “effective consent.”

The picture gets fuzzier when an employee’s access was authorized at the time. Let’s take the typical departing employee scenario where an employee legitimately obtains confidential information from the employer’s computer system in the course of employment for a legitimate purpose, but the employee later misuses the information for the improper purpose of competing with the employer. Whether that conduct violates the statute is a more difficult question.

(Update: the U.S. Supreme Court construed CFAA narrowly in Van Buren v. United States.)

Another tricky question is whether the employer could have a claim under the anti-hacking statute for an employee obtaining non-confidential information from the company’s computer system. The HACA is not limited to confidential information, but it does require proof of “damages as a result” of the unauthorized access, i.e. causation. As with confidentiality agreements, it may be difficult to prove a violation caused damages if the accessed information was not really confidential.

Oh, one more thing just to add another layer of complexity. As with fiduciary duty, a claim under the anti-hacking statute that is based on misappropriation of trade secrets is preempted by the trade secrets statute.[8]

Are we clear?

__________________

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

[1] The words “competitive advantage” don’t appear in the statutes that now define trade secrets in most states and under federal law, but you see the phrase in the common-law case law, e.g. In re Bass, 113 S.W.3d 735, 739 (Tex. 2003), and it is useful for understanding what is and is not a trade secret.

[2] I can’t wait for one of my Fivers to point out I have left out some crucial additional source of employee confidentiality duties, like HIPPA.

[3] Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code § 134A.007(a). But note the statute does not preempt a breach of contract claim.

[4] E.g. Super Starr Int’l, LLC v. Fresh Tex Produce, LLC, 531 S.W.3d 829, 843 (Tex. App.—Corpus Christi 2017, no pet.).

[5] See discussion in Embarcadero Technologies, Inc. v. Redgate Software, Inc., No. 1:17-cv-444-RP, 2018 WL 315753, at *2-4 (W.D. Tex. Jan. 5, 2018). In StoneCoat of Texas, LLC v. ProCal Stone Design, LLC, 426 F. Supp. 3d 311, 333-39 (E.D. Tex. 2019), the court discussed Super Starr, Emabarcadero, and other cases. It held that claims for conversion, tortious interference, and tortious interference were preempted where they all stemmed from alleged taking of plaintiffs’ confidential information, even if not all of the information was trade secrets.

[6] 18 U.S.C. § 1030.

[7] Tex. Penal Code § 33.02; Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code § 143.001.

[8] Embarcadero, 2018 WL 315753 at *5.

Leave a Comment