On February 1, 2017, a jury in a Dallas federal court returned a verdict in ZeniMax v. Oculus, a high-stakes battle over who owns the technology used in the Oculus Rift virtual reality system. The jury found that Oculus and its co-founders caused damages totaling $500 million. That’s a lot of money in some circles, but the COO of Oculus’s owner said “the verdict is non-material to our business.”

You see, the owner of Oculus is a little company called Facebook.

But still, it’s not every day that a Texas jury finds damages of half a billion dollars in a case involving allegations of trade secret misappropriation, copyright infringement, breach of a non-disclosure agreement, trademark infringement, and spoliation of evidence. As a Texas litigator who deals with all of these issues, I was curious to see what lessons could be learned from the Oculus verdict.

The answer: not a whole lot. The problem is that you can read every word of the 90-page jury verdict and still have no idea what happened in the trial. And news reports about the verdict don’t add much. In fact, the Oculus case is a prime example study of how little the typical press coverage of a jury verdict tells you.

Of course, you can at least learn who the main players were:

- Video game pioneer John Carmack worked for id Software, a subsidiary of ZeniMax.

- Carmack came into contact with wiz kid Palmer Luckey, who was developing a virtual reality headset called the Rift.

- Luckey founded Oculus to commercialize the Rift.

- Carmack worked with Luckey on improving the Rift.

- ZeniMax entered into a Non-Disclosure Agreement with Luckey and Oculus.

- Carmack eventually left id Software and joined Oculus.

- Brendan Iribe was the CEO of Oculus.

- Facebook bought Oculus for $2 billion.

ZeniMax and id Software sued Carmack, Luckey, Iribe, Oculus, and Facebook, claiming they misappropriated trade secrets and other intellectual property.

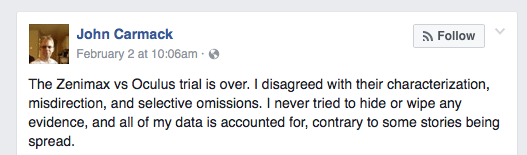

For me, the most interesting nugget was ZeniMax accusing Carmack of stealing documents on a USB drive and wiping his computer to destroy evidence. Carmack denied these allegations in a Facebook post after the verdict, saying “I never tried to hide or wipe any evidence,” but if the jury heard evidence supporting these allegations, it must have colored their perception of other issues in the case.

The defendants were able to claim a partial victory because the jury found that none of the defendants misappropriated ZeniMax’s trade secrets. But the jury found liability on other causes of action, and significant damages, against all defendants except Facebook:

- $50 million against Oculus for copyright infringement

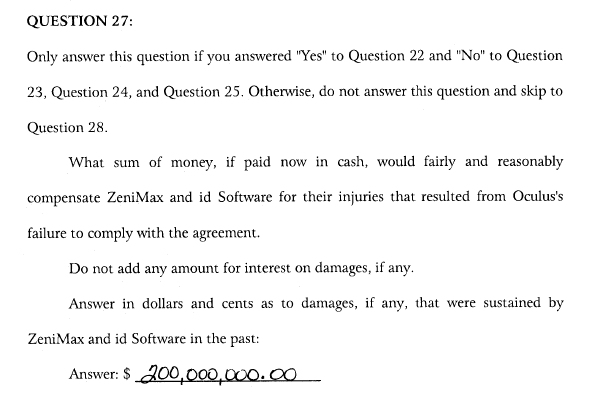

- $200 million against Oculus for breach of the Non-Disclosure Agreement

- $50 million against Oculus for false designation of origin

- $50 million against Luckey for false designation of origin

- $150 million against Iribe for false designation of origin

Add these up, and you get a headline like this: “Oculus lawsuit ends with half billion dollar judgment awarded to ZeniMax.” If you’re a litigator, that kind of headline makes you cringe. Not because of the amount of money, but because you know that a jury doesn’t award a “judgment” at all. The jury renders a verdict. Later, the judge enters a judgment based on the verdict.

Maybe it sounds nit-picky, but reporters make this mistake all the time. When a headline says “Oculus ordered to pay $500 million in ZeniMax lawsuit,” it is simply inaccurate. The jury doesn’t order anyone to pay anything. The jury just fills in a blank in response to a question. The judge decides whether to order the defendant to pay.

The distinction can be important. In some cases, entering a judgment on the verdict is a routine, almost ministerial, act by the judge. But in any moderately complex case, you can bet there will be a battle of post-verdict motions over what to do with the verdict. This is the trial court judge’s opportunity to rule on legal issues in the case before it goes up on appeal.

It’s possible that the judge in the Oculus case will simply render judgment ordering each defendant to pay the amount of damages the jury found that defendant caused, but I don’t expect it will be that simple. (Narrator: it would not be that simple.) You can look at the complicated charge and the number of high-priced lawyers on the case and know there is going to be a battle over the judgment.

Expect the defendants to argue that there was insufficient evidence to support the jury’s answers on both liability and damages. I also wonder if there is an election of remedies issue. When the jury awards damages on several causes of action that arise from the same facts, the judge doesn’t necessarily add up all the dollar amounts and award the total to the plaintiff.

So the verdict is the climax, not the end of the story. We’ll have to wait and see whether the judgment actually awards $500 million (plus interest and maybe attorneys’ fees?), and whether the judge grants an injunction against sales of the Oculus Rift based on the jury’s finding of copyright infringement.

I tried to think of a good football analogy, but golf is better for this point. Discovery and pre-trial motions are the first 17 holes. The trial is getting the ball on the 18th green. The post-verdict motions and appeals are getting the ball in the hole to win the tournament. That’s why they say “trial lawyers drive for show, appellate lawyers putt for dough.”

It will be fun to watch ZeniMax’s lawyers putt for $500 million.

*Update: The trial court later cut the amount of damages in half, an appeal to the Fifth Circuit was filed, and the parties eventually settled before the appeal was decided.

The trial court held a hearing on post-verdict motions on June 20, 2017 (see transcript here). In an opinion and order issued on June 27, 2018, Judge Ed Kinkeade, agreed that there was no evidence of any actual damages to Zenimax caused by the unauthorized use of Zenimax’s marks. Zenimax’s damages expert had only testified to damages caused by the alleged misappropriation of trade secrets, and there was no evidence tying any of the $2 billion Facebook paid for Oculus to any act of false designation. Zenimax Media Inc. v. Oculus VR LLC, No. 3:14-CV-18490K, 2018 WL 3135915 (N.D. Tex. June 27, 2018). The trial court entered judgment for $250 million against Oculus, and Oculus filed a notice of appeal.

As reported here by The Verge, the parties later signed a confidential settlement agreement in December 2018. “While we dislike litigation,” ZeniMax CEO Robert Altman reportedly said, “we will always vigorously defend against any infringement of misappropriation of our intellectual property.”

Wait, dislike litigation? What’s not to like?

___________________

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

Leave a Comment