I had big plans for my one-year solo law practice anniversary, which came on August 16, 2022. I had the perfect blog post planned to coincide with it.

Unfortunately, I was too busy with client work to write the blog post in time.

And that kind of tells you how the first year of Zach Wolfe Law Firm 2.0 went. Business development was largely a success. I mean, it could always be better, but I had no shortage of paying client work to do. The only problem I really had was keeping up with all the work.

More about that later.

Now that I’ve had a chance to catch up, I’m going to share the lessons I’ve learned from one year of solo law practice. With a little help from my Twitter friends.

If you happened to see my presentation at the 2022 Texas State Bar Annual Meeting, these lessons may sound familiar.

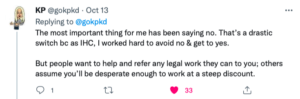

I will also confess that you can find better tips just by following @gokpkd on Twitter.

Spoiler alert: I think you’ll find these lessons apply to any kind of law practice, not just a solo firm.

Do you need traditional office space?

Lesson 1 is that you don’t necessarily need traditional office space.

I had a few options on this front: lease some traditional office space, lease an office at an “office suites” kind of place (like Regus), get a “virtual” office through the same kind of office suites arrangement, etc.

I settled on sharing office space with a firm I knew. To be honest, I hardly ever go there. The main thing I like about it is having a conference room available for meetings and depositions. But even that I’ve rarely needed (partly because of Covid and Zoom).

The bottom line is to think about what you really need your office space for. Don’t just assume you have to spend the money on traditional office space.

Do you have some type of “consumer” practice where you represent a lot of ordinary people? A respectable “brick and mortar” office may help establish credibility and give you a place to meet with them. Or maybe you need a place where your staff can work.

Are you targeting high-end corporate clients and need to project a certain image with a premium downtown office address? Then it may be worth the money to pay for that.

Just don’t spend the money on that sort of thing if you really don’t need to. For example, let’s say you represent big corporations but they are spread all over the country. You might choose to office at home because your clients never come to your office anyway. I know there are people who do this.

WFH?

This brings up a related point. Lesson 1a is that whatever you decide to do about office space, you don’t necessarily need to actually work there.

Because of Covid, we’ve all learned that remote work can work pretty well. There are of course pros and cons. A thousand other articles have covered that issue, so I won’t belabor it. I’ll just urge you to consider how much time you can save if you don’t have to commute.

But if there are other reasons it helps for you to work at your office, then go for it. Just don’t feel like you have to do it because that’s just the way it has always been done.

Do you need employees?

Lesson 2 is that you don’t necessarily need employees.

This is very much analogous to Lesson 1. There are some good reasons to hire employees. Just don’t assume you need to do it to have a successful law practice. In my first year of solo practice, I had no employees, just a part-time contract legal assistant and some help from a law student clerk.

This brings up a related question: whether you hire traditional employees or not, as a solo lawyer should you pay people to do stuff for you?

Should you pay people to do stuff for you?

That brings up lesson 3.

Some will say that you should outsource every task that you can, so that you spend as much of your time as possible only on the things that really require you to do them. These are the things you are best at, and include the things you can bill clients for.

I definitely see the logic in that. I started paying a company to mow my grass. Sure, it was a little pricey, but if I could bill an hour to a client during that time, it would more than pay for it.

Still, I wouldn’t go as far as saying you should always pay people to do stuff for you. It really depends on where you are in your solo practice journey.

Specifically, how much paying client work do you have?

If your amount of billable client work is about 90% of your capacity or above, then it makes more sense to pay people to do things. Because if you spend time on them, it will probably cut into time you could be billing.

On the other hand, if you’re at 50% capacity or less on paying client work and just trying to keep the lights on, then it might make more sense for you to make that trip to the FedEx store yourself. Just be careful that your unpaid administrative tasks don’t cut in too much to your business development time.

Personally, I could probably stand to outsource a little more, but I’m working on that.

Should you take any work that “comes in the door”?

Lesson 3a applies the same logic to the perennial question of whether a lawyer should take any client work that “comes in the door.”

Some people will dogmatically say you should only take work that is in your specialty, and I understand the rationale for that, but again, I think that’s a little too strong.

Like the question about paying people to do stuff, I think it depends on where you are in your business development journey.

Now, let’s be clear about one thing: you should never take a matter that you don’t have the competence to handle. Not only is that bad for business, it could be an ethical violation.

The harder question is when a potential client has a matter you are capable of handling effectively, but it isn’t really in the niche you’re trying to develop.

In that case, I say again that it depends on how much client work you’re already generating.

If you’re struggling just to make payroll next month, then you should probably take that paying work you’re qualified to handle, even if it isn’t exactly the kind of work you want.

A related concept: think about specializing in the work you’re already getting. See Are you stumbling on gold bricks in your search for copper deposits.

On the other hand, if you are already covered up with client work in your specialty, you are probably better off sending that assignment to someone else.

I’ll give you a concrete example.

Because I do a lot of work representing employees who have non-competes, people often contact me about other kinds of employment matters, like harassment or discrimination. I know enough about that kind of case that I could take it, but I have decided to refer those cases to other lawyers I know who handle that type of thing all the time.

This has a few benefits. First, I keep my focus on my wheelhouse, which is non-compete and trade secret litigation. Second, the client gets in touch with someone who knows the practice area better than I do. Third, people I refer those cases to are likely to return the favor.

So, sometimes it’s best to say “no” to taking on a potential client matter, even if it might be financially beneficial.

That brings me to Lesson 4. What’s the most important skill for a solo lawyer to master?

What is the most important skill for a solo lawyer?

I put this question out to Twitter and to the audience I spoke to at the State Bar annual meeting, and both times I got a lot of good answers. Here are some of those:

These are all good answers, but I say the most important skill for a solo lawyer—and maybe any lawyer (?)—is the ability to say no.

Specifically, to say no to committing to things that will take up your time.

It’s tempting, especially as a solo lawyer trying to develop business, to feel like you need to say yes to everything. Serve on that committee, make that presentation, go to that happy hour, attend that networking event. “Always be closing” etc.

But you have to keep in mind that your time is a precious commodity, especially as a solo.

Some might even say that time is your most precious commodity. But I disagree. I say your energy is your most precious commodity as a solo lawyer.

That’s Lesson 5.

What is the solo lawyer’s most precious commodity?

It took me a while to figure this out. For a while, I thought maybe I needed better time management skills to keep up with all the client work I was getting, not to mention the administrative tasks and business development.

But after a year of solo law practice, I’ve realized that even if I have enough time to do one more thing in my work day, that doesn’t necessarily mean I have the energy.

In other words, I have found that energy management is really the issue.

It reminds me of this Nintendo horse-racing game I used to play with my kids. You had to whip the horse to make it go faster, but if you whipped too much, the horse would get exhausted and fall behind.

It’s a simple concept, but one that I think lawyers really struggle with.

I think part of the problem is that lawyers and law firms tend to buy into this toxic notion that successful lawyers should have some unlimited store of energy.

Rise and grind! Stamina! Give 110% all the time! You hear a lot of this sort of thing, especially from lawyers who are selling something.

Don’t buy into that. Your energy is your most valuable commodity. You have to budget it, or you’re going to burn out, like one of those video game horses.

And if you don’t, who will?

________________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

Leave a Comment