This is an edited transcript of my interview with appellate lawyer Kendyl Hanks about lessons for lawyers (and others) from fly fishing. You can watch the video of the interview here.

Z: I’m Zach Wolfe. I’m here with Kendyl Hanks. Kendyl, welcome.

K: Thank you for having me.

Z: Thanks for joining us on the show. So, a lot of viewers probably already know Kendyl Hanks, the outstanding appellate practitioner in Texas, greenhouse gardener, dog lover, and all those good things. But you are also a fly-fisher.

K: I am. Yeah.

Z: We’re going to talk a little bit about fly fishing today and maybe how it applies to practicing law or maybe other things, but first, let me give you a chance to introduce yourself and talk a little bit about your law practice.

K: Sure. Thank you so much for having me. I’m a huge fan of your blog Five Minute Law. It’s always a good place to start, particularly like employment stuff, I’m always checking out your blog. I’m a shareholder with Greenberg Traurig in Austin. I have practiced in Texas and New York for the last about, I guess this year will be 20 years. I can’t believe it. Oh, I really can’t believe it. And I have had the good fortune to have an appellate practice, most times it’s in Texas, but I have cases throughout the country for some clients. We do a lot of test cases where we’re creating precedent, a lot of big cases, big verdicts, big judgments, things like that. And I was the daughter of a litigator and I love litigating, but I’m a huge fan of the appellate side. So one of my favorite things is to work with really talented trial lawyers, who I think live by the first principle of appellate law, which is the best strategy for winning an appeal is to win the trial. So, that’s a summary of my practice.

Z: I think that’s probably far too modest, and I know that because I experienced this firsthand. I remember one time I emailed you about this really interesting Texas Supreme Court case that came out, and then you emailed me back and you were like, yeah, that was my case.

K: Sorry.

Z: I should have known. But anyway, my favorite saying about trial versus appellate is “trial lawyers drive for show, and appellate lawyers putt for dough.”

K: [Laughing] I like that.

Z: But that’s golf. We’re going to talk about fly fishing now. But before I do that, you’re very popular on Twitter, and I thought, I’d go look at your Twitter profile.

K: Oh, gosh. Have I looked at that recently?

Z: It’s got three things. It’s got #AppellateTwitter, @LadyLawyerDiary, and #FlyFishing. So before we get to the fly fishing, what is #AppellateTwitter for people who don’t know?

K: I’m not a huge fan of social media, surprisingly. I’m not on Facebook. I actually found #AppellateTwitter because I was doing a program in Washington D.C. on recent developments in the U.S. Supreme court with some really wonderful panelists. A reporter from Bloomberg was live tweeting the program, and one of my colleagues said, they live tweeted your program. Now I gotta get on Twitter. So I got on Twitter and I think in the, in the description he had tagged #AppellateTwitter. I was like, oh my gosh, there’s this thing, appellate Twitter, this is amazing.

And, as I know you know, the Texas appellate community is very robust and close-knit community. We all sort of know each other and send each other business. And I saw a lot of those people on Twitter, which was sort of fun and a surprise. And we started talking about big cases, and trends in different courts, and fonts and spacing and footnotes and Oxford commas. I was like, I have found my people. So, appellate Twitter is just a wonderful community of people who sort of nerd out about law and support each other and send each other referrals. It’s a really great community, and I feel very lucky to have found it.

Z: Yeah, same here. And if anybody is not active on appellate Twitter, and you’re interested, go check it out for sure. Now how about this account called @LadyLawyerDiary?

K: Lady Lawyer Diary is an account that grew out of a hashtag, #LadyLawyerDiaries, which was basically a bunch of women who were connected through #AppellateTwitter. So it’s a lot of appellate lawyers, some professors, some in-house, a lot of law firm litigators, and we were talking about not so much appellate issues, although that’s kind of how we connected, it arose in the context of the #MeToo developments, Kozinski, and some of the other issues that were playing out a couple of years ago, and still playing out of course. The hashtag was taking off, and one of the things that we noticed, women in particular felt more comfortable talking about issues when they didn’t necessarily have to do so under their own name, for obvious reasons. There are a lot of fraught issues when it comes to sexual harassment, the pay gap, the lack of diversity, you know, traditionally, and it’s always been a challenge in the legal profession and in the courts.

So we, the group of us, not just me, a group of about a dozen or so of us started the handle as a forum. And we curate that forum, to start conversations, to facilitate discussions. We will post things for people who want to post anonymously. We do things behind the scenes that may not even reach social media, if it’s something particularly sensitive. And one of our co-founders testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee about reforms of the judiciary for reporting with respect to sexual harassment and things of that nature.

So we talk about diversity, inclusion, issues that affect women in the profession, and we try to do our best to promote women’s successes. Women, sometimes we can be really bad about tooting our own horn. And so we try to create a forum where we really encourage that. Like, if you’ve got a big success, a big promotion, and it’s something that’s not privileged, you can talk about it. We want to hear about it. And, and so we’d like to signal boost, things like that.

Z: Well . . . Kendyl, actually . . .

K: Actually . . . Tell me all about it, Zach, I want to hear all about it.

Z: No. Okay. All right. Let’s get to the fly fishing this past summer, you published an article in the ABA Litigation journal called Fly Fishing Lessons. And it’s a great article. Everybody should go read it in addition to watching our fabulous interview, but I’m curious, what kind of feedback have you gotten about the article?

K: It’s been interesting. I’ve gotten a lot of emails from people, some who I’ve known before, and some I’d never met before, who read it and who were either anglers and they were like, wow, I’ve never made this connection, and you’re so right. Or people who are not anglers, but they’re litigators or appellate lawyers and they’re like, wow, now I want to go fishing, which I think is fantastic.

So, great feedback. I mean, we’ve all written a lot of articles and spoken on legal developments and big cases, and this is very different. This is a very personal, almost a thought exercise in some ways about how something that I’m really passionate about in my personal life, I’ve learned has a lot of lessons for my professional life, and I didn’t even really necessarily make that connection until I got deeply into this article, and I was thought, that’s something I do in my career that is also something that is great in fly fishing, or something I don’t do professionally that I really should be doing more of.

Z: Yeah. Well, we’re going to dig into that, but let me start with the most basic question, and I’ll confess, I don’t really fish.

K: That’s ok.

Z: What is fly fishing?

K: So fly fishing, there’s different kinds of fishing, right? I mean, if you there’s commercial fishing with nets, right? There’s spin cast fishing, which is you toss out a heavy lure and then you reel it back in and then you toss it back out. And a lot of spin casting, you might use a fake lure, or you might use a worm, for example, you know, your traditional sitting by the pond with a worm on a hook.

Fly fishing is a different setup. It is a rod that uses the weight of the line to push an artificial fly out onto either the surface of the water or to a spot where you can pull it down through the water. And the idea is that it mimics the food source of the fish, usually the food source. Sometimes if it’s salmon fishing, for example, you might not want necessarily a food source. You might just want to make the fish angry and territorial, so something really flashy and obnoxious. But usually fly fishing is known for trying to mimic the food source of what a trout or something else you might be fishing for is going to go for.

And so there’s a little bit more strategy for it. You’re not actually throwing the worm in the water. You’re trying to recreate a creature on or in the water that is so enticing to the fish that they want to come up and catch it. So it’s not so much tossing something into the water as it is learning how to control the line in the air and how to get this itsy bitsy tiny little thing, you know, 30 feet out into moving water.

Z: Sounds challenging. I can sense the connection to appellate law, but tell me, what’s your earliest memory of fly fishing?

K: My mother’s family is from Idaho, and she grew up fly fishing. Maybe I was nine or ten. Certainly before 12 or 13. When I was about 13, we took a pack trip, like an 11-day pack trip with mules and everything in Yellowstone. So it was before that. Copper Basin is this beautiful basin in Idaho. They have gorgeous streams full of trout and otters and all sorts of wildlife. And I was young enough that I still had a spin rod, and we would put salmon eggs on the spin rod, which is like Ambrosia for trout. So, if you’ve got fish in a river and you want to catch a whole bunch of trout, and this is one of these trips. It was long enough that , we had trout for breakfast, trout with eggs, then we had trout for dinner. So we were literally eating what we were catching.

And so I just got a little bored and my dad was fly fishing. It looked really cool. And I mean, I was catching tons of fish, but this fly fishing thing was really intriguing to me. And so I tried it out. I was terrible at it. I was like 10 and hardly had the coordination. But I sort of got hooked on it after that.

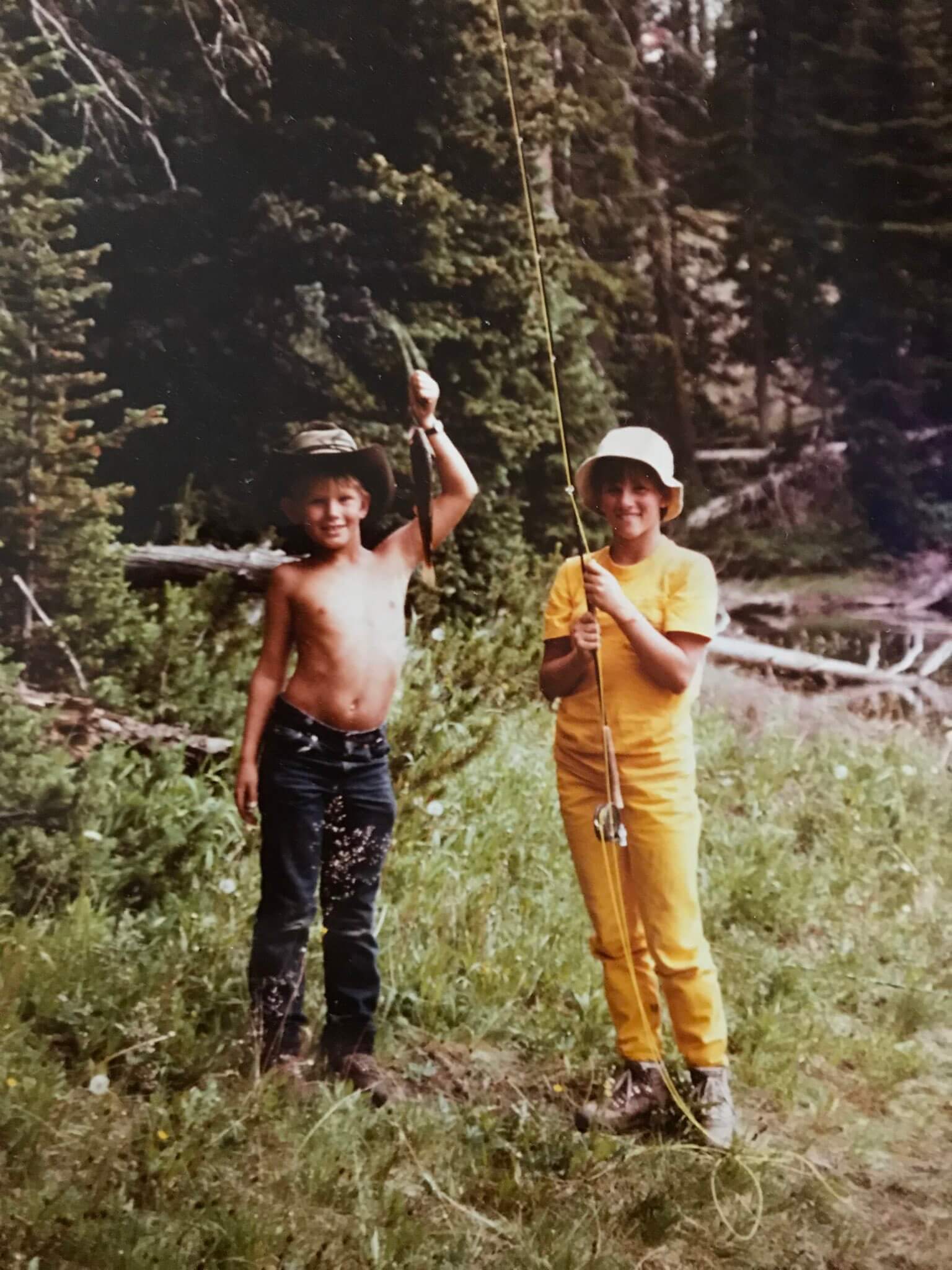

And then, by the time we took our Yellowstone trip, a year or two later—I think I posted this picture on Twitter once—I think my parents were worried about me getting lost in the forest. And so I was dressed in like head to toe bright yellow, right? I mean, I literally looked like a banana walking around Yellowstone park, but this is where I learned how to fly fish, up in Yellowstone, which now as an adult, I know is some of the most pristine and spectacular fly fishing in the world, which I couldn’t have appreciated as a child.

So those are my first memories, getting bored with regular fishing, with bait casting, with bait fishing and saying, you know, I really want to try that, even if I’m not good at it yet.

Z: I see. So you’ve been doing this a long time. Now in the article, you talked about issue spotting, which lawyers are familiar with. So tell us, how does issue spotting apply to fly fishing?

K: I think one of the challenges in appellate law is there may be 20 things that you think the trial court did wrong. This was clearly a bad decision. The question is what are the issues that are going to make the difference in the case? What are the points of error, the issues on appeal, you can narrow this down to that are going to get the court of appeals’ attention, persuade them that you are right, and reach the result that you want, which is to win. Whether, you know, to reverse, if you’re the appellant, or affirm, if you’re the appellee.

In fishing, I think it’s easy to want to just sort of throw anything out there. It’s like, they want salmon eggs, right? Fly fishing is maybe not for you. You really have to understand your audience. What are you fishing for? Are you fishing for brown trout fishing for rainbows? Brookies? Are you saltwater fishing? Are you fishing for striped bass, what is the water like? What are the aquatic insects like? What is the air like? I mean, you need to understand the environment in which fish are making their choices and you need to understand why fish make their choices, right? So trout care about three things—food, shelter, and sex—and depending on what they’re doing at a particular moment, they’re going to care about different things. And that drives your choices in terms of what flies you might pick.

Choosing a particular kind of fly: Is it a wet fly that goes under the surface? Is it a dry fly that sits on top? Is it a big, huge, obnoxious fly? Is it a teeny tiny—I’ve got some here that are like, you can barely see, that’ll catch enormous fish, even though they’re super tiny.

The process that goes into choosing the right kind of fly for a particular environment and a particular audience, a particular kind of fish on a particular day on a particular river is very much to me, feels like the same process that goes into picking the right issues for an appeal, especially in a high court. So, when you’ve got discretionary review at the Texas Supreme Court, they’re not necessarily going to care about a court of appeals or trial court having done something that should have been different. They’re going to care about the important stuff, the things that are going to set precedent that matters in the state. So for me, it’s not so much translatable in a template way, it’s translatable in a process way, if that makes sense.

Z: Oh, I absolutely see the connection. Just like you might have your favorite flies that you like to fish with, you’ve got your favorite issues, but those may not be the issues that your court of appeals cares about.

K: Exactly. I’ve had plenty of days on rivers where there are some flies that are my favorite flies. I love these flies. They’re pretty, they’re cool. They’re easy to tie on. I know how they go in the air. I know how to get them on the water. But if it’s not what the fish wants, it is going to be pointless. There have been different kinds of flies and kinds of fishing that I’ve had to learn in order to be successful on different kinds of rivers and in different kinds of environments, because the stuff I’m used to and I get excited about isn’t necessarily what the fish gets excited about.

Z: In the article you also talked about the importance of assembling your own fly-fishing outfit. So one, what is the outfit, and two, why is it important to assemble it yourself?

K: When we say outfit, usually what we’re talking about is the rod and the gear-up that we’re putting together. Although there’s plenty of great fly-fishing outfits in terms of, I have my stuff that I go out in, all of which has tons of pockets, which is something that is woefully lacking generally in women’s wear. A lot of people, the first time they learn, there’s a lot that goes into actually putting a rod and a reel and a line and a fly together before you can get on the river. And you’re not going to have those skills the first time you’re introduced to it. So someone is going to show you how to do that. But a lot of people, they may go fishing four or five times in their life, like on a trip with some folks or whatever, and somebody will just hand them a rod that’s already set up right. And say, okay, go out on the river, cast it around, see if you can catch some fish.

I think there is great value in putting that setup, that outfit together yourself. Getting the line on the rod, learning the knots and to tie the line—the line is the weighted part—and you take the line and you attach it to a leader, and then you take a leader and you attach it to tippit, and understanding what those pieces are.

It is very similar to when I was a younger associate, before everything was electronically filed, we’ll walk down to the Dallas courthouse, meet the clerk, see what it is that they do with the document, have a conversation with people. And putting different pieces of a brief together and understanding their role in a brief. An introduction is different from a summary of argument, is different from a statement of facts, is different from a statement of jurisdiction. They have different purposes. They have different consequences if you don’t get it right. So putting together sort of your outfit when you’re getting ready to go fishing helps educate you a lot on how it all works, how it all comes together.

This is so nerdy, by the way, like I’m listening to myself talk and I’m thinking, oh man, I’m going to get so much hell for this.

Z: Yeah, but it’s nerdy in a good way.

K: I hope so. It is very nerdy.

Z: You mentioned pockets, let’s see the vest.

K: Oh, okay. So this is my, I have a bunch of vests because I share them with people when I take them out, but this is my personal vest, that I’ve had for gosh, 20 years maybe. So, as you notice, tons and tons of pockets, pockets everywhere, it’s lined with pockets literally, and it actually has a creel on the back, so if I wanted to keep a fish—I don’t, I do catch and release all the time now—but you can actually stick a fish in the back of your vest.

Z: I could wear one of those to court, and like you’d stick highlighters and flags in it.

K: Right. Everything’s right here, got these little grabber things that, you know, it’s wonderful. I love it.

Z: And you want to show us your hat as well?

K: Oh, my hat. So this is one of the things that I was thinking when I wrote about diversity and inclusion in the article, and it’s something, obviously I care a lot about with @LadyLawyerDiaries. There’s not a lot of gear out there for women. So it’s sort of like when Sarah Weddington argued Roe vs. Wade at the U.S. Supreme Court, there were no women’s bathrooms. She had to go to a totally different floor to find a women’s bathroom. The fly-fishing industry is sort of the same, it’s really geared toward men. And so we’re constantly having to adapt to men’s gear, like men’s shoe sizes and vests and waders. And one of the things recently is that some shops are realizing there are a lot of women out there who like to fly fish. And one of my favorite fly shops is the Taos fly shop in New Mexico. And they did this hat, it’s “fish like a girl”

Z: I like it. Nice.

K: It is utilitarian as well, because it’s, you know, you’re out in the sun, you’re out in the water and you can easily get badly burned up in the mountains. But being a woman and fly fishing, particularly when I was growing up, when I was younger and took a year off from college to go fishing, basically, there just weren’t a lot of women who were out there all the time like I was. That’s starting to change, but not fast enough for me.

Z: Yeah, and in the article, you talked about “fishermansplaining.”

K: It’s like mansplaining. Right.

Z: That sounds pretty self-explanatory.

K: So there’s actually a story about that, that I did not put in the article, but when I was about 14, we were on a raft trip in the middle fork of the Salmon River. You stand up on the bow of the boat, moving through rapids and you’re casting from side to side to side to side. And there was a guy, it was a big group trip, probably about 20 people, or so, and there was this guy who came over and he’s like, wow, you really should be doing it this way and that way and this way.

And he takes my rod away and he starts casting and he grabbed himself right here in the lip, like with the hook. And I thought to myself, I just don’t need men to explain to me how to do it. I will do it the way I want to do it.

So “fishermansplaining” is just one of those things where everyone has their own way of doing it, their own way of learning. There are some truisms about the physics of how a line works, but a lot of it’s about personal style. And, I love learning and from accomplished anglers, but it’s like someone who comes in and edits, not the substance of your brief, but the style. They want to change all of your em-dashes to commas and semi-colons and stuff like that. That’s like, you know, don’t tell me how to cast to my fish. If I ask, you can tell me, but it’s the same in mansplaining, right? Like if I don’t ask for your advice, I actually don’t need it.

Z: Yeah, the catching the hook on the lip kind of makes me think of, it’s like a lawyer being in court and the judge says, what’s the standard of review, and you say “the usual one.”

K: Oh yes. The usual one. What? No, is it regular? Is it strict scrutiny? No, it’s the regular one, or something like that.

Z: The regular one, right. Now, another parallel between the fly fishing and practicing law is you said something about needing to master the basics before you get creative. What did you mean by that?

K: So, like I mentioned, the physics of a line, so this is unlike spin casting, where you have something that’s weighted at the end. So you’re literally tossing the weighted thing into the water. And that pulls the line out. Fly fishing, it’s this very long line. You have to manage that line in the air in order to propel a virtually weightless thing dozens of feet away.

There are certain basic skills that you need to learn about how that works, like riding a bike, right? You need to learn how the pedals work. You need to learn how forward motion goes, how to stop. Same thing in fly fishing, but once you get the basic rhythms down, then it’s a lot more nuanced about what works for your body style, for your height, for your arm length, all of that stuff.

And getting creative, there are a lot of different ways of casting and a lot of different ways of keeping the line in the air, of laying it down on the water, and people have sort of different ways they adapt to their own form. And that’s the creative part. So it’s like art, right, in many ways. You need to learn the basics of art before you can turn into a Picasso. I mean, not that I’m comparing myself to Picasso, but you know what I mean. Like you hear sometimes people say, oh, abstract art, like any 10-year-old could do that. Well, I mean, a lot of those masters they weren’t making abstract art as young artists. They were learning the fundamentals of art, and the medium, and the canvas, and all of that, before they started getting creative, if that makes sense.

Z: Yeah, and how would you apply that in an appellate practice?

K: You need to understand the court rules. You need to have a good, fundamental writing skill set. And I think a lot of us have voices as lawyers. I can read a brief and be like, I definitely wrote that brief. And I think a lot of people are like that. That was not necessarily the case when I was a younger lawyer, not just in things that were filed, obviously, which went through partners and things, but when I drafted them, I was so focused on just getting the argument, the law, the points, all of that out. I think as you grow as a lawyer, you sort of find your way of persuading that works with your voice, and that authenticity that’s specific to you in some ways, without making it about you. I think part of persuasion is finding a voice that is not just persuasive because it’s right, or it has a really good argument, but because it’s conveyed in a way that is persuasive to this particular audience, and compelling.

And fly fishing is like that. You can get the fundamentals down, like anybody can toss a line in the water and sometimes catch a fish, even if they have no idea what they’re doing, which is wonderful. I think beginner’s luck is a big thing in fly fishing, just like it is in litigation. But it’s not that one lucky hit, that fish that you managed to land, or that big case that you managed to win. It’s the consistency. It’s developing your practice and your voice and your skill sets so that you know your patterns, you know what battles to pick. Do those corollaries make sense?

Z: It makes a lot of sense. You could have the most creative legal argument in your case, but if you don’t understand the deadlines in the rules of civil procedure.

K: Yeah. I mean, if you just pop out into a local river and start taking fish home, you’re liable to get in a lot of trouble with the local fish and game. I mean, you need a license, there are limits to what kind of bait you can or can’t use, lures, there are regulations about barbless hooks. Flies that you buy have barbs on them, which make it harder for the fish to get off of them. And a lot of rivers that I fish require barbless. And if you don’t know any of that stuff, not only are you not operating correctly in the environment, you can actually get into trouble for it. So mastering the fundamentals is also about understanding the culture in which you’re working, and the rules that govern that culture, and being able to identify the most likely avenues for success.

Z: Can you cite unpublished cases in fly fishing?

K: Well, if fish tales count, then yes.

Z: Yes!

K: Although now nobody has an excuse anymore, because everybody’s got their phones and can take pictures. When I was growing up, 95% of the fish I caught, no one else ever saw them because I didn’t really walk around with a big camera. Maybe a guide took a picture, but everybody was like, I caught this 29-inch brook trout, which is not true, nobody is catching a 29-inch brook trout, you know what I mean? [I just fact-checked myself and indeed found an article pictures of the angler who caught a world-record 29-inch brook trout! So anything is possible.] Now we’ve got little phones. I can pull them out and take pictures. So yeah, everything gets published now, even if it’s technically unpublished.

Z: Right. It’s probably not as fun. Now in the article, you have a quote from Jeena Cho, and it says, “we know that when you’re in a stressed or fight or flight state, you are unable to access higher cognitive functions such as imagination.” What do you take away from that?

K: Well, first of all, Jeena is amazing. You know, she wrote the book Anxious Lawyer, and she writes a lot about mindfulness, mental health, and the legal profession. She’s just amazing, I love her. So I encourage anybody to look her up and read her stuff. What I take away from that is we, our chosen career is a very stressful one. Whether it’s family law, or criminal law, or business litigation with companies and employees and a lot of money on the line, it’s a lot of stress, a lot of pressure. Someone else is putting their future in some respect in our hands. And it’s a lot of stress. It’s not a coincidence that the legal profession has the highest incidents of substance abuse, depression, and suicide.

It takes a real toll. And I think that when you’re living in that constant stress place, it’s difficult to really sort of stretch your wings and get more creative about your practice. And so, Jeena’s talking about mindfulness, and how important mindfulness is to take us out of that fight or flight sort of mindset, to give ourselves the space to be thinking in a much bigger and creative way, instead of like, Oh my God, I must win, here are the reasons why: X, Y, and Z. Trying to pull ourselves out of that and saying, okay, let’s think about this case big picture. It’s not just about whether, you know, who wins this particular case. It’s about where the law has been, where it’s going, what it’s going to mean for different industries.

Employing that sort of mindfulness to the process makes us better lawyers. I think it makes us more persuasive. I think it allows us to communicate to the court why a particular case is important and why their decision is important and why they should agree with us, of course. But it also, I think, makes our practice more enjoyable and more sustainable long-term. Because if you’re practicing out of a constant sense of fear of failure—what if I don’t get promoted, or what if I don’t make partner, or what if I don’t make this kind of money, and what if I lose my job—if those are the decisions, those are the fears that are driving our decision making, that’s a really hard way to live. And I’ve lived that way plenty, don’t get me wrong. I’ve learned the hard way that that’s not a good way to live. And so I try to be much more deliberate and sort of, you know, coaxing that mindfulness state out of my process in a way that I wasn’t as good at when I was younger.

Z: What you just said is something that also comes across at the end of your fly-fishing article. And that was the thing that kind of caught me by surprise. You know, I could kind of guess some of the other parallels, but when you made that turn, that’s what really caught my attention. And especially this statement where you said “fly fishing teaches that embracing the process without judgment is plenty effective in achieving results.”

K: It’s so counterintuitive. We are so focused on quantifiable results and chalking up wins, and don’t get me wrong, those things are important. I have clients. Wins are important to them. You know, I’m a partner in a law firm. Those things are very important. But when those are the driving impulse, when we are so focused on results-oriented achievement, we lose the importance of the process that’s supposed to get us there. And I think that one of the things that fly fishing has really taught me is that if you invest in the process, the moments between the beginning and the end, and you engage in those moments in a meaningful way, you are inherently perpetuating positive results. hey may not necessarily be the ultimate perfect result that you want, but you’re perpetuating good positive results for yourself, for your client, for your firm, for the legal system. And I think that when people get tunnel vision focused on one specific thing that must be, and anything else is failure, you’re just setting yourself up for that. Because that’s not the way our system is set up, and that’s not the way fly fishing works.

Z: Yeah. That was my number one takeaway from the article.

K: Was it? That’s interesting.

Z: I mean, just the idea, it’s somewhat counterintuitive, but when you’re not worrying as much about the results, but just enjoying what you’re doing, you actually tend to get better results.

K: Yeah. Enjoying what you’re doing and also just being mindful of what you’re doing, even when you may not really love it. There’s certainly, you know, briefs that I’ve written where I was like, I really, this is not my favorite part of the brief, I really don’t want to work on it. But being mindful of that particular piece of the brief, why it matters, what it advances, how it fits into the bigger picture, that investment in the process and enjoying that process, I think really yields results that are good.

Z: Agreed. Now, before we finish up, I do want to mention Project Healing Waters. Tell us a little bit about that.

K: Of course. Project Healing Waters is a national nonprofit that operates throughout the country, that serves men and women in military service in our armed services and veterans who have suffered physical injury or invisible injuries. We work with a lot of service people and veterans who have PTSD or depression, very serious physical injuries, brain injuries, things of that nature. And one of the really amazing things about fly fishing—and this is supported by scientific studies—is that the process of fly fishing, the physical movements, tying flies like that very detailed, small work with your hands, focused attention, it’s amazing for rehabilitation. And so Project Healing Waters operates throughout the country. We have programs for our participants, teaching them how to tie flies, to build their own rods, to fish, and then we even take them out fly fishing places.

We have a place up in Montana called Freedom Ranch where we will bring veterans. They stay in the lodge and they fly fish right there on the water. I personally did not serve, but most of the men in my family have served in the U.S. military. It’s something that I love doing, and fly fishing has been a wonderful thing for my own mental health. When I was struggling with depression, fly fishing was something that really sort of pulled me out of that a bit. And I love being able to share that with people. And so it’s just a way of giving back and it’s a wonderful organization. I would love for people to check it out. We have great fundraisers. We have trips that we sell at these fundraisers and fly rods and all sorts of stuff. So, check it out.

Z: Great. So, we’re doing this interview in February 2021. We’ve all been on some form of quarantine for almost a year, most of us. So I’m guessing that has kind of put a damper on the fly fishing.

K: I have not been fly fishing in over a year, and it’s driving me crazy. I am trying to plan, I don’t have a scheduled vaccination yet, so I don’t know, but, I’m going to try and assume that that happens by the summer. And I’m definitely gonna get a couple of trips in, I’m going to try to do one in the Rockies somewhere, probably Southern Colorado or somewhere in New Mexico where I have family, and then probably something on the coast, either the coast of Texas has some really great flats fishing or, maybe in Florida, I have some pals out in Florida. Maybe we’ll go out to the keys and do some bone fishing or something like that.

Z: That sounds great. Now, when you eventually get to go on one of these trips, does your dog, Molly, get to come with you?

K: Yeah. Oh, do you want to see Molly? Come here.

Z: Oh yeah.

K: Oh, good girl. She’s tired. She was napping. Here’s Molly.

Z: Sleeping on the job.

K: No, she does not. She gets bored. And we’re sort of out in relatively remote places. There’s coyotes and eagles, and Molly is of the size that an eagle could pick her right up. And I’ve actually been with her out in New Mexico, like on a walk, and a coyote came right in between me and her. She was about 15 feet in front of me and had I not pitched an absolute fit . . . So yeah, she’s not much of a fishing dog. You kind of need to have a bigger dog to survive the perils of that kind of wilderness.

Z: Makes sense. Well, Kendyl, this has been great.

K: Are we done already? That went so fast.

Z: Well, is there anything you want to add?

K: It’s such a treat to talk to you. Obviously, it’s something that I’m really passionate about, and I love sharing it with people, and it’s a real treat to be invited. Thank you.

Z: You’re welcome. Yeah. I mean, like I said, I have no experience with fly fishing, but it’s really fun hearing you talk about it,

K: But we’re going to have to change that.

Z: Well, yeah, maybe I’ll learn. We’ll see. All right. Thanks, Kendyl. K: Thank you.

________

Kendyl T. Hanks is an appellate shareholder with the Austin office of Greenberg Traurig. She has earned some professional recognitions, but none has made her feel more alive than disappearing into the mountains, messing about in a river, and catching these fish (which were promptly released).

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). He has never caught a trout, but Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). He has never caught a trout, but Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

Leave a Comment