Prologue: Look Away

If you are interested in stories with happy endings, then you would be better off somewhere else. My name is Zach Wolfe, and it is my solemn duty to bring you the sordid tale of the Flaubert orphans, three children who inherited the old Real Cheap Windows factory when their parents died in a mysterious mansion fire.

As minors, the children had to rely on Mr. Edgar, the company’s lawyer, to guide them. “I have bad news for you,” Mr. Edgar said in his first meeting with the children. “Just before your parents perished, Real Cheap Windows hired Dawn Davis, the star salesperson for our most ruthless competitor, Paula Payne Windows.”

“Did Dawn have a non-compete?” young Rose Flaubert asked. “Oh, it’s worse than that,” Mr. Edgar replied as he coughed into his handkerchief. “Much, much worse.”

“You see, before leaving Paula Payne Windows, Dawn downloaded 7,500 confidential company documents to a portable hard drive,” Mr. Edgar said. “Paula Payne has now sued us,” he explained, “claiming those files contained its most closely guarded trade secrets.”

“A trade secret,” he continued, “is information that derives independent economic value from not being known or . . .”

“We know what a trade secret is,” Karl Flaubert interrupted. “But I’ve spent hours reading an award-winning legal blog by a very handsome young lawyer,” Karl said, “and it says that companies often claim that things like ordinary lists of customers are trade secrets, even when that information is readily ascertainable.”

Karl continued. “If we think the trade secrets claim is contrived, can’t we just make Paula Payne Windows specifically identify what the alleged trade secrets are?” he asked. “Otherwise, we’re just flying blind.”

Here, “flying blind” is an expression that means engaging in some action with little or no knowledge of the facts of the situation, such that you are likely to crash or collide with a metaphorical obstacle because you lack knowledge of certain crucial information.

Karl was right. If you had to defend a trade secrets claim without knowing specifically what the alleged trade secrets are, you would be flying blind. But I am sorry to say the rest of this story is rife with misfortune and despair. You should probably stop reading now.

Chapter One: The Pleadings

That night, Rose and Karl read the pleadings. Paula Payne Windows had filed a Complaint in federal court claiming that Dawn Davis violated the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act by transferring the files to the portable hard drive.

But the Complaint was quite vague about what the alleged trade secrets were: “confidential company information, including without limitation customer lists, vendor information, prices, information about business plans, and methods of doing business.”

Here, “vague” is a word used to refer to allegations that are “fuzzy,” or not sufficiently definite. Vague should not be confused with “ambiguous,” which means a statement that can be reasonably interpreted to have two or more distinctly different meanings.

Karl also reviewed the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which provide that a defendant can file a “Motion for More Definite Statement” when the plaintiff’s pleading is “so vague or ambiguous that the party cannot reasonably prepare a response.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(e). “That’s it,” Rose said, “we’ll tell Mr. Edgar to file a motion for more definite statement.”

But Mr. Edgar laughed when the children came to him with the idea. “Flauberts, nobody really files a motion for more definite statement,” he said. “Now, children, if we were in state court we could file ‘special exceptions,’ which are kind of the same thing, and still popular with some older lawyers.”

“But even then,” Mr. Edgar said after another fit of coughing, “the judge would probably just say ‘serve some interrogatories instead—that’s what discovery is for.'”

Sweety Flaubert, the youngest of the children, responded with baby talk that was incomprehensible to Mr. Edgar. But her siblings understood: “Shouldn’t a litigant be required to state sufficiently specific allegations to give the opposing party fair notice, before the powerful engine of discovery is invoked?”

Interrogatories are written questions that can be served in the discovery process in civil litigation. The party receiving the interrogatories must serve signed answers within 30 days, but the responding party also has the right to make objections. I can assure you that the Flaubert children were about to discover just how frustrating the responding party’s interrogatory answers can be.

Chapter Two: Interrogatories

At the urging of the Flaubert children, Mr. Edgar sent an interrogatory to the lawyer for Paula Payne Windows, asking him to “identify each alleged trade secret with reasonable particularity.” After 30 days, Paula Payne Windows responded by objecting and saying: “Subject to the objections, see the 7,500 files Dawn Davis downloaded to a portable hard drive on or about September 1, 2017.”

“Those documents are 170,000 pages long,” Rose fumed. Tying her hair back, she banged out a “Motion to Compel” on an old typewriter she found. She then presented the Motion to Compel to Mr. Edgar.

“Flauberts, I’m sorry,” Mr. Edgar said, “but we can’t just haul off and file a Motion to Compel.” He explained that under Rule 26 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, first he would have to “confer” with opposing counsel about the Motion. “So confer,” Karl said. “But it’s not that simple,” Mr. Edgar responded, “and I don’t like confrontation.”

Mr. Edgar went on to explain that there were also Local Rules and “Standing Orders” designed to discourage motions to compel. “The judge’s standing order says the lead lawyers must confer in person, [cough] so first we have to confer about the location of the conference.”

I know what you’re thinking. “Confer about where to confer? What a sorry state of affairs.” But I can assure you I have seen this very thing happen. Literally.

Sixty days later, Mr. Edgar filed the Motion to Compel, which the judge denied at a hearing five months later. “There must be something we can do to make them tell us what the trade secrets are,” Rose protested. “I mean, they’re the ones trying to get our fortune by claiming our company stole trade secrets.”

Chapter Three: Mandamus

“Well, there is one thing,” Mr. Edgar said, his voice trailing off. “But it will never work,” he said. “We could try filing a petition for writ of mandamus in the Court of Appeals.”

“Mandamus” is a Latin word that means “throw a Hail Mary.” The term “Hail Mary” refers to a prayer traditionally recited in the Roman Catholic church, or a football play where the quarterback throws the ball as hard as he can into the end zone in a last-second effort to win the game. The phrase now figuratively refers to any last-ditch strategy for victory that has a low chance of success.

“We understand the risk,” Karl said, “but we’re willing to try it.” Karl spent that night in the library researching case law on identification of trade secrets. “Rose, I think I’ve found something!” “It’s a Petition for Mandamus to the Texas Supreme Court in a similar case called In re Terra Energy Partners, LLC.”

The Terra Energy petition was a goldmine of helpful case law. Here, “goldmine” is used figuratively. A literal goldmine is an underground cavern where underpaid workers dig up a precious metal used in wedding bands. A figurative goldmine is a source of abundant helpful information.

“It turns out that many federal district courts across the nation have required plaintiffs to disclose the alleged trade secrets with specificity before discovery starts,” Karl told Rose. He rattled off several examples cited in the Terra Energy Petition:

- United Serv. Auto. Ass’n v. Mitek Sys., Inc., 289 F.R.D. 244, 248 (W.D. Tex. 2013)

- StoneEagle Servs., Inc. v. Valentine, No. 12-1687, 2013 WL 9554563, at *5 (N.D. Tex. June 5, 2013)

- Big Vision Private, Ltd. v. E.I. duPont de Nemours & Co., 1 F. Supp. 3d 224, 258-59 (S.D.N.Y. 2014)

- Zenimax Media, Inc. v. Oculus Vr, Inc., No. 3:14-CV-1849-P (BF), 2015 WL 11120582, at *3 (N.D. Tex. Feb. 13, 2015)

“If we can just cite these cases, the judge will have to order Paula Payne Windows to identify the trade secrets,” Karl said.

If this were an ordinary children’s story with a happy ending, I would report to you that Karl provided these cases to Mr. Edgar, who triumphantly cited them to the judge and obtained an order requiring specific identification of the trade secrets. But this story has no happy ending. You may want to avert your eyes as the rest of the tale unfolds.

The Flaubert children soon learned that the Petition for Writ of Mandamus in the Terra Energy case was denied, not once, but twice. First by the Houston Court of Appeals, second by the Texas Supreme Court.

“You see, Flauberts,” Mr. Edgar explained, “the very reasoning of the cases you found shows why mandamus won’t work.” “These cases reason that the trial court judge has broad discretion to order the plaintiff to identify the alleged trade secrets,” he said. “But obtaining a writ of mandamus requires showing the judge abused her discretion. It’s not enough to say the judge made the wrong decision.”

Chapter Four: The Corporate Rep Deposition

Now Rose was really angry. “Can’t we turn this around on Paula Payne Windows?” she asked. “If they’re going to claim that there are 170,000 pages of trade secrets, haven’t they opened the door to extensive discovery on all of those pages?” “You’re right,” Karl said. “And while I was researching mandamus, I saw something about Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 30(b)(6).”

“Yes, we call that a ‘corporate rep’ deposition,” Mr. Edgar said. He reluctantly agreed to serve a Rule 30(b)(6) notice of deposition requiring a representative of Paula Payne Windows to testify regarding all 170,000 pages of documents containing the alleged trade secrets.

A “corporate rep” deposition is a common discovery procedure used when one of the parties is a business such as a corporation or LLC. The party taking the deposition identifies the topics, and the responding company must prepare a representative to testify. The procedure is designed to prevent a company from hiding the ball about relevant information and who knows it. Here, “hiding the ball” is an expression that means . . . well, you get the idea.

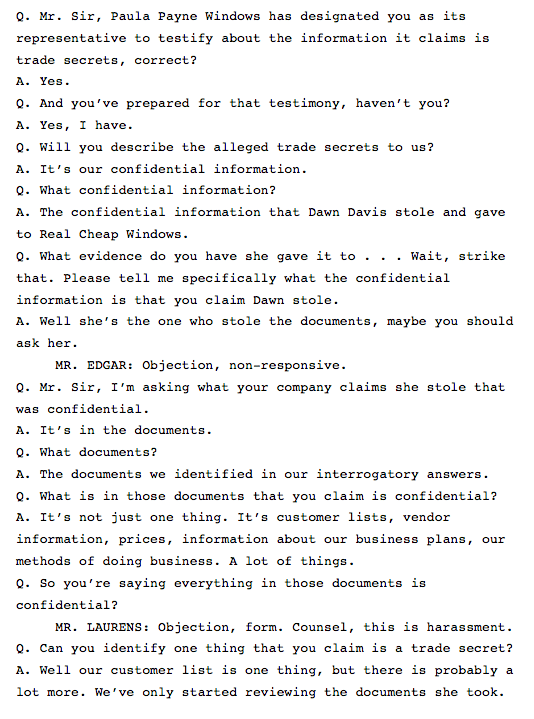

Paula Payne Windows designated Mr. Sir as its representative. Through my investigation I have obtained this portion of the deposition transcript:

“A lot of good that deposition did us for $37,000 in legal fees,” Rose said later. “I guess we’ll never find out what the trade secrets are. We’re doomed to be surprised at trial.”

Chapter Five: Motion for Summary Judgment

Sweety Flaubert then gurgled something Mr. Edgar could not understand, but Rose and Karl could: “Just force the issue by filing a motion for summary judgment on the ground that there is no evidence that the information is a trade secret.”

A motion for summary judgment asks the judge to rule on an issue as a matter of law. In this context, it would say that the trade secrets claim should be dismissed because there is no evidence that the information is actually a trade secret, and therefore no factual dispute for the jury to decide. In Texas state court procedure, they call it a “no evidence” motion.

The Flaubert children asked Mr. Edgar about filing a motion for summary judgment to force the issue. “In theory, that could work,” he said. “Sometimes a no evidence motion for summary judgment is useful to force the opposing party to put his cards on the table.”

“Put his cards on the table” is an expression that . . . Ok, I know. You’re getting sick of this.

“The problem with that kind of motion,” Mr. Edgar continued, “is that you’re not supposed to file it until the plaintiff has had an adequate time for discovery.” “If we file it now, Paula Payne Windows will just say it needs more time for discovery.”

The Flauberts were crestfallen. “Litigation really is a conundrum of esoterica,” Karl said.

_____________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at his firm Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters has named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation every year since 2020.

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at his firm Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters has named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation every year since 2020.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

Leave a Comment