On February 5, 2018, the day after the real Super Bowl, the Super Bowl of trade secrets trials started in federal court in San Francisco. You might have heard of some of the parties. The defendant was Uber. You may not have heard of the plaintiff, Waymo, but you probably know Waymo’s owner, a little company called Google.

The issue in a nutshell: did Google engineer Anthony Levandowski steal Google’s confidential self-driving car technology—they call it “LiDAR”—and take it to Uber?

This is the type of “departing employee” case I like to handle (on a slightly smaller scale), so it would have been fun to take the week off just to follow the trial, but alas, I had work to do for my own clients.

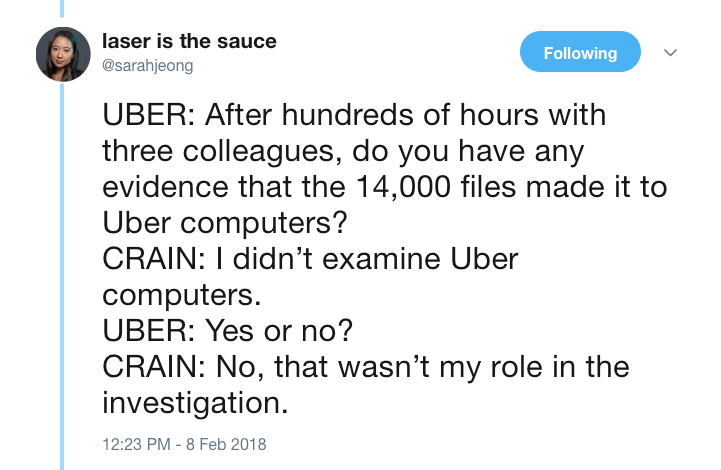

Fortunately, I was able to get the flavor of the trial by periodically checking my Twitter feed. Sarah Jeong, Senior Writer at The Verge, live-tweeted the trial and, after the case suddenly settled in the middle of trial, wrote this helpful wrap-up Who blinked first in Waymo v. Uber?

I bet the trial transcript—or even the tweet-stream—is a goldmine of lessons for lawyers who handle departing employee cases, and trial lawyers in general. But for now I’ll just share a little nugget about how to prepare witnesses to answer argumentative questions.

Laser is the Sauce

But first, in case you don’t know the back story, Fortune has a good timeline here. I’ll give you the simplified version:

- The amount of money to be made from self-driving car technology is roughly equivalent to the GDP of France

- Google spun out Waymo to develop this technology

- Levandowski left Google/Waymo to start “Otto” (which apparently rhymes with “Auto” – get it?)

- Uber CEO Travis Kalanick decided it would be cool to back his bro Levandowski and acquire Otto

- Waymo sued Otto and Uber for patent infringement and misappropriation of trade secrets

The case was unusual for several reasons: the net worth and public stature of the household-name parties, the high profile of the executives involved, the amount of alleged damages (close to $2 billion), the importance of the technology involved, and the Silicon Valley culture from which all of this emerged, to name a few.

But at its root, Waymo v. Uber was a fairly typical departing employee case: key employee does suspicious things, leaves first company, and goes to second company. First company sues second company for trade secrets misappropriation.

I haven’t studied the allegations in detail, but the picture that emerges from press coverage is bad “liability facts” for Uber—like some bad text messages and Levandowski downloading 14,000 proprietary Google documents shortly before leaving—but a weak damages case for Waymo. Apparently Waymo’s problem was that it couldn’t prove Uber actually received or did anything with the stolen files.

This is common. There are many trade secrets cases where the key employee is caught doing sneaky underhanded things he shouldn’t have done, but where it’s not clear whether those bad things actually caused damage to the employer.

My Witness Preparation Jam Sesh

That leads to my little lesson on witness preparation. Uber’s key trial theme was that it never received and used the alleged trade secrets. Specifically, Uber argued that the 14,000 files never got transferred to Uber. So, when Uber’s lawyer had Waymo’s expert witness on the stand, he zeroed in on that gap in Waymo’s evidence:

This is a good example of using cross-examination to make your argument. Uber’s lawyer is effectively standing before the jury and saying “ladies and gentlemen, there is no evidence the 14,000 files taken by Mr. Levandowski were ever transferred to Uber.” He’s just doing it in the form of a question to Waymo’s witness.

You can bet that Uber’s lawyer already knew the answer was no (probably from taking the witness’s deposition). So it was a good way to emphasize Uber’s key theme.

But of course, the question was a little misleading. This witness never examined Uber’s computers (assuming he was being truthful). That wasn’t his role. The fact that this witness didn’t find any evidence that the files got to Uber’s computers didn’t really mean a lot.

Still, I like the question. Part of the point of cross examination is to emphasize the points the witness has to concede that help your client’s case.

I also like the answer (at least on paper—it’s harder to say how it came off in person). Crain admitted the answer was no but got his little counter-jabs in at the same time. And that’s usually a good way to answer this kind of question, if you don’t take it too far.

Three Ways to Answer Argumentative Questions

There are basically three ways to answer this kind of argumentative question:

(1) The Just Answer the Question approach

(2) The Dog With a Bone approach

(3) The You Get to Argue Once approach

The first two approaches have some merit, but overall I like the third. Let’s break these down.

Just Answer the Question

The Just Answer the Question approach is just like it sounds. Let’s say the question is “did you take your employer’s customer list when you left?” If the answer is yes, then the witness just answers, “Yes.”

There are two main advantages to this approach. First, it is simple and easy to remember. As I explained in my post What the Ken Starr Interview Can Teach Lawyers About Witness Preparation—and Golf, a lot of witness preparation advice, even from professionals, is too complicated. It’s like telling a golfer to think about a dozen different things when swinging the club. Most witnesses are just not skilled enough to follow so many tips, especially under stress. So, there is some advantage to the simplicity of Just Answer the Question.

The second advantage of just answering the question is that the witness avoids looking evasive, arrogant, or overly defensive. That’s obvious. To avoid this risk, lawyers will sometimes coach the witness just to answer the question and not to throw in their counter-argument. “Save that point,” the lawyer will tell the witness, “and I’ll bring it up on re-direct.”

But there is a disadvantage to this approach. It makes it too easy for the questioning lawyer to get on a roll. Remember, what the cross-examining lawyer is really doing is making her argument in the form of questions to an adverse witness. If all the witness does is play along, he’s making it too easy. Maybe the witness will get a chance to bring up the point on re-direct, but the moment has passed. The damage has been done.

So there is something to be said for taking a more argumentative approach. When asked “did you take the customer list,” you can say “yes, but I never used it or gave it my new employer.”

Just don’t take this too far.

Dog With a Bone

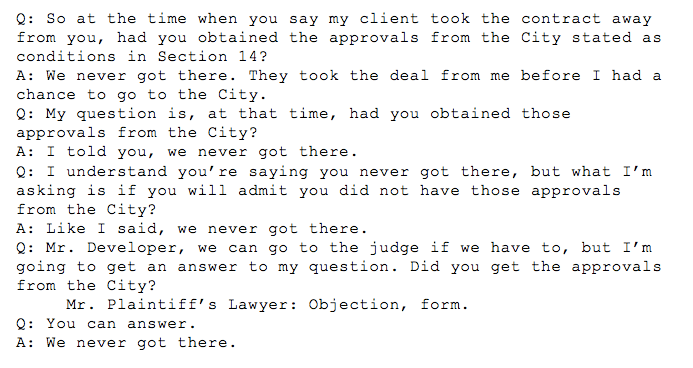

For example, I worked on a case involving a real estate deal gone bad. Our client was seeking millions in lost profits damages resulting from another real estate developer effectively “stealing” the deal. The defense lawyer’s key theme was that his client couldn’t steal any deal because the deal hadn’t been finalized.

That led to the defense lawyer asking the plaintiff a series of questions that looked kind of like this:

You can see the problem here. While the witness does a good job of making his point, he takes it too far. This makes him look stubborn and defensive. The jury may start thinking, “this guy seems really difficult, maybe he never would have gotten approval from the City.”

That leads me to the You Get to Argue Once approach.

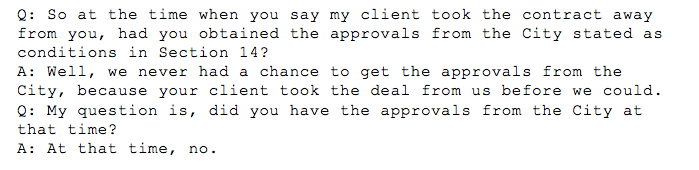

You Get to Argue Once

This is a middle ground. When the opposing lawyer asks an argumentative question that could give the jury a misleading impression, the witness makes the point he wants to make—but only once. If pressed after that, he just answers the question.

In the real estate case, it would go something like this in the courtroom:

Point made, but not overdone. And this is pretty similar to what Waymo’s witness did when asked if he found any evidence the 14,000 files were transferred to Uber’s computers.

Different Strokes for Different Folks

In general, I think the You Get to Argue Once approach is superior to the Just Answer the Question approach, and it is certainly better than the overly stubborn approach.

But of course, like everything in the law, it depends.

It depends in part on the personality of the witness. You tend to get two types: Nervous Ned and Alpha Dog.

Everybody gets a little nervous about testifying under oath, but Nervous Ned gets really nervous. This type just wants it all to be over as soon as possible. If just answering the question will end the ordeal faster, then this type is fine with just answering the question.

Alpha Dog is almost the opposite. This kind of witness relishes going toe-to-toe with the opposing lawyer. The witness can’t wait to unleash the counter-arguments when asked the tough questions. You know the type. Often this kind of witness is a CEO, executive, or self-made entrepreneur. And—let’s just be real about it—this type tends to be a certain gender.

If you’re the lawyer, you’ve got to coach Nervous Ned to stick up for himself a little more, and coach Alpha Dog to dial it down a notch or two. For the first type, the You Get to Argue Once approach means arguing a little more (unless that’s just too difficult, and then you may have to stick with baby steps and Just Answer the Question). For the second type, it means arguing less. In either case, you have to adjust for the personality.

And in both cases, the cardinal rules remain the same: listen carefully to the question, and always tell the truth.

Even if that means admitting you took the 14,000 files.

_______________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at his firm Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at his firm Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

Leave a Comment