Texas Ethics Opinion 665 says lawyers have an ethical duty to avoid inadvertently disclosing confidential metadata, but not an ethical duty to disclose they received inadvertently-sent metadata

Does a lawyer have an ethical duty to avoid sending opposing counsel a document containing metadata that reveals confidential client information? Does the receiving lawyer have a duty to inform the sending lawyer of the receipt of confidential metadata and to refrain from using the information obtained therefrom?

Did I really just use the word “therefrom” in Five Minute Law? Please don’t report me to Bryan Garner.

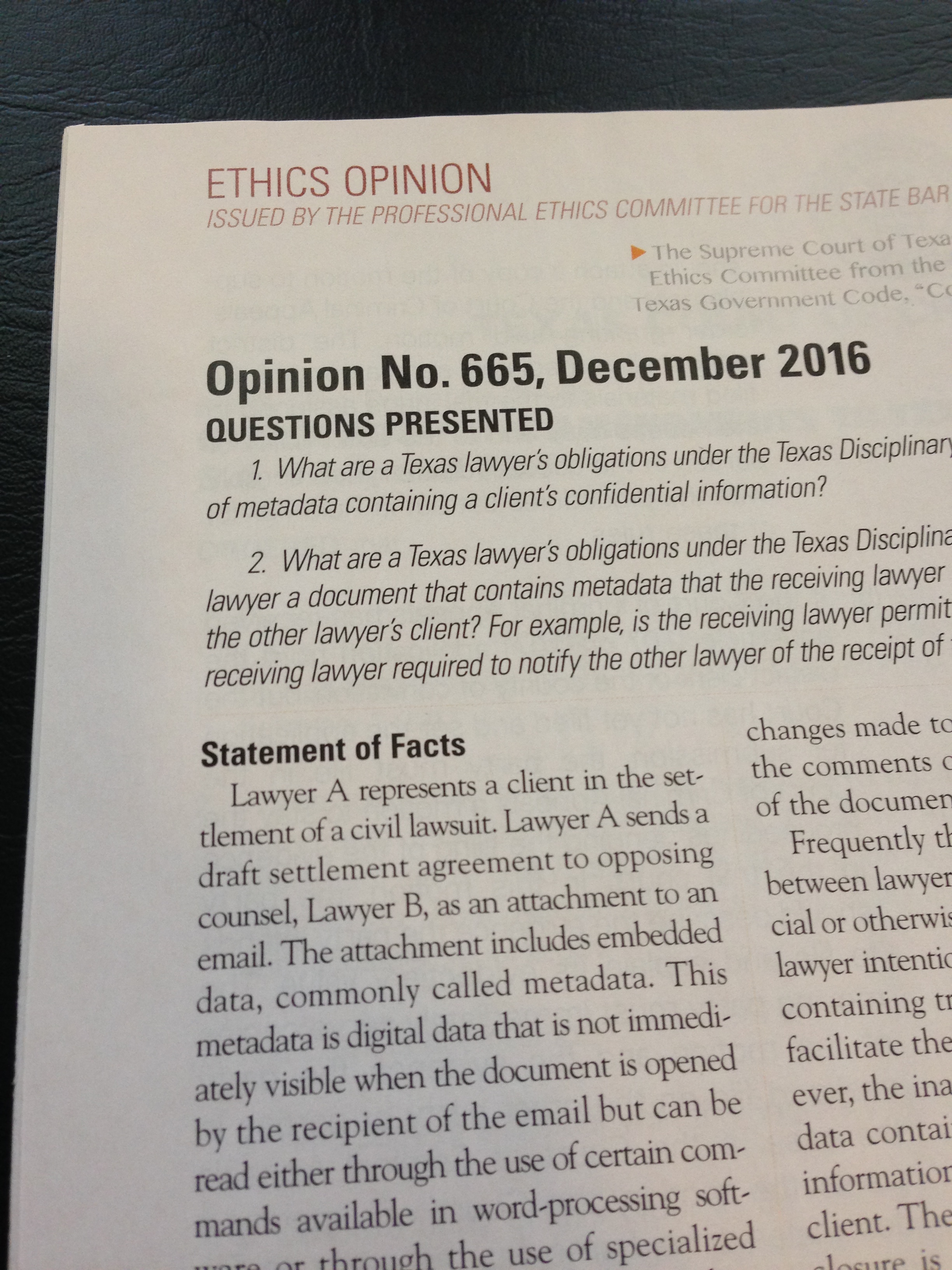

In any case, the Professional Ethics Committee for the State Bar of Texas recently addressed these questions in Opinion No. 665, which appeared in the January 2017 Texas Bar Journal. The Committee said yes, a Texas lawyer generally has an ethical duty to avoid transmission of confidential metadata, and no, a Texas lawyer generally does not have an ethical duty to notify opposing counsel of the inadvertent receipt of confidential metadata.

In short, you could say the Texas rule on inadvertent disclosure of metadata is don’t disclose. If you’re the sending lawyer, don’t disclose confidential metadata. If you’re the receiving lawyer, you don’t have to disclose that you received it.

The Committee included this important qualification: the opinion applies only to the “voluntary transmission of electronic documents outside the normal course of discovery.” Disclosure of metadata in discovery—an issue currently before the Texas Supreme Court in the State Farm case—is an entirely different subject.

The second part of Opinion 665 is consistent with Opinion 664, which I covered here. Opinion 664 said generally Texas lawyers do not have an ethical duty to notify opposing counsel they have inadvertently received confidential information. You might even say Opinion 665 simply applies Opinion 664 to metadata.

Once again, this puts Texas at odds with the ABA’s Model Rule of Professional Conduct 4.4(b), which requires a lawyer to promptly notify the sender of the receipt of inadvertently-sent electronically stored information. This is Texas, the home of rugged individualism. If the other guy inadvertently sends you confidential information, that’s his problem.

But there is a limit. Would you believe the Texas ethics rules require lawyers to be honest? It’s right there in Rule 8.04(a)(3), which says a lawyer shall not “engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation,” and Rule 3.03(a)(1), which requires that a lawyer shall not knowingly “make a false statement of material fact or law to a tribunal.” You can use confidential metadata opposing counsel inadvertently sent you; you just can’t lie about it.

In the Committee’s words:

[A]lthough the Texas Disciplinary Rules do not prohibit a lawyer from searching for, extracting, or using metadata and do not require a lawyer to notify any person concerning metadata obtained from a document received, a lawyer who has reviewed metadata must not, through action or inaction, convey to any person or adjudicative body information that is misleading or false because the information conveyed does not take into account what the lawyer has learned from such metadata.

That sounds reasonable. But it’s so abstract. What does it really mean?

Application of the Texas “don’t disclose” rule to metadata in a settlement agreement

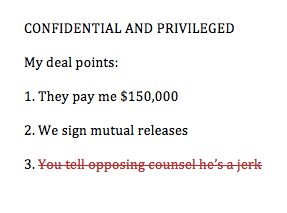

Let’s make this concrete with my favorite hypothetical non-compete lawsuit, Paula Payne Windows v. Dawn Davis. Suppose Dawn’s lawyer sends Dawn Paula Payne’s proposed settlement agreement in Microsoft Word. Dawn revises it and inserts some confidential comments, such as “change this to a one-year non-compete, but I’ll agree to two years if that’s what it takes—I just want this nightmare to be over!”

Dawn’s lawyer emails Paula Payne’s lawyer, Sam Sneaky, a Word document containing metadata that allows Sam to recover and review Dawn’s comments, including the comment about the length of the non-compete. Sam decides not to tell Dawn’s lawyer about the inadvertent disclosure. Knowing that Dawn is desperate to settle and will cave on the non-compete, Sam sends back a demand for more money and a two-year non-compete.

So has anyone broken any ethical rules under Opinion No. 665?

Dawn’s lawyer probably failed to meet his duties of competent representation (see Rule 1.01) and maintaining confidentiality of client information (Rule 1.05). According to Opinion 665:

Lawyers . . . have a duty to take reasonable measures to avoid the transmission of confidential information embedded in electronic documents, including the employment of reasonably available technical means to remove such metadata before sending such documents to persons to whom such confidential information is not to be revealed pursuant to the provisions of Rule 1.05.

Let’s assume Dawn’s lawyer knew the original Word document had sensitive client communications in it and should have known those communications could be recovered from the metadata in the new document. In that case, Dawn’s lawyer should have taken reasonable measures such as using a common metadata-scrubbing program when emailing the document to opposing counsel.

On the other hand, Dawn’s lawyer only has to take reasonable measures. “Not every inadvertent disclosure of confidential information in metadata will violate Rule 1.05.”

What about Sam Sneaky? Under the ABA Rule, you could argue Sam had a duty to promptly notify Dawn’s lawyer that the confidential metadata was inadvertently sent. But under Opinion 665, he’s fine in Texas.

That is, unless he conveys information that is false or misleading because it doesn’t take into account what he learned from the metadata. For example, after reviewing the confidential metadata, Sam couldn’t say to Dawn’s lawyer, “I have no idea what length of non-compete your client is willing to agree to, but my client insists on two years.” That would be dishonest. It’s a statement Sam could truthfully make before seeing the confidential metadata, but not after.

Admittedly, this hypothetical is pretty contrived. Who talks like that?

Let’s imagine something more subtle and realistic. Can Sam say to Dawn’s lawyer, “we have to insist on a two-year non-compete because anything less than that won’t adequately protect my client”? That statement is misleading, you could argue, because it omits the material fact that Sam is insisting on the two-year non-compete because he knows from the inadvertently-disclosed metadata that Dawn will agree to it.

The bottom line seems to be this: when Texas lawyers receive confidential metadata from opposing counsel, they don’t have to disclose they received it, and they can use it to their advantage. They just have to be careful what they say after receiving it.

Is this the Cowboy Way?

I’ll be honest. I don’t like this. Ethics Opinion 665, like Opinion 664 before it, seems to make Texas an outlier, and in the wrong direction. I prefer the approach of the ABA Model Rule.

Yes, Texas is the Lone Star State, where the legacy of Old West rugged individualism is strong. But we should also remember “Tejas” means “friendship.” And last I checked, Texas was still part of the Bible Belt. The Bible says “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” If you inadvertently sent a document containing confidential metadata and opposing counsel discovered it, wouldn’t you want him to tell you?

I’m not saying Ethics Opinion 665 is wrong. It’s a reasonable interpretation of the existing disciplinary rules. But using confidential information that opposing counsel inadvertently sends you just doesn’t feel like the Cowboy Way. If your neighbor’s cattle wander onto your ranch because he wasn’t careful, you don’t keep them and say “that’s his problem.”

Perhaps this comes down to the difference between “professionalism” and “ethics.” Ethics, in this context, means complying with a specific set of rules. Professionalism, on the other hand, is a higher—and admittedly fuzzier—standard. Telling a lawyer he accidentally sent you something you know he didn’t mean to send you is good professional courtesy, even if the Rules of Professional Conduct don’t require it.

It’s just following the Golden Rule. And the principles derived therefrom.

___________________

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

Comments:

Sadly, this situation shows that people (in this case, the TX State Bar Committee, can tie themselves in knots by differentiating between what they perceive as “legally ethical” as opposed to “personally ethical” acts. Wouldn’t it be a bit saner world if “A could equal B”, in talking about ethics?