Do Northern California federal courts have jurisdiction over every Gmail user who emails confidential information?

The answer is no, but give points for creativity to the plaintiff in OOO Brunswick Rail Management v. Sultanov, who at least made the argument. More about that later.

If you like trade secrets cases, you’ve got to love the Brunswick case. It has everything. A Russian company. A renegade employee emailing confidential company documents to his personal Gmail account (allegedly). And something every trade secret litigation nerd wanted to see: an application for an ex parte seizure order under the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act.

In May 2016, then-President Obama signed the Defend Trade Secrets Act (DTSA). As I reported here, the chief practical effect of the DTSA was to give plaintiffs in trade secrets cases the option of suing in federal or state court. Unless you’re a trade secrets litigator like me, that’s pretty boring.

But the sexy part of the DTSA was the new ex parte seizure remedy. “Ex parte” is a Latin phrase that means “you don’t have to tell the judge how crappy your case is.” But seriously, it means only one side presents its case to the judge. The DTSA allows a judge to order federal marshals to seize a person’s property—typically we’re talking about a computer or smartphone—without notice to that person.

This caused some serious handwringing in the legal community. We have an “adversary” system of justice that guarantees due process—at least for now—so lawyers worried about potential abuse of the ex parte seizure remedy.

I agreed with critics who saw no real need for a federal trade secrets statute, but I wasn’t too concerned about a wave of ex parte seizure orders. The DTSA has strict requirements for such orders, and I predicted most federal judges would not grant such an extreme remedy when an ordinary temporary restraining order would do.

A test case for the DTSA’s ex parte seizure remedy

Brunswick was one of the first cases to test my theory. The complaint presented a fairly ordinary misappropriation of trade secrets case, but with a Russian twist:

- Brunswick is a Russian company that leases railcars to large corporate clients in Russia. After beginning a process to restructure its debt, Brunswick sued its former CEO in a confidential arbitration.

- A Russian-American named Sultanov went to work for Brunswick and signed a typical confidentiality agreement. Essentially, Sultanov agreed not to disclose Brunswick’s confidential information, that all of Brunswick’s internal information is confidential, and that he would return all Brunswick confidential information on request.

- Sultanov started acting suspiciously: taking calls one floor up from his office, asking a lot of questions about the debt restructuring, and even coming to work on the weekends. (Big law firm associates take note.)

- Sultanov emailed confidential Brunswick documents from his work email to his personal Gmail account. He then deleted the emails from his Brunswick account and emptied his “trash” folder. The emailed information could be highly damaging to Brunswick’s debt restructuring negotiations with its creditors.

- Phone records showed Sultanov repeatedly calling a Brunswick creditor involved in the restructuring.

- When confronted, Sultanov admitted sending the emails but refused to return his company-issued mobile phone and laptop.

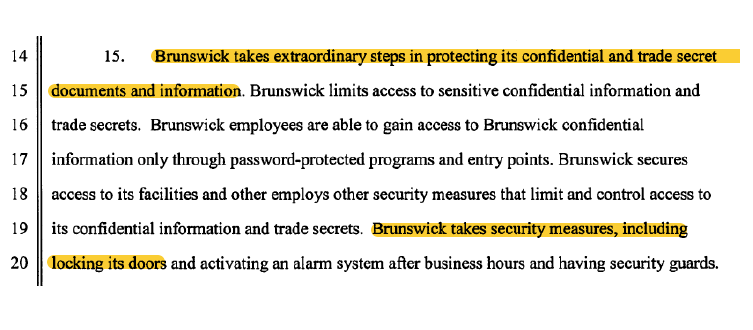

And my favorite allegation from the complaint:

“Extraordinary steps” including “locking its doors.” Wow. I knew Russia had nuclear weapons, but I didn’t realize it now has access to modern door-locking technology.[1]

So far, these facts present an interesting, but typical, trade secrets case against a former employee.[2] Emailing company files to your personal Gmail account on the sly? Come on, man! That’s so last decade. It’s more obvious than getting down on the floor and sticking a USB drive in your PC tower.

But if you’re Brunswick’s lawyer, where do you sue Sultanov? How can you get his computer and phone back quickly? And how can you do it without giving him a chance to tell his side of the story?

It’s time to get creative.

Trade secrets case tests two novel theories

First, a little background for my non-lawyer readers. To sue someone in federal court, you need both “subject matter” jurisdiction and “personal” jurisdiction. Subject matter jurisdiction means the court has jurisdiction to hear the type of claim you’re making. Personal jurisdiction means that the court has jurisdiction over the person you’re suing.

Personal jurisdiction is complicated, but in a trade secrets case, it boils down to this: you need to show that the person you’re suing took or received the alleged trade secrets in the state where you’re suing him (as I explained here).

Brunswick came up with the brilliant idea of suing Sultanov in federal court in California for violating the Defend Trade Secrets Act. Subject matter jurisdiction? Check.[3]

Personal jurisdiction? That was a little harder. Sultanov’s sneaky shenanigans all took place in Russia, right?

Not exactly. If you had Encyclopedia Brown on the case, he’d spot a detail you might have missed: Sultanov emailed Brunswick’s confidential information to his Gmail account. And where is his gmail account located? You guessed it: Google headquarters in Silicon Valley.

Brunswick argued in its brief that Sultanov was subject to personal jurisdiction in the Northern District of California because he emailed the trade secrets at issue to his Gmail account hosted by Google. Not only that, Sultanov went to high school and college in California and “certainly would be aware that Google is based in California and that his intentional use of Gmail would have effects in California.”

Like I said, points for creativity.

Judge denies ex parte seizure order and rejects creative jurisdiction argument

Brunswick filed suit on January 4, 2017 asking for an ex parte seizure order against Sultanov under the Defend Trade Secrets Act. Two days later, U.S. District Judge Edward J. Avila issued this opinion denying a seizure order but granting a temporary restraining order (TRO).

Judge Davila cited the DTSA provision that a court can grant an ex parte seizure order only if it finds that another form of equitable relief would be inadequate. “Here, the Court finds that seizure under the DTSA is unnecessary because the Court will order that Sultanov must deliver these devices to the Court at the time of the hearing scheduled below, and in the meantime, the devices may not be accessed or modified.”

This seems like the sensible ruling, and the one you would expect most federal judges to make in this situation. It’s the reason I expected that granting an ex parte seizure order would be very rare.

So what happened when Sultanov’s lawyer got a chance to respond? If you’re a litigator, or if you’ve watched a lot of episodes of Law and Order, you know what’s coming.

First, would you believe there was another side to the story? Sultanov’s response painted a very different picture than Brunswick’s complaint. Far from a dishonest employee stealing the company’s trade secrets for personal gain, Sultanov portrayed himself as a conscientious whistleblower exposing corporate fraud, even against his own interest.

I would share more details, but most of Sultanov’s publicly available response looked like this:

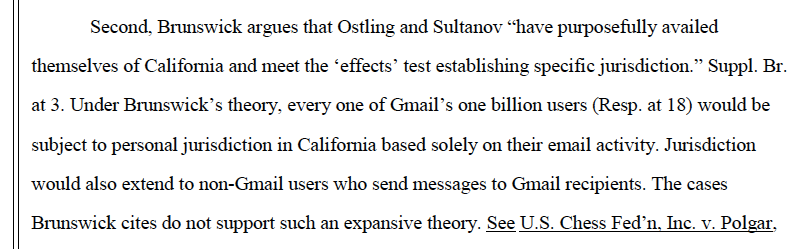

Second, Sultanov attacked Brunswick’s creative “Gmail” theory of personal jurisdiction. After hearing arguments from both sides on the personal jurisdiction issue, the judge issued this order siding with Sultanov and rejecting the Gmail theory:

As a lawyer who has read literally hundreds of personal jurisdiction cases, I can tell you the judge was on solid legal ground.[4] Plus, the Gmail argument would make the Northern District of California to trade secrets litigation what the Eastern District of Texas has been to patent litigation.

That would be bad. I’ve traveled to both Silicon Valley and the Eastern District of Texas for litigation matters. I had some great Korean food in Palo Alto, but California is just too expensive. Tyler and Marshall, on the other hand, are much cheaper and have better BBQ joints.

But I digress.

A lesson about the adversary system

The Brunswick case provides a great lesson about the adversary system, due process, and the reason people got so worked up about the ex parte seizure remedy in the Defend Trade Secrets Act.

First, even when the lawyer asking for an ex parte order is totally honest, he’s unlikely to volunteer any important reasons not to grant the relief. The judge is only going to get one side of the story.

A related problem is that when the judge only hears from one side, no one involved has a strong personal incentive to test the underlying assumptions of the lawsuit. For example, does the court even have personal jurisdiction over the defendant?

So, when the judge in Brunswick issued a 2000-word order granting a TRO against Sultanov, the word “jurisdiction” appeared exactly zero times.

I wasn’t there, but I’m guessing when Judge Davila issued the ex parte order two days after the suit was filed, there wasn’t a robust discussion about whether Sultanov was subject to personal jurisdiction. I’m wondering if the judge was a little ticked off when he later realized that the jurisdictional basis for the TRO he signed was the Gmail theory.

*Update: After allowing limited jurisdictional discovery, Judge Davila granted Sultanov’s motion to dismiss the case for lack of personal jurisdiction. The judge again rejected Brunswick’s Gmail jurisdiction theory. You can read that opinion here.

__________________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020 and 2021.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

[1] In fairness to Brunswick, the Complaint also alleged some pretty extensive additional efforts to protect confidential information.

[2] For simplicity, I’m leaving out facts about Brunswick’s claim against another employee, its former CEO Paul Ostling. Adding those facts would turn this into “Ten Minute Law.”

[3] Federal courts have original but not exclusive jurisdiction over DTSA claims. 18 U.S.C. § 1836(c).

[4] The judge also found that the evidence did not support Brunswick’s additional allegation that Sultanov maintained a personal residence in California. The judge cited Sultanov’s testimony that the address at issue was a family friend’s property that he sometimes used as a mailing address.

Leave a Comment