Why the scare quotes around employee “fiduciary” duty? I’ll get to that in a minute.

First, let’s talk about lost profits damages.

What should an appellate court do when there is some evidence of lost profits damages, but the amount found by the jury is not supported by the evidence? That is just one of the difficult questions raised by the revised opinion on lost profits damages in Rhymes v. Filter Resources, a typical Fiduciary Duty Lite case.

Fiduciary Duty Lite? As I wrote here, that is the flavor of fiduciary duty that an employee owes to an employer under Texas law. As I explained, it doesn’t really make sense to call it “fiduciary” duty, but that’s the label Texas courts have used so we’re probably stuck with it.

Essentially, Fiduciary Duty Lite says that an employee can prepare to compete with his employer while still employed but cannot actually start competing until after leaving the employer. If you suspect that maintaining this distinction is easier in theory than in practice, you may have a bright future in Fiduciary Duty Lite litigation.

But first you have to pass this quiz. Here are the facts of Rhymes in simplified form:

- Employee signs agreement with Company that says Employee will not solicit the Customers for one year after leaving Company.

- Employee speaks to attorney who provides formal legal opinion that non-solicitation clause is “not worth a s**t.”

- Employee gets access to Company’s double super-secret information, such as “products, prices, contracts, and financial, vendor, and customer information” (i.e. the same kind of information every sales employee gets).

- Employee, while employed by Company, prepares to compete with Company, including forming Competitor and communicating with Customers about Employee’s plans.

- But Employee testifies he did not actually “solicit” Customers before leaving Company (whatever that means).

- After leaving Company and joining Competitor, Employee quickly begins selling to his old Customers from Company.

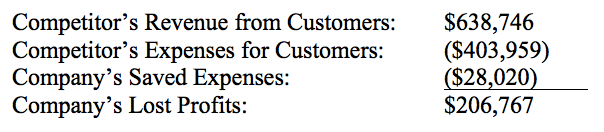

- Company sues Employee and Competitor. Law firm partner who represents Company buys new Lexus. At trial, Company’s damages expert presents these numbers for Year 1:

- Company’s expert also testifies that Company’s lost profits for a five-year period would be $622,800, using Year 1 as a base line and assuming a gradual decrease over Years 2-5 to account for risk and customer attrition.

- Employee and Competitor present no contrary expert testimony.

- Jury finds that Employee breached his Fiduciary Duty Lite and finds damages of $620,000 for Year 1 and zero dollars for Years 2-5.

Got it? Now, here is the multiple choice question.

QUESTION: Assuming there was sufficient evidence that Employee breached his Fiduciary Duty Lite, what is the right amount of damages to award to Company based on the jury verdict?

A. $620,000. This is the amount found by the jury, and there is some evidence to support it because Employee earned revenue of over $638,000 in Year 1.

B. $206,767. Lost profits damages must be based on net profits, not gross revenues, so there is insufficient evidence to award $620,000 for Year 1 but sufficient evidence to award $206,767 for Year 1.

C. $622,800. Company’s damages expert testified to this amount of net profits for Years 1-5 without contradiction.

D. Zero dollars. There is legally insufficient evidence to support the amount of damages found by the jury.

E. None of the above. A new trial should be ordered. (I added this choice strictly for my appellate ninjas.)

If you’re struggling, don’t feel bad. It took the Beaumont Court of Appeals two tries to come up with its final answer.

Here’s one important clarification: you are allowed to suggest a “remittitur,” which means giving the winning party the choice of a lower amount of damages or a new trial. With that clarification, the best answer–and the answer ultimately chosen by the Beaumont Court of Appeals in this revised opinion–is B. But you could make a plausible case for each of these answers.

A. $620,000. To support this answer you could cite the principle that the jury’s answer must be upheld as long as there is some evidence to support it. In fact, this was the answer the Beaumont Court of Appeals chose in its original opinion, reasoning that this amount was within the range of evidence presented at trial. But the problem with this answer is that the jury’s answer on damages was specifically broken down by time period, and there was no evidence that the Company would have made net profits of $620,000 during Year 1.

B. $206,767. There was evidence that this was the amount of net profits for Year 1. For this reason, this was the answer ultimately chosen by the Beaumont Court of Appeals (in a revised opinion), suggesting a remittitur of this amount.

C. $622,800. There was some evidence to support this amount–testimony from the Company’s damages expert–but the problem with this answer is that the jury is free to reject even un-contradicted expert testimony.

D. Zero dollars. It is true that there was legally insufficient evidence to support the amount of damages found by the jury. But when there is evidence of some amount of damages, the Court of Appeals typically will not reverse and render judgment for the defendant, but will reverse and remand for a new trial. Which leads to . . .

E. None of the above – order a new trial. The Court of Appeals could have chosen this answer, because there was insufficient evidence to support the amount of damages awarded by the jury. But this is why the remittitur procedure exists, to give the Court of Appeals the more efficient option of awarding a smaller amount of damages rather than subjecting the parties to the time and expense of a new trial.

Thank you for playing!

_________________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022. He made up the part about the Lexus.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

Leave a Comment