There is something almost surreal about a Houston courtroom packed with Houston lawyers watching some of Houston’s most prominent lawyers argue about whether a Houston law school’s new name infringes the trademarks of another Houston law school.

That was the scene on August 26, 2016 in U.S. District Judge Keith Ellison’s courtroom. Judge Ellison heard lengthy presentations by two teams of lawyers. The judge interjected questions and comments but made no ruling. You can read the motion for injunction here and the response here.

Spoiler Alert: Judge Ellison GRANTED the temporary injunction in this 42-page opinion. You can read my analysis of the opinion here.

For readers who are not Houston lawyers, a little background. South Texas College of Law is a private law school located in downtown Houston. It changed its name to Houston College of Law. The nearby University of Houston promptly sued Houston College of Law for trademark infringement, claiming that the new name was likely to be confused with the public University of Houston, which has its own law school.[1]

Shortly after being sued, Houston College of Law received a gift: this opinion from the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals holding that there was no likelihood of confusion between “Florida International University” and “Florida National University.”[2] Houston College of Law argued that this Florida case provided a “blueprint” for the Houston case. However, the University of Houston argued that the Florida case had significantly different facts.

Watching this hearing was more educational than attending any trademark litigation seminar. Among a host of intriguing issues raised, these stood out:

1. What is the Name of the Law School at the University of Houston?

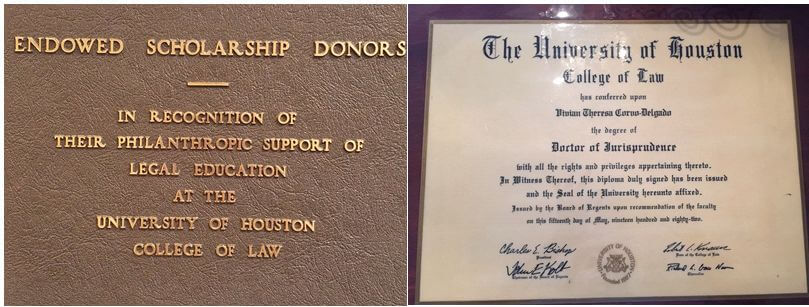

You would think this would be an easy issue. Over the years, the law school at the University of Houston has called itself the “University of Houston College of Law,” “Bates College of Law,” and the “University of Houston Law Center.”

The defendant argued that “University of Houston Law Center” has been the name since 1982, and that UH has abandoned “University of Houston College of Law.” The plaintiff argued that despite the change to the primary name “University of Houston Law Center,” UH has continued to use “College of Law” on diplomas and other materials.

Why does it matter? For one thing, the University of Houston did not include “University of Houston Law Center” on the list of registered and common law trademarks it sought to protect. It is easier to show a likelihood of confusion between “Houston College of Law” and “University of Houston College of Law” than to show a likelihood of confusion between “Houston College of Law” and “University of Houston Law Center.” A rose by any other name may smell as sweet, but in trademark litigation, the name’s the thing.

Judge Ellison did not resolve this issue at the hearing, but it was interesting that he asked more than once whether the defendant’s new name could cause some confusion with the name “University of Houston Law Center.” There was also a lot of argument about school colors, but the judge seemed less interested in that.

2. Who Are the Relevant Purchasers of Services from a Law School?

Houston College of Law argued that prospective students are the relevant consumers, while the University of Houston argued for a broader group that includes people who hire law school graduates. Why does this matter?

Let’s back up a little. The key issue in trademark infringement litigation is “likelihood of confusion.” To determine likelihood of confusion, courts consider a list of eight factors (for some reason the Fifth Circuit calls them “digits”), which include the “identity of purchasers” and the “degree of care exercised by potential purchasers.”[3] A higher degree of care means a lower likelihood of confusion.

If, as Houston College of Law argues, the relevant consumers are prospective law school students, you would expect the likelihood of confusion to be lower. These are relatively sophisticated “purchasers” making a major life decision. They are likely to exercise a high degree of care in selecting the place where they are going to spend their lives (and money) for the next three years.

But if you expand the universe of “consumers” to a larger group that includes practicing lawyers and potential clients, you would expect the likelihood of confusion to be higher. In a sense, UH argues, a law school doesn’t just produce education, it produces law school graduates. The “consumers” of those graduates include the people who decide whether to hire the graduates. Those people are not making a life decision about where to go to law school and may be more likely to be confused.

Both arguments are plausible. But arguments are one thing, authorities are another. Judge Ellison asked more than once what authority—meaning case law—the University of Houston had to support its position that the relevant consumers are not just prospective law students. UH had an argument for its broader definition of relevant consumers, but it did not identify any direct authority for it.

But even if the relevant consumers are prospective students, UH argued, the survey conducted by its expert found that the confusion rate among prospective law students was actually higher than the confusion rate among other groups. Houston College of Law, on the other hand, argued that any initial confusion among prospective law students will be quickly dispelled as soon as they start investigating law schools. That argument dovetails with the next legal issue.

3. Does “Initial-Interest Confusion” Matter When the Service at Issue is a Three-Year Law Degree?

When the defendant’s alleged infringement causes initial confusion among consumers that is later cleared up, trademark lawyers call it “initial-interest confusion.” Does evidence of initial-interest confusion establish a “likelihood of confusion”?

Houston College of Law argued that the concept of initial-interest confusion, if it applies at all in the Fifth Circuit, is limited to scenarios like bars and fast food restaurants. For example, if a restaurant on the highway uses the name “McDonalds” to get people to pull over and come in, it has caused McDonalds harm because once those people are “in the door,” they may decide to stay even after they realize “this isn’t the real McDonalds.” Similarly, if a bar uses the word “Elvis” in its name to get people in the door, it has benefitted from the association with the King, even if people later realize that the bar is not affiliated with the real Elvis Presley.[4]

Prospective law school students, on the other hand, are not going to walk into a law school because of the name and say “well, as long as I’m here, I might as well stay another three years and get a law degree.” Even if a prospective student initially thinks that Houston College of Law is affiliated with the University of Houston, that initial impression does not cause any harm to the University of Houston once the student learns he was mistaken. At least that is Houston College of Law’s argument on “initial-interest confusion.”

*Update: On September 13 Judge Ellison issued this order asking for supplemental briefing on this very issue. UH filed this brief on September 20, and Houston College of Law filed this brief on September 27.

4. Does Trademark Infringement Create a Presumption of Irreparable Injury?

If the judge finds a likelihood of confusion, does UH get an injunction? Theoretically, a plaintiff seeking an injunction must show imminent “irreparable injury,” meaning injury that cannot be adequately compensated by money damages. I say “theoretically” because as a practical matter, this is one of the most ignored rules in litigation. The real rule seems to be that an injunction will be issued if the judge thinks the defendant’s conduct is not just bad, but really bad.

But that’s a subject for another post. In trademark litigation, it is usually enough for a plaintiff to prove that the defendant is infringing the plaintiff’s trademark. The court then issues an injunction ordering the defendant to stop doing the thing that is infringing the plaintiff’s trademark. This has become so commonplace that some say a showing of likelihood of confusion creates a presumption of irreparable injury, such that specific evidence of irreparable injury is not required.

However, in eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., the U.S. Supreme Court declined to adopt a categorical presumption that patent infringement causes irreparable harm favoring an injunction.[5]

Does the eBay principle apply to trademark infringement as well? This is an issue trademark lawyers love to argue, but it borders on academic. In most cases the plaintiff offers at least some evidence of irreparable harm. If the judge is inclined to grant an injunction, it is safer for the judge to cite evidence than to rely on a categorical presumption that may or may not apply.

The argument to Judge Ellison on this issue was typical. Houston College of Law argued that there is no presumption of irreparable injury and that the evidence did not prove irreparable injury. Conversely, the University of Houston argued that there is a presumption of irreparable injury and that even without a presumption, the evidence proves irreparable injury.

“How do you value a law school?” UH’s counsel pointedly asked in his summation. If the University of Houston Law Center’s national ranking drops because of confusion with Houston College of Law, he argued, that harm cannot be adequately compensated with dollars. The same number of students may enroll and pay the same tuition, but the quality of the students won’t be the same.

If Judge Ellison issues an injunction [narrator: he did], I expect he will say something to this effect: “It is unclear in the Fifth Circuit whether a showing of trademark infringement creates a presumption of irreparable harm, but in this case it is unnecessary to decide that issue because there is evidence of irreparable harm.”

Will he issue an injunction? Stay tuned to Five Minute Law to find out.

_____________________________

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation (and sometimes even trademark litigation) at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas Super Lawyer® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

His references to arguments made in the lawsuit are not endorsements of the arguments. Any opinions expressed are his own, not the opinions of his firm or clients. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.

[1] Bd. of Regents of the Univ. of Houston Sys. v. Houston College of Law, Inc., No. 4:16-cv-01839 (S.D. Tex. 2016).

[2] Florida Int’l Univ. Bd. of Trustees v. Florida Nat. Univ., Inc., No. 15-11509, 2016 WL 4010164 (11th Cir. July 26, 2016).

[3] Am. Rice, Inc. v. Producers Rice Mill, Inc., 518 F.3d 321, 329 (5th Cir. 2008).

[4] This was an actual case: Elvis Presley Enterprises, Inc. v. Capece, 141 F.3d 188 (5th Cir. 1998).

[5] eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388, 393-94 (2006).

Comments:

This was a very informative post Zach. I’m assuming that the motion for preliminary injunction was denied. Have there been any other updates in the litigation?

Thanks! As of September 15, the judge has not ruled. After the hearing the parties filed additional evidence. On September 13 the judge asked for supplemental briefing on initial-interest confusion (see update above).

If the two parties have their own law school graduates as their counsel, whoever comes out on the losing end may be the one suffering irreparable harm in the future.

I really enjoy these postings! Missed my true calling!

Glad you like them!

Interesting analysis.

jvb

Thanks!

This is excellent!

Thanks, Chelsie. Glad you liked it.